“I knew this work was going to be darker,” says the visual artist Doug Rickard. “As I started to dive into the footage, I realized that there was an extra motive for posting videos on YouTube, and often it was a rather dark motive in itself.”

In 2012, Rickard presented his take on the American landscape using Google Street View. Now, he is sifting through the massive online video cache to reveal, in still frames, the things that go unnoticed among the ubiquity of virtual imagery.

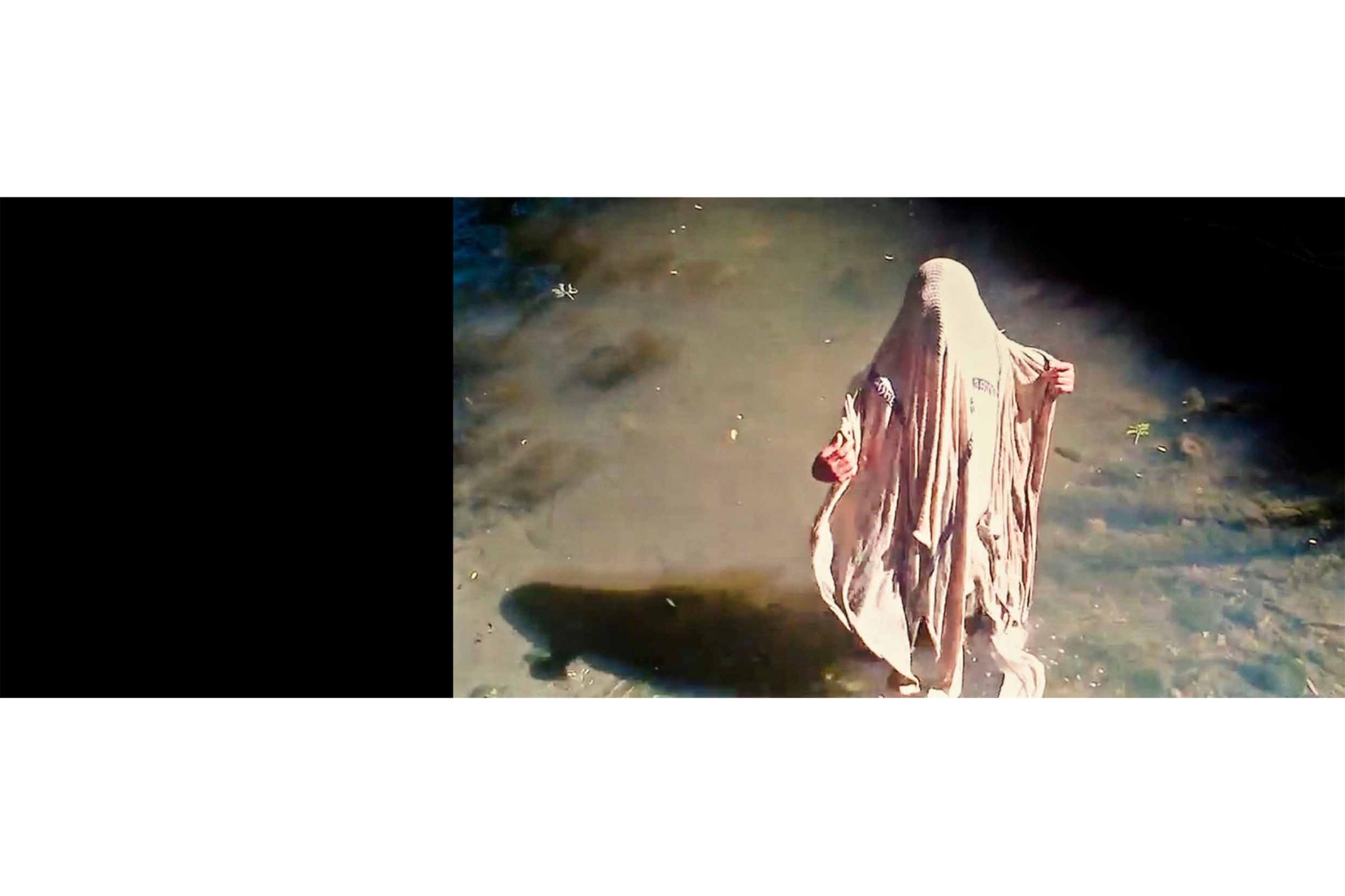

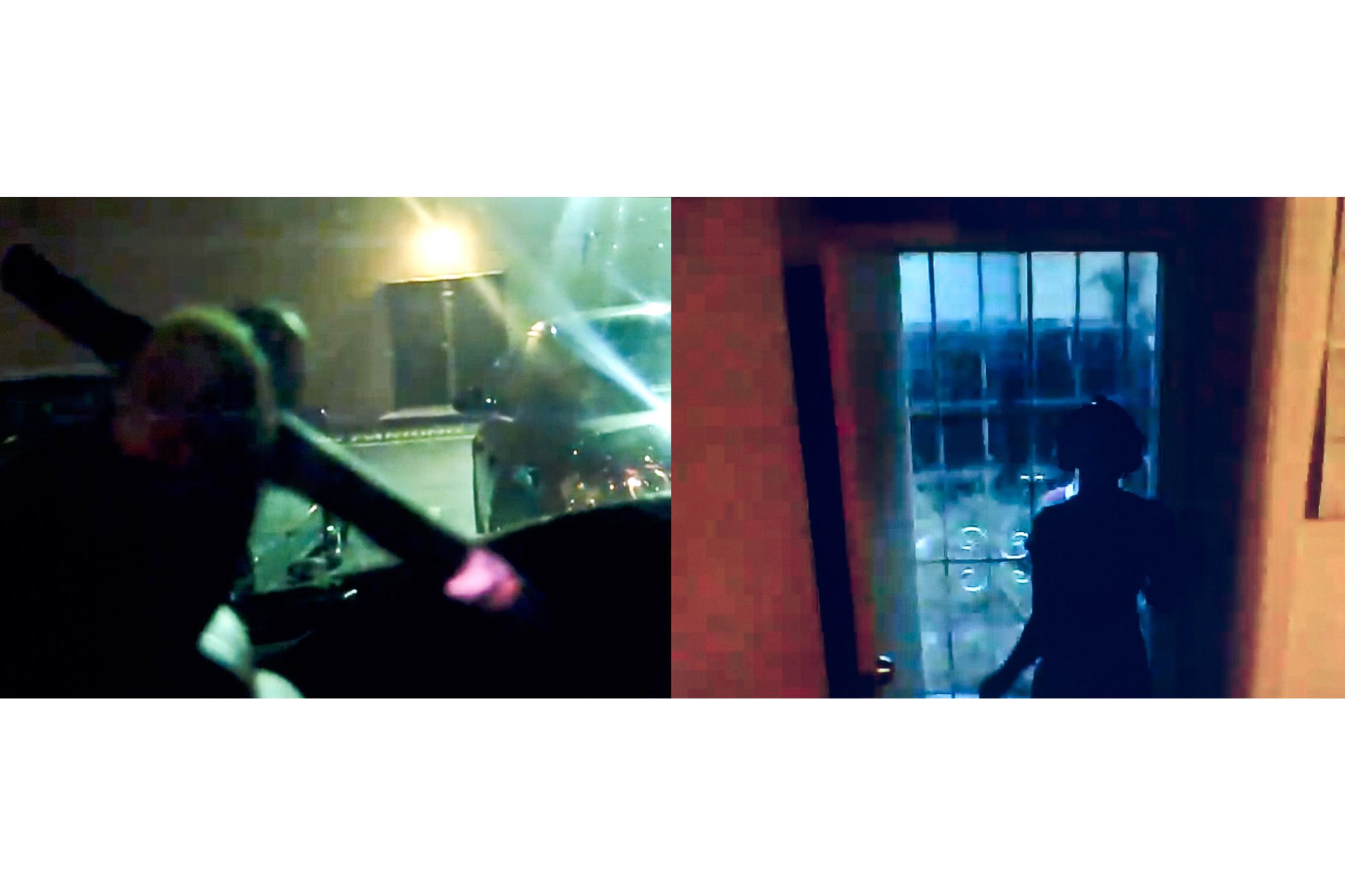

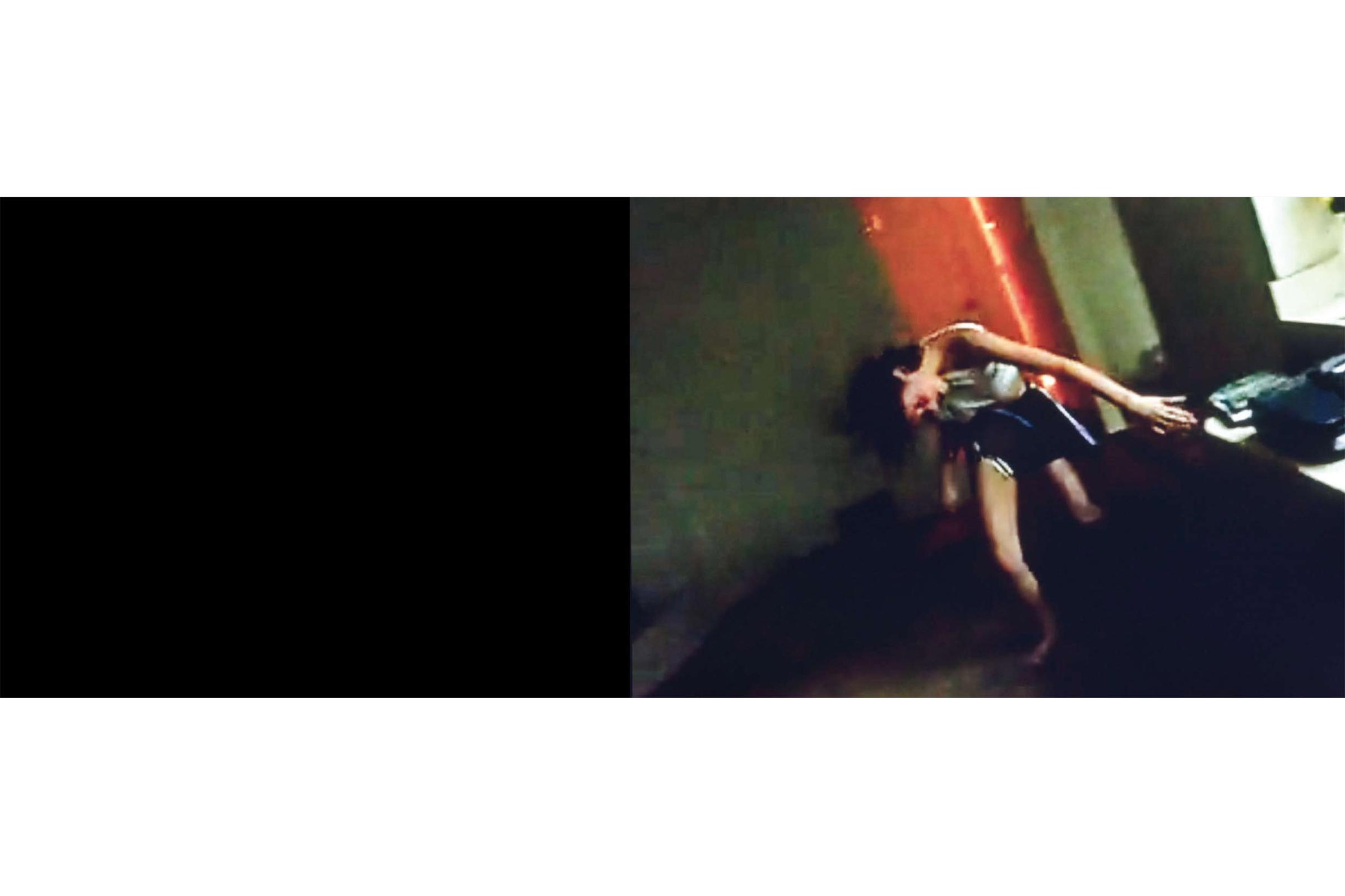

