President Barack Obama has remained resolute in his plan to unilaterally reshape U.S. immigration law in the wake of his party’s heavy losses in last week’s midterm elections, but pressure is mounting from both sides as he approaches a decision later this year.

The White House has been tight-lipped about when Obama will use his executive authority on immigration, as well as what exactly the package of reforms will contain. But immigration activists say they still expect the President to issue orders that would protect up to several million undocumented immigrants from deportation. The move could come in mid-December, after lawmakers reach a spending agreement that would keep the federal government running, activists say.

The Democratic drubbing on Nov. 4 unleashed a fresh wave of threats from Republicans, who warned Obama that taking unilateral action on immigration would “poison the well,” as House Speaker John Boehner put it. “When you play with matches, you take the risk of burning yourself,” Boehner cautioned at a post-election press conference last week. “And he’s going to burn himself if he continues to go down this path.”

But Obama has shown no signs of heeding the advice. On multiple occasions since the election, he has vowed to stay the course. “I’m going to do what I can do through executive action,” Obama said Sunday on CBS’ Face the Nation.

Obama’s determination has heartened some immigration advocates, who reacted angrily when the President made the political calculation to postpone the move until after the midterms. “It just seems like Obama, contra to the reputation he’s picked up of going all wobbly when things get intense, is ready to go forward,” says Frank Sharry, executive director of the pro-reform group America’s Voice. “People wouldn’t expect Obama to respond to the election by closing his fist and taking some swings, but that seems to be what he’s doing.”

