This post originally appeared on Rolling Stone.

Many of us have random impulses, but Bill Murray is the man who acts on them, for all of us. Consider, for example, the time a couple of years ago when he caught a cab late at night in Oakland. Facing a long drive across the bay to Sausalito, he started talking with his cabbie and discovered that his driver was a frustrated saxophone player: He never had enough time to practice, because he was driving a taxi 14 hours a day. Murray told the cabbie to pull over and get his horn out of the trunk; the cabbie could play it in the back seat while Murray drove.

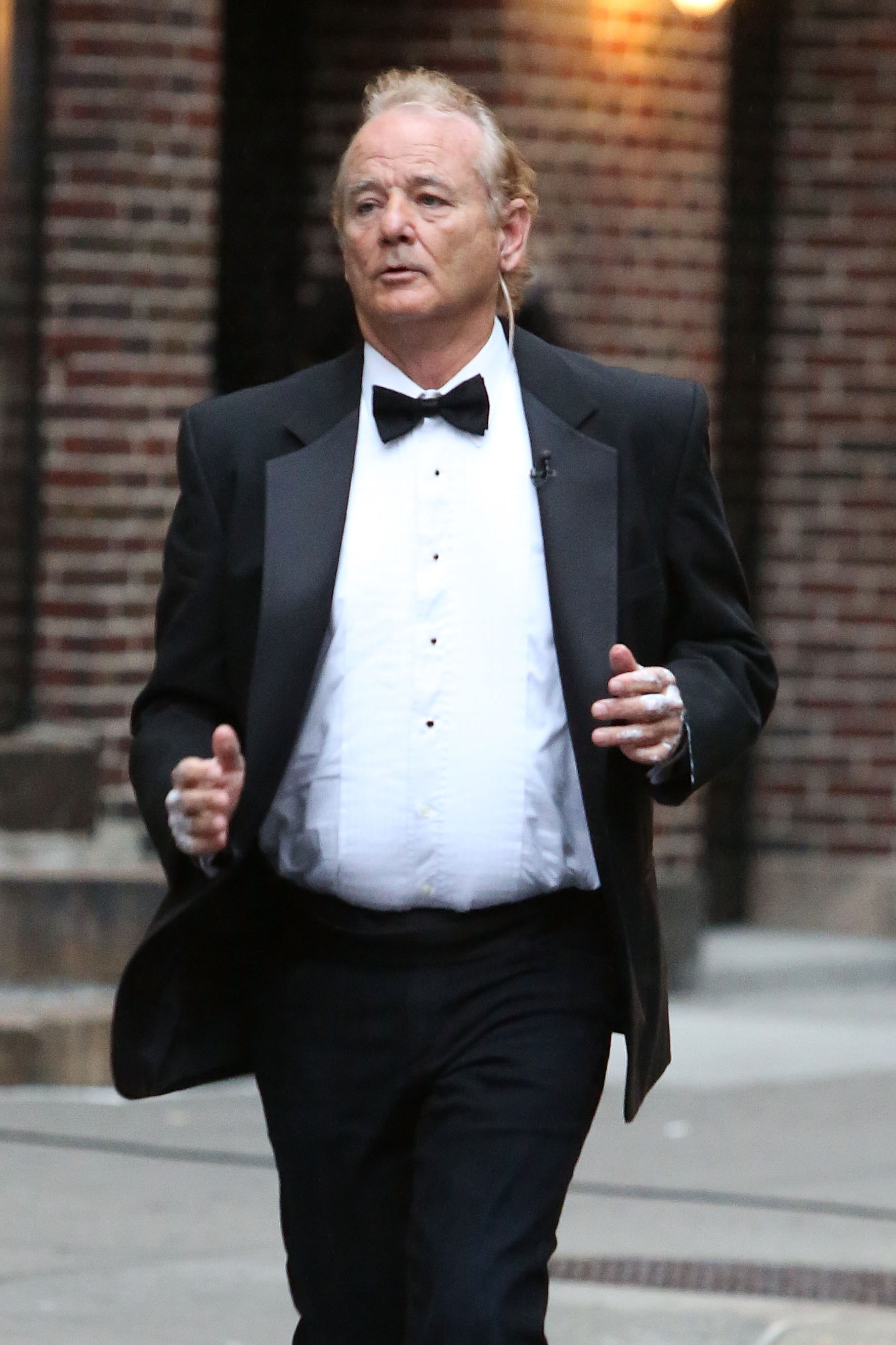

As he tells this story, Murray is sitting on a couch in a Toronto hotel. Wearing a rumpled shirt with purple stripes, he looks like he’d rather be playing golf than doing an interview. But his eyes light up as he remembers the sound of the cab’s trunk opening: “This is gonna be a good one,” he thought. “We’re both going to dig the shit out of this.” Then he decided to “go all the way” and asked the back-seat saxophonist if he was hungry. The cabbie knew a great late-night BBQ place, but worried that it was in a sketchy neighborhood. “I was like, ‘Relax, you got the horn,'” says Murray. So around 2:15 a.m., Bill Murray ate Oakland barbecue while his cab driver blew on the saxophone for an astonished crowd. “It was awesome,” Murray says. “I think we’d all do that.”

