Military service was a tradition in the families who joined the Army Reserve’s 14th Quartermaster Detachment. They came from communities and circumstances that yield more volunteers for the military than do other parts of our society. They lived in a part of Pennsylvania where so many young people were in the military that “whenever a disaster happens anywhere in the world,” a local reporter observed, “people around here hold their breath.” They were likely to know some of the casualties in the February 25, 1991, Scud missle attack in Saudi Arabia that killed 28 reservists.

Specialist Beverly Sue Clark, 23, was from Indiana County, Pennsylvania. She had joined the Reserves out of high school. She worked as a security guard and as a secretary at a local window and door manufacturer. She wanted to be a teacher. She was popular and athletic and loved to ski. Her best friend in the 14th Quartermaster Detachment, headquartered in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, was Mary Rhoads, a meter maid in California Borough, Pennsylvania. Mary joined the Army Reserve in 1974, during the summer between her junior and senior years at Canon-McMillan Senior High, south of Pittsburgh. She didn’t have clear plans for her life after graduation, and she thought a part-time job in the army would let her follow in the family tradition and bring home much needed extra income.

In 1979 she transferred from the engineering company to the 1004th General Supply Company, also based at the Army Reserve Center in Greensburg. Mary and Beverly became friends when Beverly joined the 1004th in 1985. They hit it off right away. Mary, ten years in the Reserves by then, took the younger woman under her wing. When Mary transferred to the 14th Quartermaster Detachment at Greensburg in 1988, Bev followed her. They were close, and thought they always would be. They would watch each other’s kids grow up. Mary’s daughter, Samantha, called Beverly “Aunt Bev” and always pestered Mary to pass the phone to Beverly when she called home.

Predictions varied about how many dead and wounded the United States would suffer in the war. Most were wildly off the mark. The U.S. Armed Forces were immeasurably better war fighters, better armed and equipped, and better led than the armed forces of the Republic of Iraq. None of the prognosticators realized just how much of a war you could fight from the air over a desert battleground where the enemy parked his tanks and artillery in the glaring sun and sheltered his soldiers in sand berms. Nor did they appreciate just how determined Desert Storm’s commander, General H. Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., was to use the immense force he assembled to keep casualties low.

Given the nature of the war—a long air campaign followed by a short ground war and Iraq’s quick capitulation—casualties were far fewer than the most optimistic analyst had expected. But there were casualties: 149 killed in action, a comparable number of noncombat deaths, and eight hundred or so wounded. Three hundred graves over which three hundred families wept and prayed. Many thousands of survivors wept too and bore their own wounds, seen and unseen. It helps none of them to know it could have been worse.

***

In January President Bush authorized the call-up of one million reservists and national guardsmen for up to two years. The sixty-nine soldiers of the 14th Quartermaster Detachment had started hearing scuttlebutt back in November that they would eventually deploy to the Gulf. Their order to mobilize came on January 15, 1991, the day before Desert Storm commenced. They left for Saudi Arabia on February 18 and arrived at the air base the next day. They were quartered temporarily in a large corrugated metal warehouse in Al Khobar, a suburb several miles from Dhahran.

Of course, they wouldn’t be on the front lines, although to do their jobs they would have to be closer than two hundred miles behind the front in Al Khobar. Some soldiers had premonitions, as soldiers off to war often do. Beverly Clark told her friend Mary Rhoads she had a bad feeling about the whole thing. She also mentioned her apprehension in the journal she kept. Soldiers’ families have premonitions too, especially the mothers. Just before she passed away from pancreatic cancer in November, Rhoads’s mother had told her that something terrible would happen but that Rhoads would be okay. Whatever fears disturbed them, none of the reservists resented their call-up.