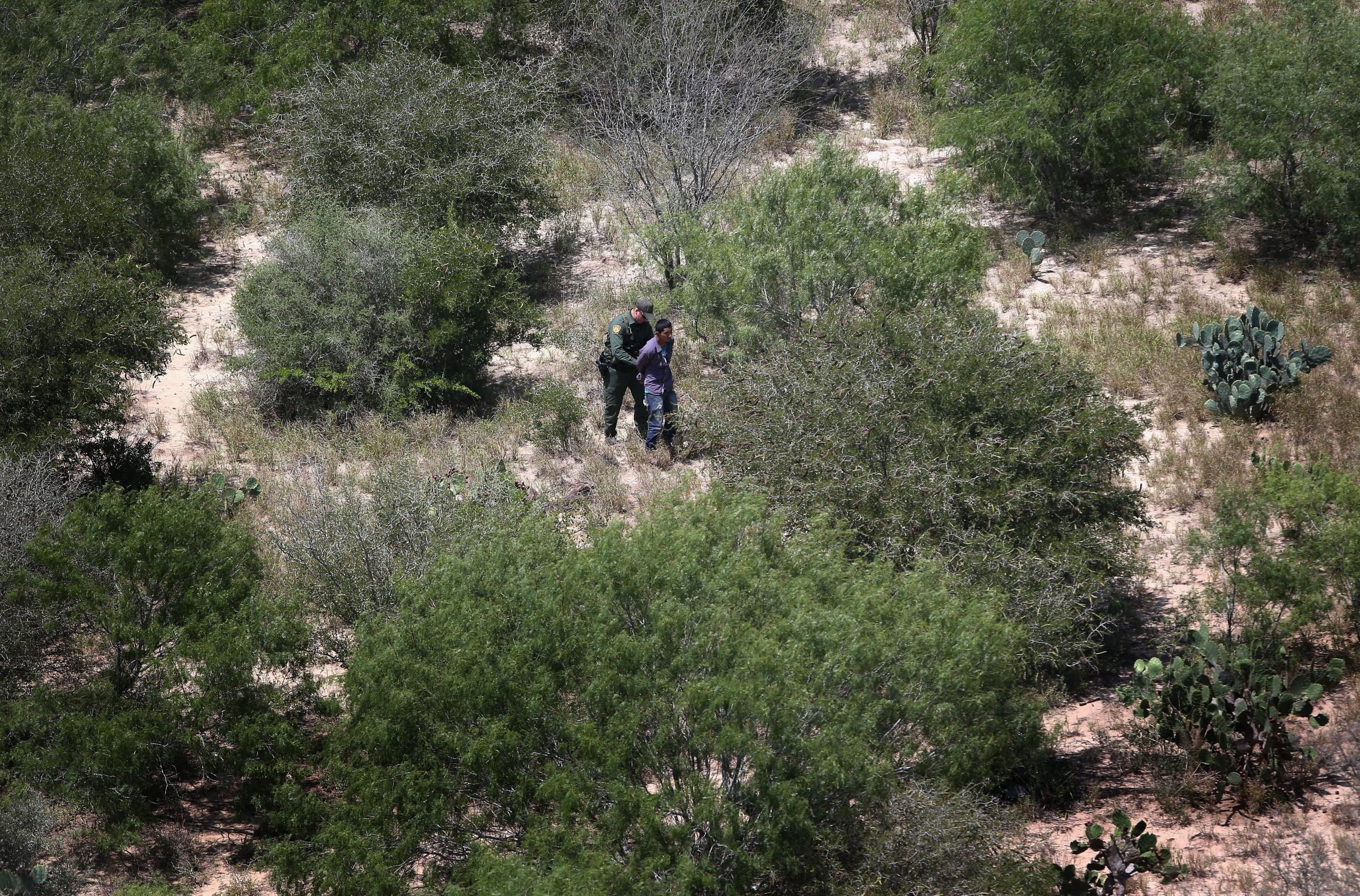

Photographer Captures Birds-Eye View of Border Crisis

The pressure on Obama to delay executive action is likely to build. Republican leaders say that skirting Congress to go it alone would ignite a controversy that jeopardizes the chances for cooperation between the President and the new GOP Congressional majority on a host of issues. “It’s like waving a red flag in front of a bull,” Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell said. Immigration will be a touchstone in confirmation hearings for Loretta Lynch, Obama’s pick for attorney general. Tea Party conservatives in the Senate signaled they plan to use the hearings to press Lynch on her views of the President’s executive authority on immigration.

Enacting sweeping changes to immigration law just weeks after the party was rebuked by voters at the polls could spark a blowback from voters. In one recent survey, conducted by Republican pollster Kellyanne Conway, 74% of respondents said they preferred Obama to work with Congress to retool a broken immigration system rather than maneuvering around the legislative branch.

Even some seasoned Democrats seem a bit skittish about the idea. Over a sea bass lunch Friday with Congressional leaders in the Old Family Dining Room of the White House, Obama told Boehner that his patience in waiting for the House to act on immigration had run out. At that point, according to a source familiar with the meeting, Vice President Joe Biden piped up to ask how long Republicans would need to craft immigration legislation—prompting the President to shoot Biden a look that closed the discussion.

Ed Rendell, the former Pennsylvania governor and erstwhile head of the Democratic National Committee, told reporters last week that one way to avoid inflaming Obama’s antagonists was for the President to publicly outline the terms of the immigration order in the coming weeks, but wait until “April or June” to issue it, giving the GOP time to cobble together a bill.

Many Republicans are eager to address immigration in order to help repair their relationship with Hispanic voters, who will once again play a key role in the 2016 presidential election. But “it is not going to be at the top of the list” for the new Republican majority, acknowledged former Mississippi governor and Republican National Committee chair Haley Barbour, a supporter of immigration reform, on a conference call arranged by the Bipartisan Policy Center. Indeed, there is no evidence that the prevailing GOP opposition to comprehensive immigration reform in the House—and especially on a path to citizenship, about which Democrats are insistent—has softened.

It would take about six months for Administration officials to implement orders that could include work authorization and protections from deportation for three or four million people, along with changes to programs such as Secure Communities, a Department of Homeland Security program introduced under President George W. Bush that dictates how immigration officials enforce the law.

Such a move would mark a dramatic shift for a President who was careful not to inject himself into lengthy partisan wrangling over legislative specifics, then made a futile attempt to protect embattled Democrats this fall by sidestepping a political fight. This time he seems ready to pick one. “He waited until after the election to try to take it out of the political milieu,” Rendell said. “But he’s gotta do it.”

With reporting by Zeke J. Miller

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com