From the Aug. 31, 1962, issue of TIME

From the Aug. 31, 1962, issue of TIME

For a structure that stood only about 12 ft. high, the Berlin Wall left quite a mark on modern history. Throughout the 28 years during which it endured, TIME followed the wall’s surprise construction, those who died attempting to get across, and finally its fall and aftermath.

You can trace that tale through our timeline of the Berlin Wall’s history or, below, read how the wall went down in the words of those who were watching it happen:

Aug. 25, 1961: Berlin: The Wall

The Berlin Wall went up quickly and with no warning on Aug. 13, 1961. Though it was at that point less a wall than a fence, it startled the world. For nearly a decade, Berlin — a divided city situated within the Eastern portion of a divided country — had been the easiest way to cross from East Germany to West, but the East had been facing a dwindling population and took drastic measures despite earlier promises to preserve freedom of movement:

The scream of sirens and the clank of steel on cobblestones echoed down the mean, dark streets. Frightened East Berliners peeked from behind their curtains to see military convoys stretching for blocks. First came the motorcycle outriders, then jeeps, trucks and buses crammed with grim, steel-helmeted East German troops. Rattling in their wake were the tanks — squat Russian-built T-34s and T-54s. At each major intersection, a platoon peeled off and ground to a halt, guns at the ready. The rest headed on for the sector border, the 25-mile frontier that cuts through the heart of Berlin like a jagged piece of glass. As the troops arrived at scores of border points, cargo trucks were already unloading rolls of barbed wire, concrete posts, wooden horses, stone blocks, picks and shovels. When dawn came four hours later, a wall divided East Berlin from West for the first time in eight years.

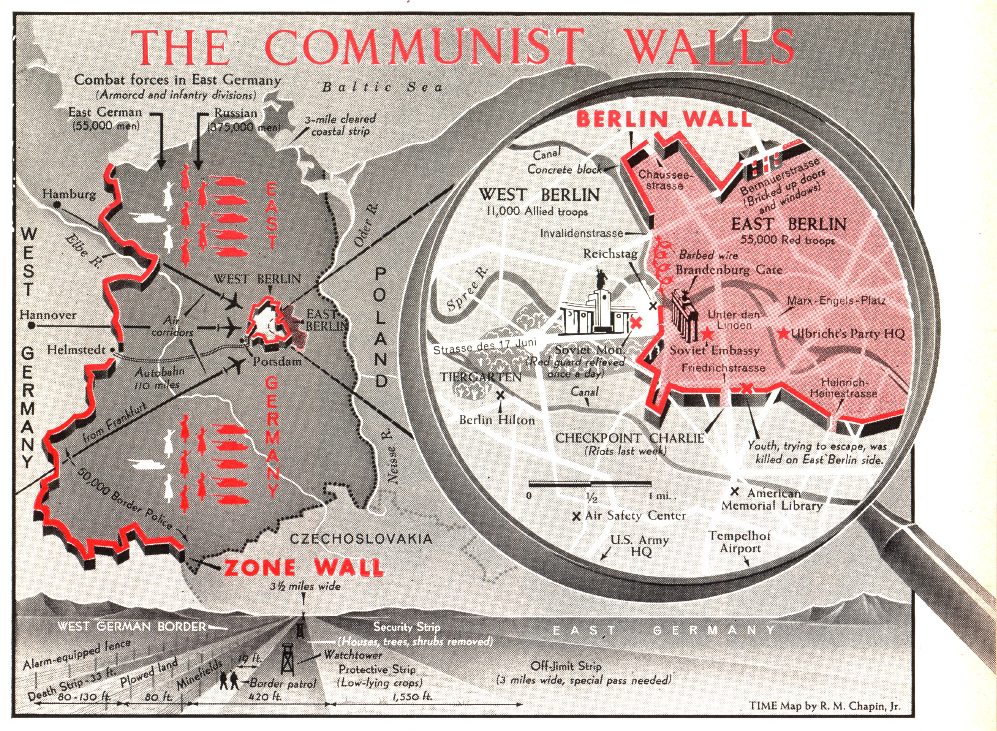

Aug. 31, 1962: Wall of Shame (see map at top)