In Rickard’s work, the media is central to the message, though his final product, whether it’s a print, a photo book or a video installation, is helplessly alone, removed from any identifying context that could concretely explain what we’re seeing. What is clear from NA, his latest project, is that digital imagery, whether in video or still form, is loaded with interactive tension.

Clicks, likes and views are encouraging people to exploit each other online, Rickard suggests, as the line between public and private becomes increasingly blurred in a confusing and caustic digital landscape. “I think the technology is embedding a new dynamic that is voyeuristic in terms of the audience and their appetite for voyeurism, and also predatory, in terms of why people are posting photos or videos and what their motivations are,” he says.

Rickard, who describes himself as an artist working with digital technologies, has faced a fair amount of push back for his work, as photography purists take issue with his appropriation of images. His actual process of creating images, however, presents a counter argument. For both New American Pictures, his street view project, and NA, Rickard sets up a digital camera on a tripod in front of a dedicated screen that mirrors a second screen that he uses to navigate. He then performs exhaustive keyword searches and scans the results, and with a shutter release cable in his left hand and a mouse in his right, selects a broad swath of material to work from. From there, he says the most crucial and aesthetically critical part of his process begins: editing.

“I’m stitching together what I feel is a vision that’s cohesive, and yet has elements that are distinct; elements that are connected,” he says. “It’s a whole dance of moving parts that have to do with color and light and shadow – all the elements that traditional photography deals with – so I would get to a point where I could look at thumbnails on a screen as I’m going through search categories and recognize before I view the video if the lighting, or the color was going to work out.”

