You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

For 28 years it had stood as the symbol of the division of Europe and the world, of Communist suppression, of the xenophobia of a regime that had to lock its people in lest they be tempted by another, freer life — the Berlin Wall, that hideous, 28-mile-long scar through the heart of a once proud European capital, not to mention the soul of a people. And then — poof! — it was gone. Not physically, at least yet, but gone as an effective barrier between East and West, opened in one unthinkable, stunning stroke to people it had kept apart for more than a generation. It was one of those rare times when the tectonic plates of history shift beneath men’s feet, and nothing after is quite the same.

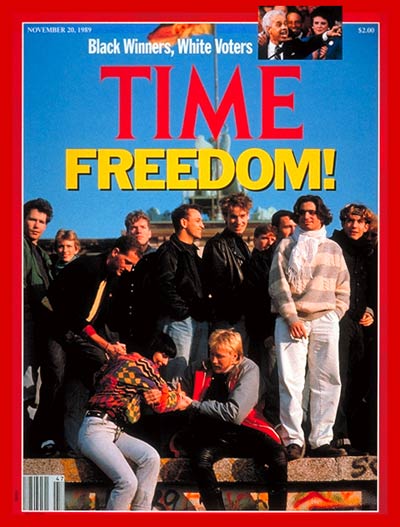

What happened in Berlin last week was a combination of the fall of the Bastille and a New Year’s Eve blowout, of revolution and celebration. At the stroke of midnight on Nov. 9, a date that not only Germans would remember, thousands who had gathered on both sides of the Wall let out a roar and started going through it, as well as up and over. West Berliners pulled East Berliners to the top of the barrier along which in years past many an East German had been shot while trying to escape; at times the Wall almost disappeared beneath waves of humanity. They tooted trumpets and danced on the top. They brought out hammers and chisels and whacked away at the hated symbol of imprisonment, knocking loose chunks of concrete and waving them triumphantly before television cameras. They spilled out into the streets of West Berlin for a champagne-spraying, horn-honking bash that continued well past dawn, into the following day and then another dawn. As the daily BZ would headline: BERLIN IS BERLIN AGAIN.

Nor was the Wall the only thing to come tumbling down. Many who served the regime that had built the barrier dropped from power last week. Both East Germany’s Cabinet and the Communist Party Politburo resigned en masse, to be replaced by bodies in which reformers mingled with hard-liners. And that, supposedly, was only the start. On the same day that East Germany threw open its borders, Egon Krenz, 52, President and party leader, promised “free, general, democratic and secret elections,” though there was no official word as to when. Could the Socialist Unity Party, as the Communists call themselves in East Germany, lose in such balloting? “Theoretically,” replied Gunter Schabowski, the East Berlin party boss and a Politburo member.

Thus East Germany probably can be added, along with Poland and Hungary, to the list of East European states that are trying to abandon orthodox Communism for some as-yet-nebulous form of social democracy. The next to be engulfed by the tides of change appears to be Bulgaria; Todor Zhivkov, 78, its longtime, hard-line boss, unexpectedly resigned at week’s end. Outlining the urgent need for “restructuring,” his successor, Petar Mladenov, said, “This implies complex and far from foreseeable processes. But there is no alternative.” In all of what used to be called the Soviet bloc, Zhivkov’s departure leaves in power only Nicolae Ceausescu in Rumania and Milos Jakes in Czechoslovakia, both old-style Communist dictators. Their fate? Who knows? Only a few weeks ago, East Germany seemed one of the most stolidly Stalinist of all Moscow’s allies and the one least likely to undergo swift, dramatic change.

The collapse of the old regimes and the astonishing changes under way in the Soviet Union open prospects for a Europe of cooperation in which the Iron Curtain disappears, people and goods move freely across frontiers, NATO and the Warsaw Pact evolve from military powerhouses into merely formal alliances, and the threat of war steadily fades. They also raise the question of German reunification, an issue for which politicians in the West or, for that matter, Moscow have yet to formulate strategies. Finally, should protest get out of hand, there is the risk of dissolution into chaos, sooner or later necessitating a crackdown and, possibly, a painful turn back to authoritarianism.