A year later, protests erupted in West Berlin, sparked by cruel treatment of an attempted escapee named Peter Fechter — who was shot and left to bleed in the no-man’s-land between the two sides. TIME explored whether extended violence and further protest was likely to become a constant in the divided city, finding that many Berliners believed such an outcome unlikely but felt that the Wall would stand for the rest of their lives:

In flat, open country within the city’s northern boundary, the land to the west is checkered with brown wheatfields and lush, green, potato gardens. Eastward stretches a no-man’s land where once fertile fields lie desolate and deathly still. They could be in two different worlds—and, in a sense, they are. Even the countryside outside Berlin is divided into East and West by a vicious, impenetrable hedge of rusty barbed wire and concrete. As itsnakes southward toward the partitioned city, it becomes the Wall.

Seldom in history have blocks and mortar been so malevolently employed or sorichly hated in return. One year old this month, the Wall of Shame, as it is often called, cleaves Berlin’s war-scarred face like an unhealed wound; its hideousness offends the eye as its inhumanity hurts the heart. For 27 miles it coils through the city, amputating proud squares and busy thoroughfares, marching insolently across graveyards and gardens, dividing families and friends, transforming whole street-fronts into bricked-up blankness. “The Wall,” muses a Berlin policeman, “is not just sad. It is not just ridiculous. It is schizophrenic.”

Aug. 18, 1986: East-West Tale of a Sundered City by Jill Smolowe

On the 25th anniversary of the wall’s construction, TIME checked in on the city and found that Germans on the two sides of the Wall had evolved into two very different groups of people. West Berlin was more modern, East Berlin was quieter, their economies were distinct — but Berliners from both sides still harbored hopes that they would one day be reunited. Even with a quarter-century of division under their belt, they felt that they could all get along:

West Berliners have managed to make an uneasy peace with the monstrous Wall. Almost every Berliner’s emotional survival kit includes a wisecracking sense of humor. Standard encounter: an American, returning to Berlin after 60 years, asks his taxi driver to run down the events during his absence. Responds the driver: “The Nazis came, the war came, the Russians came. You didn’t miss much.” No less mordant are the graffiti spray-painted on the western side of the Wall. ALL IN ALL, YOU’RE JUST ANOTHER BRICK IN THE WALL, reads one bit of wisdom. DONALD DUCK FOR PRESIDENT, declares another. One of the newest decorations is a purple cake, divided in two by a brown wall. The inscription: HAPPY 25TH BIRTHDAY.

There are no clever messages on the eastern side of the Wall. East German officials regard the barricade with pride. To celebrate its anniversary, they plan to stage a parade and have already issued a commemorative postage stamp. “Since its construction,” says Karl-Heinz Gummich, a representative in the East German Tourist Office, “the economy has grown strong, relations with West Germany have been stabilized, and the threat of war has been removed.”

June 22, 1987: Back to the Berlin Wall by George J. Church

The Berlin Wall had already been the site of much speechifying when President Ronald Reagan appeared there in 1987 — but by that point, something that changed. In the USSR, the words glasnost and perestroika had entered the political vocabulary. Mikhail Gorbachev spoke of openness, and his influence in East Germany presented a glimmer of hope that the Berlin Wall might not be forever. Reagan urged that hope on with one of the most famous lines of his career: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this Wall.”

Before an audience estimated at 20,000, the President rose to the occasion. Referring to the city’s division and deliberately inviting comparison with John F. Kennedy’s famed “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in 1963, Reagan expressed “this unalterable belief: es gibt nur ein Berlin” (there is only one Berlin). Taking note of the violent demonstrations against U.S. foreign policy that swirled through West Berlin before his arrival, Reagan asserted, “I invite those who protest today to mark this fact: because we remained strong, the Soviets came back to the table” and are on the verge of a treaty “eliminating, for the first time, an entire class of nuclear weapons.”

Oct. 16, 1989: Freedom Train by William R. Doerner

On the occasion of Eat Germany’s 40th birthday, the Berlin Wall had begun to lose its oomph. Originally meant to prevent traffic between the two sides of the city, it was made far less effective when it became possible to get to West Germany by other routes:

So far this year, more than 110,000 East Germans have left, far and away the most since the Berlin Wall went up in 1961. Slightly more than half have departed with official permission, a sign that the Honecker regime has been forced to relax its policy of limiting emigration to the elderly and a few political dissidents. According to West German officials, some 1.8 million East Germans — more than 10% of the population — have applied to leave, despite the risk of job and educational discrimination.