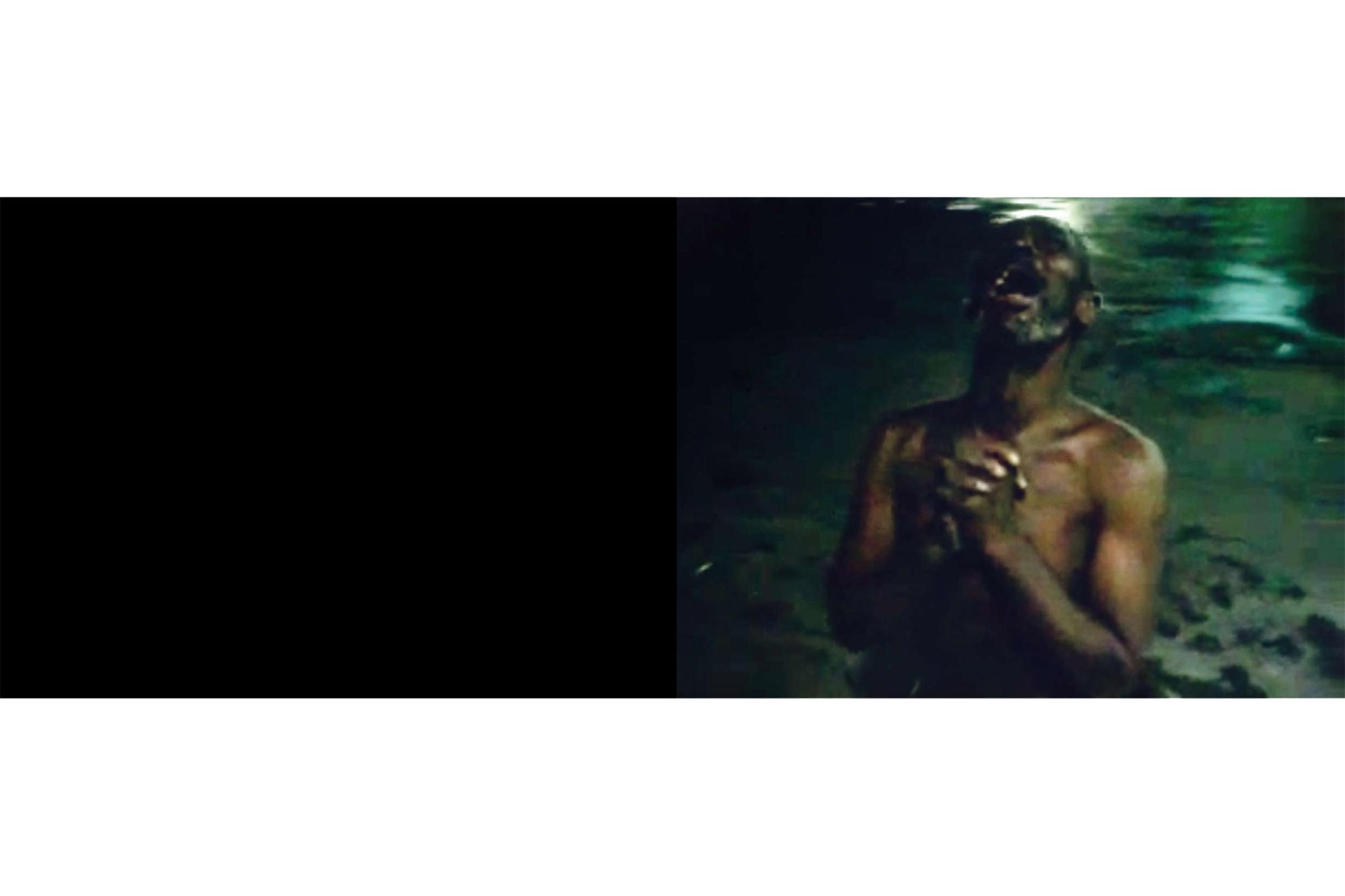

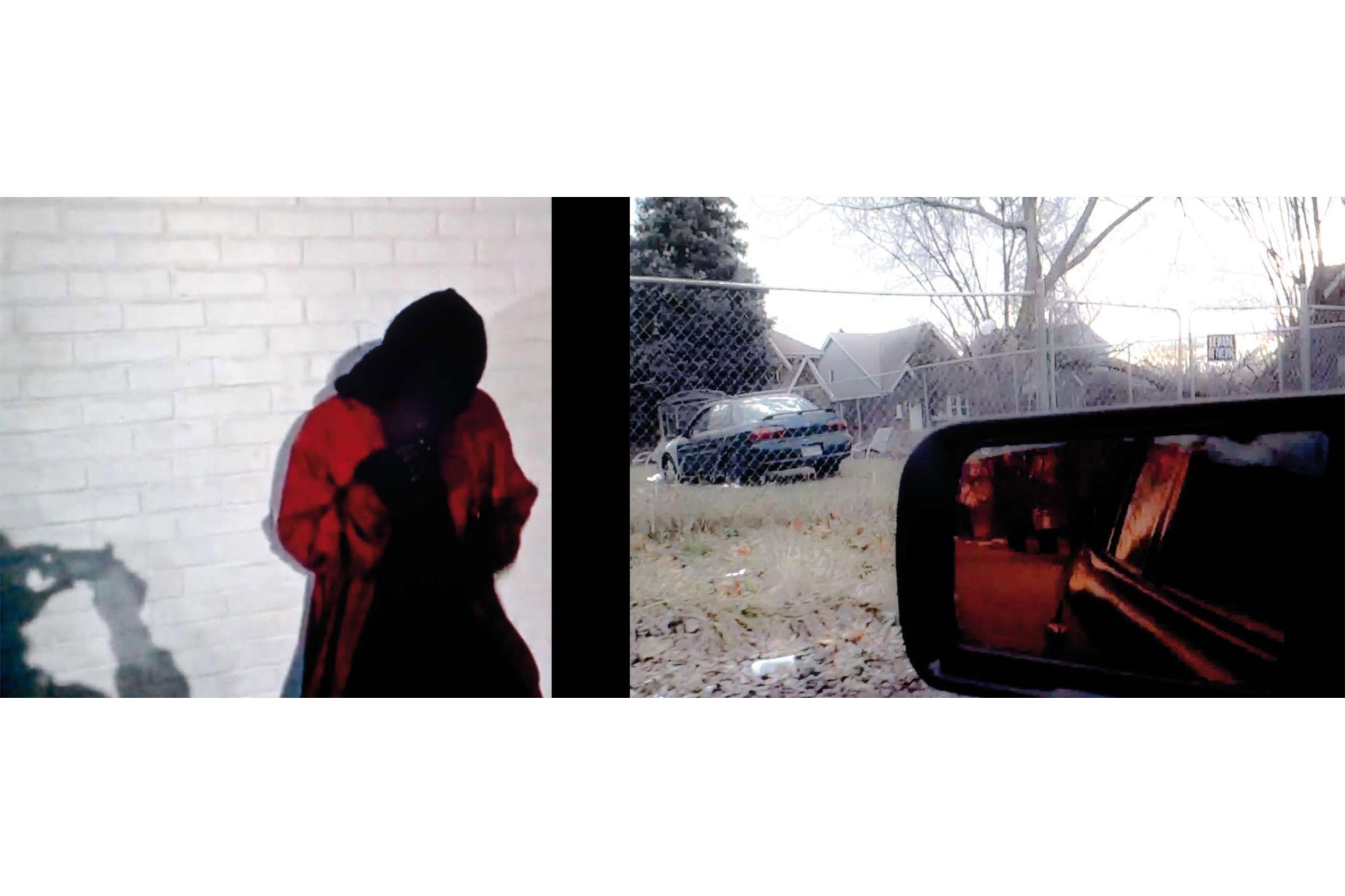

That same sense of stitched-togetherness translates to the physical pages of the book, which is laid out in an off kilter, almost disorienting way. Images are separated at times by varying blocks of black space, spread unevenly across one or two pages, while others are pushed uncomfortably close together, barely split by the seam of the book, emphasizing the uneasy viewing experience Rickard says he intentionally subjects his audience to.

“I’m not satisfied anymore with the most simple or visually pleasing of layouts,” Rickard says. “You need interruptions of sorts and take things out of perfect symmetry in order to carry the ark of a book through and prevent complacency on the part of the viewer. There’s an intent to mix that up.”