Eleven of the reservists in the 14th who deployed to Saudi Arabia were women. The Persian Gulf War occasioned the largest single deployment of women to a combat zone in American military history. Forty-one thousand officers and enlisted—one out of every five women in uniform—deployed. They were pilots, aircrew, doctors, dentists, nurses, military police, truck drivers, communications technicians, intelligence analysts, security experts, administrative clerks, and water purification specialists deployed to a society built on tribalism, Islamic fundamentalism, and primitive notions of gender inequality. Thirteen of them would be killed, four from enemy fire. Twenty-one were wounded in action and two taken prisoner. They did just about everything the men did, including flying missions and accepting other assignments that blurred the lines separating women from combat roles. But this was a war where lines were readily blurred. Even the idea of a front line seemed an anachronism in a war where so much of the fighting was in the air and where missiles were fired at targets located far to the rear, even at a country that wasn’t a belligerent. The metaphor “a line in the sand” has come to mean a statement of resolve, but it originally indicated something impermanent, something that disappears in the first breeze. That is an apt metaphor for the Persian Gulf War, where the front was, literally and figuratively, a line in the sand. Even two hundred miles in the rear, the front could suddenly encompass you.

For people of an active disposition, the Gulf War, irrespective of its high-tech thrills, its stunning successes and surprising brevity, could have been stultifying to soldiers who weren’t involved in the fighting. Mary Rhoads was bored to tears sitting in that big warehouse, and she hated being bored. She had spent seventeen years in the Army Reserve, half her life. She looked at the kids in the unit as her kids, saw herself as the mother hen. She picked up stuff they liked to eat, things to read, games to play, anything that might shorten the days until they were sent forward to do the job they had come to do. She had purchased a Trivial Pursuit game, among other diversions, and it was instantly a favorite entertainment in the barracks. She still felt closest to Clark. They both brought teddy bears with them to war; Clark’s was white and Rhoads’s brown. One night they were both on guard duty on the warehouse roof when Bev noticed a mist forming in the desert. “Look,” she pointed, “the angel of death.” Rhoads would remember that through all the years that followed, wondering if her friend had had another premonition.

***

The Iraqis fired four Scuds the night of February 25. Three of them appeared to break up in the atmosphere. The missile fired at 8:32 p.m. was detected by satellite and its position relayed to Patriot crews in Saudi Arabia. Three batteries tracked it on their radarscopes but didn’t launch their missiles because the Scud was outside their respective sectors. Two batteries, Alpha and Bravo, protected the air base at Dhahran. Bravo was shut down for maintenance that night. Alpha’s crew had been alerted to the Scud traveling in their direction, but their screen was blank. They checked to make sure their equipment was operating properly and were satisfied that it was. Still they saw nothing. They didn’t know their range gate had miscalculated the missile’s whereabouts. No one knew a Scud was plunging to earth at five times the speed of sound above the big metal warehouse where 127 reservists were living.

Ten minutes later, driving down the highway toward Dhahran, Rhoads heard the siren. They pulled off the road and watched as the Scud slammed into the barracks and detonated, creating a red and orange inferno that engulfed twisted beams, flying shrapnel, the modest possessions and mementos of the dead, and their charred bodies. Twenty-eight people were killed and ninety-nine wounded, grievously wounded in many cases. Among the dead were thirteen reservists in the 14th Quartermaster Detachment, including Clark. Forty-three of the reservists wounded in the attack were from the 14th, which meant the detachment had suffered in a single attack a casualty rate higher than 80 percent, about as high a rate as any recorded. They had been in Saudi Arabia only six days.

Rhoads and her companions raced back to the base. They had to climb a fence to get into the compound, where all was bedlam. Fire trucks and ambulances had raced to the scene, sirens wailing. Blackhawks descended from the dark heavens to airlift the most seriously wounded. Rhoads tried to enter the burning building, but one of the rescuers stopped her. “My friends are in there,” she repeated over and over again. “You don’t want to go in there,” he warned her. When the ambulances pulled away, she ran to the other side and entered the building there. The smell of burned flesh, of death, filled her nostrils. She thought they were all dead. A moment later she tripped over a girder, wrenching her knee. A soldier in a transportation unit pulled her back outside and told her to stay there. That was where she saw the bodies. The Vietnam veterans in the unit who survived the attack had retrieved them and lined them up side by side. She recognized Clark right away. She limped over to her friend, embraced her lifeless form, and shrieked at the treacherous night, while a news camera recorded her agony.