In fact, most of us wouldn’t (although we probably should). Most of us don’t crash strangers’ karaoke parties, or get behind a bar in Austin to fulfill all drink orders from whatever random bottle was handy, or give a kid $5 to ride his bike into a swimming pool. Murray has done all those things, and more. The world has an apparently bottomless hunger for true stories of Bill Murray making strangers’ lives stranger, and he obliges, whether he’s stealing a golf cart and driving it to a nightclub in Stockholm or reading poetry to construction workers. He makes our world a little bit weirder, the mundane routines of everyday life a little more exciting, or as Naomi Watts puts it, “Wherever he goes, he’s leaving a trail of hysteria behind him.”

When Lost in Translation was released in 2003 (Murray got an Oscar nomination for playing an aging movie star stranded in the same luxury Tokyo hotel as Scarlett Johansson), I asked director Sofia Coppola what her wish for the following year was. She looked startled. “My wish came true,” she said. “Bill Murray did my movie.”

Murray, 64, has not made it easy to get him to be in your movie. Unlike any other actor of his stature, he has no agent, no manager, no publicist. If you want to cast him, you get a friend of his to persuade him. Or you call his secret 1-800 number and leave your pitch after the tone. If he checks his voicemail, maybe he’ll call you back. After he agrees to be in your movie, you may not hear from him again until the first day of shooting, when he’ll show up in the makeup trailer, cracking jokes and giving back rubs. Sometimes his inaccessibility means that he misses out on films he would have excelled in – Little Miss Sunshine, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Monsters, Inc. – but Murray isn’t particularly concerned. It’s a worthwhile trade-off for him, considering that what he gets in return is freedom.

“Bill’s whole life is in the moment,” says Ted Melfi, who directed Murray in the new movie St. Vincent. “He doesn’t care about what just happened. He doesn’t think about what’s going to happen. He doesn’t even book round-trip tickets. Bill buys one-ways and then decides when he wants to go home.”

To persuade Murray to be in his movie, Melfi left a dozen voicemail messages, sent a letter, mailed scripts to P.O. boxes all over the country – and then on a Sunday morning, he got a text asking him to meet Murray at LAX an hour later. They drove through the desert for three hours, stopping at an In-N-Out Burger for grilled-cheese sandwiches, and by the end of the ride Murray had signed on. Melfi had one request: Please tell somebody else that this happened, because nobody is ever going to believe me.

MORE: Bill Murray Talks Turning Down ‘Forrest Gump,’ ‘Philadelphia’ Roles

Murray plays the title role in St. Vincent: a Vietnam vet with a weakness for booze and gambling. He becomes the cantankerous baby sitter for the kid next door, in a relationship that feels like a reprise of 1979’s Meatballs, if Murray’s counselor character, Tripper Harrison, had a few decades of hard living under his belt. The movie walks the line of mawkishness, but it works because of Murray’s unsentimental performance.

Like all of Murray’s best film work, it originates in his stress-free mentality. “Someone told me some secrets early on about living,” Murray tells a crowd of Canadian film fans celebrating “Bill Murray Day” that same weekend. “You can do the very best you can when you’re very, very relaxed.” He says that’s why he got into acting: “I realized the more fun I had, the better I did.” On the set, the pleasure he takes in performing doesn’t end when the camera stops rolling.

“It was sometimes challenging to get Bill to come to set,” Melfi says, “not because he’s a diva but because we couldn’t find him.” He would wander away, or hop on a scooter, or drop by an Army recruiting center. The movie hired a production assistant just to follow Murray around, but he was always able to lose her.

Murray’s St. Vincent co-star Melissa McCarthy confides, “Bill literally throws banana peels in front of people.” I assume she’s using “literally” to mean “metaphorically,” as many people do, but it turns out to be true: Once during a break in filming when the lights were getting reset, Murray tossed banana peels in the paths of passing crew members. “Not to make them slip,” McCarthy clarifies, “but for the look on their face when they’re like, ‘Is that really a banana peel in front of me?'”