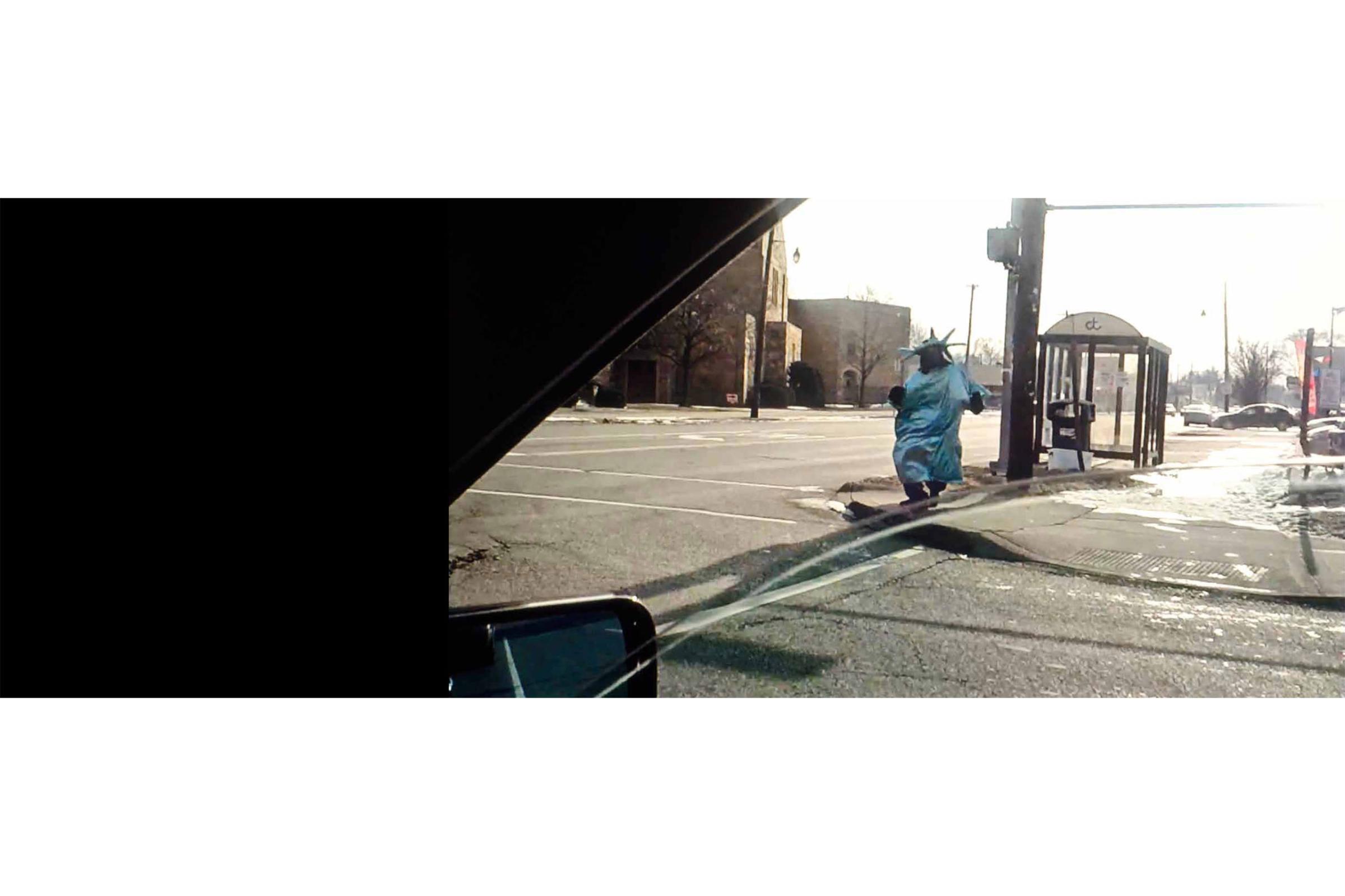

The physical layout of the book is part of Rickard’s larger mission to embed deep layers of subtext into his projects, both by completely removing his source material from its native platform and format, but also by choosing to show images that he sees as socially, politically and historically loaded. His aesthetic cynicism is most often aimed at America, questioning in images the various ways American ideals and values are distorted.

“I’m so focused on the idea of America and the idea of what we present, and then a different idea of the way things may really be, and what we present in terms of American history as opposed to the way that history actually went down,” he says. “There are constant gaps between the way we want to see ourselves, the way we think other nations see us, and then the way we actually are. I can’t get off of that.”

And perhaps there’s no reason to. Visual imagery uploaded online is transient at best, but for Rickard, they illustrate larger, darker issues of racism, class inequality and hypocrisy. As images continue to fall haphazardly into the ethers of the internet, Rickard is sifting through them, pulling from our collective virtual consciousness the angst, irony and at times outright aggressiveness we exhibit on quasi-public online forums, but prefer to ignore in the real world.

Doug Rickard is a multimedia artist based in California. His new book NA will be published in December, 2014 by DAP.

Krystal Grow is a contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @kgreyscale

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com