In East Germany the situation came close to spinning out of control. Considered a hard-liner, Krenz succeeded the dour Erich Honecker as party chief only three weeks ago, and eleven days after a state visit by Mikhail Gorbachev. Ever since, Krenz has had to scramble to find concessions that might quiet public turmoil and enable him to hang on to at least a remnant of power. He has been spurred by a series of mass protests — one demonstration in Leipzig drew some 500,000 East Germans — demanding democracy and freedoms small and large, and by a fresh wave of flight to the West by many of East Germany’s most productive citizens. So far this year, some 225,000 East Germans out of a population of 16 million have voted with their feet, pouring into West Germany through Hungary and Czechoslovakia at rates that last week reached 300 an hour. Most are between the ages of 20 and 40, and their departure has left behind a worsening labor shortage. Last week East German soldiers had to be pressed into civilian duty to keep trams, trains and buses running.

The Wall, of course, was built in August 1961 for the very purpose of stanching an earlier exodus of historic dimensions, and for more than a generation it performed the task with brutal efficiency. Opening it up would have seemed the least likely way to stem the current outflow. But Krenz and his aides were apparently gambling that if East Germans lost the feeling of being walled in, and could get out once in a while to visit friends and relatives in the West or simply look around, they would feel less pressure to flee the first chance they got. Beyond that, opening the Wall provided the strongest possible indication that Krenz meant to introduce freedoms that would make East Germany worth staying in. In both Germanys and around the world, after all, the Wall had become the perfect symbol of oppression. Ronald Reagan in 1987, standing at the Brandenburg Gate with his back to the barrier, was the most recent in a long line of visiting Western leaders who challenged the Communists to level the Wall if they wanted to prove that they were serious about liberalizing their societies. “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!” cried the President. “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” There was no answer from Moscow at the time; only nine months ago, Honecker vowed that the Wall would remain for 100 years.

When the great breach finally came, it started undramatically. At a press conference last Thursday, Schabowski announced almost offhandedly that starting at midnight, East Germans would be free to leave at any point along the country’s borders, including the crossing points through the Wall in Berlin, without special permission, for a few hours, a day or forever. Word spread rapidly through both parts of the divided city, to the 2 million people in the West and the 1.3 million in the East. At Checkpoint Charlie, in West Berlin’s American sector, a crowd gathered well before midnight. Many had piled out of nearby bars, carrying bottles of champagne and beer to celebrate. As the hour drew near, they taunted East German border guards with cries of “Tor Auf!” (Open the gate!).

On the stroke of midnight, East Berliners began coming through, some waving their blue ID cards in the air. West Berliners embraced them, offered them champagne and even handed them deutsche mark notes to finance a celebration (the East German mark, a nonconvertible currency, is almost worthless outside the country). “I just can’t believe it!” exclaimed Angelika Wache, 34, the first visitor to cross at Checkpoint Charlie. “I don’t feel like I’m in prison anymore!” shouted one young man. Torsten Ryl, 24, was one of many who came over just to see what the West was like. “Finally, we can really visit other states instead of just seeing them on television or hearing about them,” he said. “I don’t intend to stay, but we must have the possibility to come over here and go back again.” The crowd erupted in whistles and cheers as a West Berliner handed Ryl a 20-mark bill and told him, “Go have a beer first.”

Many of the visitors pushed on to the Kurfurstendamm, West Berlin’s boulevard of fancy stores, smart cafes and elegant hotels, to see prosperity at first hand. At 3 a.m., the street was a cacophony of honking horns and happily shouting people; at 5 some were still sitting in hotel lobbies, waiting for dawn. One group was finishing off a bottle of champagne in the lobby of the Hotel Am Zoo, chatting noisily. “We’re going back, of course,” said a woman at the table. “But we must wait to see the stores open. We must see that.”

Later in the day, two young workers from an East Berlin electronics factory who drove through Checkpoint Charlie in a battered blue 1967 Skoda provided a hint that Krenz may in fact have scored a masterstroke by relieving some of the pressure to emigrate. Uwe Grebasch, 28, the driver, said he and his companion, Frank Vogel, 28, had considered leaving East Germany for good but decided against it. “We can take it over there as long as we can leave once in a while,” said Grebasch. “Our work is O.K., but they must now let us travel where we want, when we want, with no limits.”