Murray transforms even the most mundane interactions into opportunities for improvisational comedy. Peter Chatzky, a financial-software developer from Briarcliff Manor, New York, remembers being on vacation at a hotel in Naples, Florida, when his grade-school kids spotted Murray having a drink poolside and asked him for autographs. Murray gruffly offered to inscribe their forearms but ended up writing on a couple of napkins instead. Jake, a skinny kid, got “Maybe lose a little weight, bud,” signed “Jim Belushi.” Julia got “Looking good, princess. Call me,” signed “Rob Lowe.”

Murray grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, the fifth of nine children. His father, a lumber salesman, died when Bill was 17. He spent his 20th birthday in jail, having been busted at a Chicago airport with eight and a half pounds of weed. After he got out on probation, he pursued acting; six years later, he broke through on the second season of Saturday Night Live. These days, Murray spends a lot of his time in Charleston, South Carolina, where he is part-owner of the minor-league baseball team the Charleston RiverDogs. As “director of fun,” Murray will dress up in a hot dog costume, or even run around the tarp-covered diamond during a rain delay, concluding with a belly-flop slide – safe at home. So many people in Charleston have Bill Murray stories and sightings that a local radio station instituted a regular “Where’s Bill?” feature.

MORE: In Pics: A Short History of Bill Murray’s Offscreen Antics

Recently, Murray attended a birthday dinner in Jedburg, South Carolina, invited by the chef Brett McKee. “My youngest daughter used to date his youngest son,” McKee says. “The party was in the middle of freaking nowhere, with people Bill didn’t know, and he was great – he was just hanging out like a regular dude. A couple of the guests were old country people, and they were showing him their moose calls.” After dinner, there was dancing; Murray commandeered the remote control and was captured on video getting down to his selections: Tommy Tutone’s “867-5309/Jenny,” and DJ Snake and Lil Jon’s “Turn Down for What.”

In April, Ashley Donald and her fiancé, Erik Rogers, were in downtown Charleston, posing for their engagement photos in front of historic houses. “As our photographer took a picture,” she recalls, “we noticed a guy standing behind him, lifting his shirt over his face and rubbing his belly.” Then he pulled down his shirt, revealing that he was Bill Murray. The betrothed couple were flabbergasted, but had enough presence of mind to ask him to take a picture with them. Murray posed, congratulated them and kept walking.

Murray made international news in May when he gave a toast at tech-startup manager EJ Rumpke’s bachelor party, at a steakhouse in Charleston. Murray didn’t technically crash – one of Rumpke’s friends spotted him at the restaurant and invited him – but he took the opportunity to drop some bona fide wisdom, telling the guys that just as funerals are actually for the living, bachelor parties are actually for unmarried friends. He advised the guests that if they found someone they thought they wanted to spend their lives with, they shouldn’t plan a wedding and book a caterer, but should travel around the world. And if they were still in love on their return to the States, “get married at the airport.”

“He grabbed my leg and threw me up in the air,” Rumpke says. “And then he snuck out.” Rumpke got married without a global journey, but Murray says that one of his own friends tried the scheme – and it worked out terribly. “The next time I saw him, he leapt all over me, because he was on his way down the slippery chute and he found out that was really the wrong thing,” Murray says with a grin. “He was very happy about it.”

The website urban dictionary defines “Bill Murray Story” as “an outlandish (yet plausible) story that involves you witnessing Bill Murray doing something totally unusual, often followed by him walking up to you and whispering, ‘No one will ever believe you.’ ” Ask Murray about his reputation as the master of surreal celebrity encounters and he grimaces, not eager to explain his motivations. But he will concede that he’s aware of how his presence is received. “No one has an easy life,” he says. “It’s this face we put on, that we’re not all getting rained on. But you can’t start thinking about numbers – if I can change just one person, or I had three nice encounters. You can’t think that way, because you’re certainly going to have one where you say, ‘What did I just do?’ You’re a disappointment to yourself, and others, imminently. Any second.”

Sitting at a table in the upscale Toronto restaurant Montecito, which he co-owns, filmmaker Ivan Reitman laughs as he remembers a day 40 years ago. He was producing a theatrical revue called The National Lampoon Show, starring John Belushi, Gilda Radner, Harold Ramis, Bill Murray and Bill’s brother Brian – before SNL. Reitman walked down the streets of New York with Bill, who was totally unknown, but was already treating the universe as his own private playground. Murray adopted what they called “the honker voice” – the obnoxious voice he later used in Caddyshack. “As we were walking across the street,” Reitman says, “he would yell at the top of his lungs, ‘Watch out! There’s a lobster loose!’ He would see somebody in the street and say, ‘Hey, get some hot butter, it’s the only way to get ’em!’ They would start laughing. They didn’t know who this crazy person was, but they knew he was funny.”