But growing numbers refuse to wait for permission. In August and September, more than 30,000 vacationers took advantage of the newly opened border between Hungary and Austria to cross into West Germany. East Berlin tightened controls on travel to Hungary, yet new refugees continue to slip over at the rate of 200 to 500 a day. Hungary has rejected any suggestion that it close its borders.

Nov. 20, 1989: Freedom! by George J. Church

Until the Wall fell at midnight on Nov. 9, 1989 — losing its power as suddenly as it had gone up, though it would take many months for the concrete to be dismantled — TIME had been planning to run a cover story about the election of the first black governor in the United States, Doug Wilder of Virginia. But, as then-managing editor Henry Muller recounted in a letter to readers, “then came the stunning announcement that East Germans be allowed to travel through the Berlin Wall and would be granted freer elections as well. Bonn bureau chief Jim Jackson called me to urge that we change the cover, but my fellow editors and I hardly needed to be persuaded.” The result was 12 pages of reporting and photography and, as Muller put it, “history as it is made, each day and each week”:

What happened in Berlin last week was a combination of the fall of the Bastille and a New Year’s Eve blowout, of revolution and celebration. At the stroke of midnight on Nov. 9, a date that not only Germans would remember, thousands who had gathered on both sides of the Wall let out a roar and started going through it, as well as up and over. West Berliners pulled East Berliners to the top of the barrier along which in years past many an East German had been shot while trying to escape; at times the Wall almost disappeared beneath waves of humanity. They tooted trumpets and danced on the top. They brought out hammers and chisels and whacked away at the hated symbol of imprisonment, knocking loose chunks of concrete and waving them triumphantly before television cameras. They spilled out into the streets of West Berlin for a champagne-spraying, horn-honking bash that continued well past dawn, into the following day and then another dawn. As the daily BZ would headline: BERLIN IS BERLIN AGAIN.

Dec. 4, 1989: Selling a Piece of the Rock

Coverage of the wall’s fall wasn’t all about serious pronouncements on the future of Europe. There were also some gems like this one, the story of some American entrepreneurs who were marketing chunks of the Wall as timely gifts for that holiday season:

Last week two shipments of gray and white rubble, totaling 20 tons, were airlifted from Germany to Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport. The Missouri entrepreneurs who imported the debris swear that it comes from demolished portions of the Berlin Wall. Just in time for the Christmas shopping season, they will split it into 2-oz. chunks to be sold, along with an “informative booklet and a declaration of authenticity,” for $10 to $15 in gift shops and department stores.

Dec. 18, 1989: What the Future Holds by Frederick Painton

About a month after the Wall fell, TIME gathered five experts on European politics and economics to predict what would be next for the continent — including whether the end of the Wall would inevitably lead to the reunification of Germany:

For the third time in this century the old order is crumbling in Europe, and the world waits anxiously for a new one to be born. The transition promises to be long, difficult and hazardous. But rarely if ever has the vision of a peaceful and relatively free Europe stretching from the Atlantic to the Urals seemed so palpably within grasp. Thus 1989 is destined to join other dates in history — 1918 and 1945 — that schoolchildren are required to remember, another year when an era ended, in this case the 44-year postwar period, which is closing with the rapid unraveling of the Soviet empire.

Oct. 8, 1990: Germany: And Now There Is One by Bruce W. Nelan

In their rush toward unification over the past 11 months, East and West Germany struck down the barriers between them like so many tenpins. The most unforgettable and heart-quickening breakthrough was the first, the fall of the Berlin Wall last Nov. 9. Then came free elections in the East on March 18, economic union on July 1, and the Sept. 12 agreement of the four World War II Allies to end their remaining occupation rights in Berlin.

Any of those could be taken as the date on which unification became inevitable. But the date that will be celebrated in the future Germany comes this week, Oct. 3, when the Freedom Bell in West Berlin’s Schoneberg city hall tolls and the flag of the Federal Republic of Germany is raised in front of the 96-year-old Reichstag building. At that moment, the German Democratic Republic, a relic of Stalin’s postwar empire, ceases to exist.

Read more about the fall of the Berlin Wall here in TIME’s archives, where the Nov. 20, 1989, cover story is now available.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com