Everyone who wasn’t badly hurt was quartered that night in a large, convention center–like meeting space, where television sets replayed the disaster on what seemed a continuous loop. Rhoads called her husband to let him know she was alive and reported to a sergeant back at the Reserve center in Greensburg. Then she and a few others, impatient and wanting to help, commandeered a van and drove first to the warehouse, then to different hospitals to locate the wounded, and then to the morgue to identify the dead. Rhoads identified the bodies of Tony Madison, Frank Keough, and Beverly Clark.

***

Rhoads eventually returned to her job with her leg in a big white brace. She was eager to get going; she wanted her life back. Something was wrong, though. She had frequent nightmares; she lost her temper. She used to shrug off the kids who hassled her and called her names for giving them a parking ticket; now she got into it with them, right in their faces, daring them. She wasn’t herself. She froze once while directing traffic when she heard an emergency vehicle’s siren. Then she started getting really sick.

Chronic vaginal bleeding resulted in a hysterectomy. She had her gall bladder removed and her appendix. Stomach ailments, headaches, sinus troubles, and serious difficulty breathing brought her to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, then the hospital in Brownsville, Pennsylvania, the VA hospital in Pittsburgh, then back to Walter Reed and again to Pittsburgh. Doctors discovered precancerous cells in her esophagus. She developed liver disease.

These and other ailments were attributed to the mysterious malady that afflicted many Desert Storm veterans, called Persian Gulf War syndrome. None of the doctors Rhoads saw in Bethesda or Pittsburgh could figure out what was making her so sick. She was becoming almost completely incapacitated. Scott Beveridge and another local reporter, Connie Gore, took a genuine interest in her case and wrote about her often. Her local congressman, Frank Mascara, and his aide, Pam Snyder, got involved and pushed the VA to recognize that whatever its cause, Gulf War syndrome was real, and it was destroying the lives of people who had risked everything to serve their country and who deserved their government’s attention to their service-related illness. Their persistent appeals on her behalf resulted in a full disability pension, one of the first awarded to a sufferer of Gulf War syndrome. She gave testimony to the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee in 1991 and traveled to Washington in 1995, while very ill, to testify to President Bill Clinton’s Advisory Commission on Gulf War Illnesses. Congressman Mascara began his statement in a hearing at the House Veterans Committee by invoking her as the poster child for Gulf War syndrome.

When word got around about his successful intervention on Rhoads’s behalf, Mascara’s office was swarmed with calls from veterans around the country, who like Rhoads were plagued by numerous illnesses since coming home from the Gulf. No one has yet to establish a cause or causes of the disorder that appears to weaken the immune system, making its victims susceptible to multiple illnesses. There are many theories—fumes from the oil well fires, reactions to inoculations, Iraq’s undetected use of chemical weapons, Scud warheads carrying biological agents, combat stress—but none have been proven. Whatever its cause, thousands of Gulf War veterans suffer chronic and multiple illnesses attributed to it.

After her testimony to President Clinton’s advisory commission, Rhoads dropped out of public view. Beveridge wrote that he had received “anonymous hate mail” attacking Rhoads for publicizing her suffering and condemning the deployment of women to war theaters. It appears she heard some of the same criticism. She might have been estranged, for a brief time anyway, from a few others in her unit. When asked, she said the 14th was like a family, and like all families, they have their squabbles and then make up. “We love each other,” she maintains.

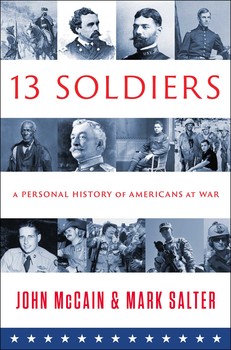

Senator John McCain is a United States Senator and an author, with Mark Salter, of Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History of Americans at War, out today. He served in the U.S. Navy from 1954 until 1981.

Mark Salter is the author, with John McCain, of several books, including Faith of My Fathers. He served on Sen. McCain’s staff for 18 years.

From Thirteen Soldiers: A Personal History of Americans at War, by John McCain and Mark Salter. Copyright © 2014 by John McCain and Mark Salter. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com