MORE: In Pics: The 20 Greatest Bill Murray Movies

In 1978, when Reitman was putting together Meatballs, he spent a month persuading the 27-year-old Murray to do the movie. At that point, he had a phone number that you could actually get him on. Murray wanted to spend his summer off from Saturday Night Live playing baseball and golf, but Reitman pleaded, and Belushi advised Murray that it didn’t matter what the movie was, so long as he was the star. Meatballs set the template for Murray’s working methods: He closed his deal the day before the movie started shooting and routinely ignored the script. His first day, he improvised his way through a scene where he’s introducing all the counselors-in-training – he showed up, read the pages and threw them away, saying, “I got this.”

When Murray first saw an action scene cut together from 1984’s Ghostbusters, he says, “I knew then I was going to be rich and famous. Not only did I go back to work with a lot of attitude, I was late. I didn’t care – I knew that we could be late every day for the rest of our lives.”

Reitman leans back. “He lives his life to his standard, even though sometimes he’s lazy and sometimes he’s eccentric, and he’s frustrating to other creative people, and, frankly, unfair, because everything has to go on his clock,” he says. “But he’s worth it.”

Melfi says there’s no difference between the public Murray and the private Murray: “What you see is what you get. He throws people in the pool in public, and he throws people in the pool in private.”

Sitting in his hotel room, Murray gently disagrees. “The private me just gets lost and wanders, and is more easily bushwhacked and taken down for dreaming nonsensical stuff. The public me can get a bit more emotional because people are pushing my buttons. But when I’m at my best? The working part of me. I get a lot more done. By really getting into your work, the nonessential stuff drops away.” Through this lens, Murray’s ongoing adventures with the public can be considered an effort to make real life more like the movies.

In 2011, Murray filmed a promotional video for the Trident Academy near Charleston; one of his six sons was a student there. (Murray has been married and divorced twice.) Director David W. Smith was working on the shoot. “He came in hot and a little grumpy,” Smith says. “He was about 30 minutes late, and he complained that there were too many lights. He had a script, but he sat down in the school library and ad-libbed the whole thing. He got all these teddy bears and had a conversation with them. We’re looking at each other – this guy is off-his-face crazy – but there was a method to his madness.”

Murray loosened up as he played basketball with the school’s kids, and stuck around for lunch (his request: a tuna sandwich with no crusts), ultimately signing autographs and taking pictures. Smith recalls, “As the shoot went on, he became more and more like the guy that everyone thinks they know, which I guess is who he actually is.” Smith asked Murray if he would walk down the hall with the crew members so they could make a short film of it. Murray was confused, but he complied – when the camera cut, he kept walking, heading to his car without breaking stride.

Smith played the footage in slow motion, set an old Kinks song to it and had a short Bill Murray film that looked like an outtake from a Wes Anderson movie. Ultimately, about 2 million people watched an online one-minute film of Bill Murray (and four other guys) walking down a hallway in slow motion. Smith had internalized one of Murray’s principles: Don’t accept the world as it is, but find some way to inject life into its most mundane moments.

Another essential Murray principle: Wear your wisdom lightly, so insights arrive as punch lines. When pressed about his interactions with the public, he admits that the encounters are, to a certain extent, “selfish.” Murray shifts his weight on the couch and explains, “My hope, always, is that it’s going to wake me up. I’m only connected for seconds, minutes a day, sometimes. And suddenly, you go, ‘Holy cow, I’ve been asleep for two days. I’ve been doing things, but I’m just out.’ If I see someone who’s out cold on their feet, I’m going to try to wake that person up. It’s what I’d want someone to do for me. Wake me the hell up and come back to the planet.”

Doing a Q&A at a Toronto movie theater, Murray is asked, “How does it feel to be Bill Murray?” – and he takes the extremely meta query seriously, asking the audience to consider the sensation of self-awareness. “There’s a wonderful sense of well-being that begins to circulate . . . up and down your spine,” Murray says. “And you feel something that makes you almost want to smile. So what’s it like to be me? Ask yourself, ‘What’s it like to be me?‘ The only way we’ll ever know what it’s like to be you is if you work your best at being you as often as you can, and keep reminding yourself that’s where home is.” As the audience applauds, Bill Murray smiles inscrutably, alone in a crowded room, safe at home.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Contact us at letters@time.com