The world has, or thought it had, become accustomed to change in Eastern Europe, where every week brings developments that would have seemed unbelievable a short while earlier. Nonetheless, the opening of the Wall caught it off guard. President George Bush, who summoned reporters into the Oval Office Thursday afternoon, declared himself “very pleased” but seemed oddly subdued. Aides attributed that partly to his natural caution, partly to uncertainty about what the news meant, largely to a desire to do or say nothing that might provoke a crackdown in East Germany. As the President put it, “We’re handling it in a way where we are not trying to give anybody a hard time.” By Friday, though, Bush realized he had badly underplayed a historic event and, in a speech in Texas, waxed more enthusiastic. “I was moved, as you all were, by the pictures,” said Bush. He also got in a plug for his forthcoming meeting with Gorbachev on ships anchored off the coast of Malta: “The process of reform initiated by the East Europeans and supported by Mr. Gorbachev . . . offers us all much hope and deserves encouragement.”

Gorbachev in fact may have done more than merely support the East German opening. It was no coincidence that Honecker resigned shortly after the Soviet President visited East Berlin, and that the pace of reform picked up sharply after Krenz returned from conferring with Gorbachev in Moscow two weeks ago. In pursuing perestroika — in his eyes not to be limited to the U.S.S.R. — and preaching reform, Gorbachev has made it clear that Moscow will tolerate almost any political or economic system among its allies, so long as they remain in the Warsaw Pact and do nothing detrimental to Soviet security interests. The Kremlin greeted the opening of the Wall as “wise” and “positive,” in the words of Foreign Ministry spokesman Gennadi Gerasimov, who said it should help dispel “stereotypes about the Iron Curtain.” But he warned against interpreting the move as a step toward German reunification, which in Moscow’s view could come about only after a dissolution of both NATO and the Warsaw Pact, if at all.

West Germany, the country most immediately and strongly affected, was both overjoyed and stunned. In Bonn members of the Bundestag, some with tears in their eyes, spontaneously rose and sang the national anthem. It was a rare demonstration in a country in which open displays of nationalistic sentiment have been frowned on since the Third Reich died in 1945.

“Developments are now unforeseeable,” said West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who interrupted a six-day official visit to Poland to fly to West Berlin for a celebration. “I have no doubt that unity will eventually be achieved. The wheel of history is turning faster now.” At the square in front of the Schoneberg town hall, where John F. Kennedy had proclaimed in 1963 that “Ich bin ein Berliner,” West Berlin Mayor Walter Momper declared, “The Germans are the happiest people in the world today.” Willy Brandt, who had been mayor when the Wall went up and later, as federal Chancellor, launched a Bonn Ostpolitik that focused on building contacts with the other Germany, proclaimed that “nothing will be the same again. The winds of change blowing through Europe have not avoided East Germany.” Kohl, who drew some boos and whistles as well as cheers, repeated his offer to extend major financial and economic aid to East Germany if it carried through on its pledges to permit a free press and free elections. “We are ready to help you rebuild your country,” said Kohl. “You are not alone.”

Running through the joy in West Germany, however, was a not-so-subtle undertone of anxiety. Suppose the crumbling of the Wall increases rather than reduces the flood of permanent refugees? West Germany’s resources are being strained in absorbing, so far this year, the 225,000 immigrants from East Germany, as well as 300,000 other ethnic Germans who have flocked in from the Soviet Union and Poland. According to earlier estimates, up to 1.8 million East Germans, or around 10% of the population, might flee to the West if the borders were opened — as they were last week all along East Germany’s periphery. (Within 48 hours of the opening of the Wall, nearly 2 million East Germans had crossed over to visit the West; at one frontier post, a 30-mile- long line of cars was backed up.) West Germans fear they simply could not handle so enormous a population shift.

Thus West German leaders’ advice to their compatriots from the East was an odd amalgam: We love you, and if you come, we will welcome you with open arms — but really, we wish you would stay home. “Anyone who wants can come,” said Mayor Momper, but added, “Please, even with all the understandable joy you must feel being able to come to the West, please do it tomorrow, do it the day after tomorrow. We are having trouble dealing with this.” In Bonn, Interior Minister Wolfgang Schauble warned would-be refugees that with a cold winter coming on, the country is short of housing. Hannover Mayor Herbert Schmalstieg, who is also vice president of the German Urban Council, called for legal limits on the influx — an act that federal authorities say would be unconstitutional since West Germany’s Basic Law stipulates that citizenship is available to all refugees of German ethnic stock and their descendants.

The reaction is another indication of how the sudden mellowing of the East German state and the crumbling of the Wall have taken the West by surprise. The West German government has done little or no planning to absorb the refugees: it has left the task of resettlement to states, cities and private charity. “There is no real contingency plan for reunification” either, admits a Kohl confidant. Only in recent days has a small group been assigned to examine the reunification question, and it has not even been given office space.

Much will depend, of course, on whether, and how soon, Krenz delivers on his rhetoric of freedom. The conviction that they will be able to decide their future could indeed keep at home most East Germans who are now tempted to flee; it is difficult to see anything else that might. Until the opening of the Wall, however, Krenz’s reformist inclinations had seemed ambiguous. For many years he had been a faithful follower of Honecker’s, and as recently as September defended the Chinese government’s bloody suppression of pro- democracy demonstrators in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. His conversion seemed sparked less by ideological conviction than by a desperate desire to cling to power in the face of street protest and refugee hemorrhage.

Even some of last week’s moves were ambiguous. The mass resignation of the 44-member Cabinet was not so significant as it was dramatic, since the Cabinet had been a rubber stamp. Its dismissal, however, did serve to rid Krenz of Premier Willi Stoph, a Honecker loyalist. The dissolution of the 21-member Politburo, and its replacement with a slimmer ten-member body, was far more pointed, since that is where the real power lies. Some of its more notorious hard-liners got the ax, including Stoph; Erich Mielke, head of the despised state security apparatus; and Kurt Hager, chief party ideologist. Hans Modrow, 61, the Dresden party leader, was named to the Politburo and will be Premier in the new government. He has been likened alternately to Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, the reformist thorn in the Soviet President’s side. Some conservatives, however, remain in the reshaped Politburo, and the way Krenz rammed his slate through the Central Committee was scarcely an exercise in democracy.

The initial reforms, in any case, did not satisfy the opposition. “Dialogue is not the main course, it is just the appetizer,” proclaimed Jens Reich, a molecular biologist and leader of New Forum, the major dissident organization. Founded only in September, it claims 200,000 adherents and has just been recognized by the government, which originally declared it illegal. The opposition pledged to keep up the pressure for a free press, free elections and a new constitution stripped of the clause granting the Communist Party a monopoly on power.

The Central Committee responded in co-opting language. “The German Democratic Republic is in the midst of an awakening,” it declared. “A revolutionary people’s movement has brought into motion a process of great change.” Besides underlining its commitment to free elections, the committee promised separation of the Communist Party from the state, a “socialist planned economy oriented to market conditions,” legislative oversight of internal security, and freedom of press and assembly.

Thus, rhetorically at least, the opposition no longer gets an argument from the government. Gerhard Herder, East German Ambassador to the U.S., pledged reforms that “will radically change the structure and the way the G.D.R. will be governed. This development is irreversible. If there are still people alleging that all these changes are simply cosmetic, to grant the survival of the party, then let me say they are wrong.”

Yesterday, with the Wall still locking people in, such talk might have been hard to believe. Today, with the barrier chipped, battered and permeable, it is a good deal easier to accept. In the end it does not matter whether Eastern Europe’s Communists are reforming out of conviction or if, as one East German protest banner put it, THE PEOPLE LEAD — THE PARTY LIMPS BEHIND. What does matter is that the grim, fearsome Wall, for almost three decades a marker for relentless oppression, has overnight become something far different, a symbol of the failure of regimentation to suppress the human yearning for freedom. Ambassador Herder declared that the Wall will soon “disappear” physically, but it might almost better be left up as a reminder that the flame of freedom is inextinguishable — and that this time it burned brightly.

—Reported by Michael Duffy with Bush, James O. Jackson/Bonn and Ken Olsen/Berlin

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com