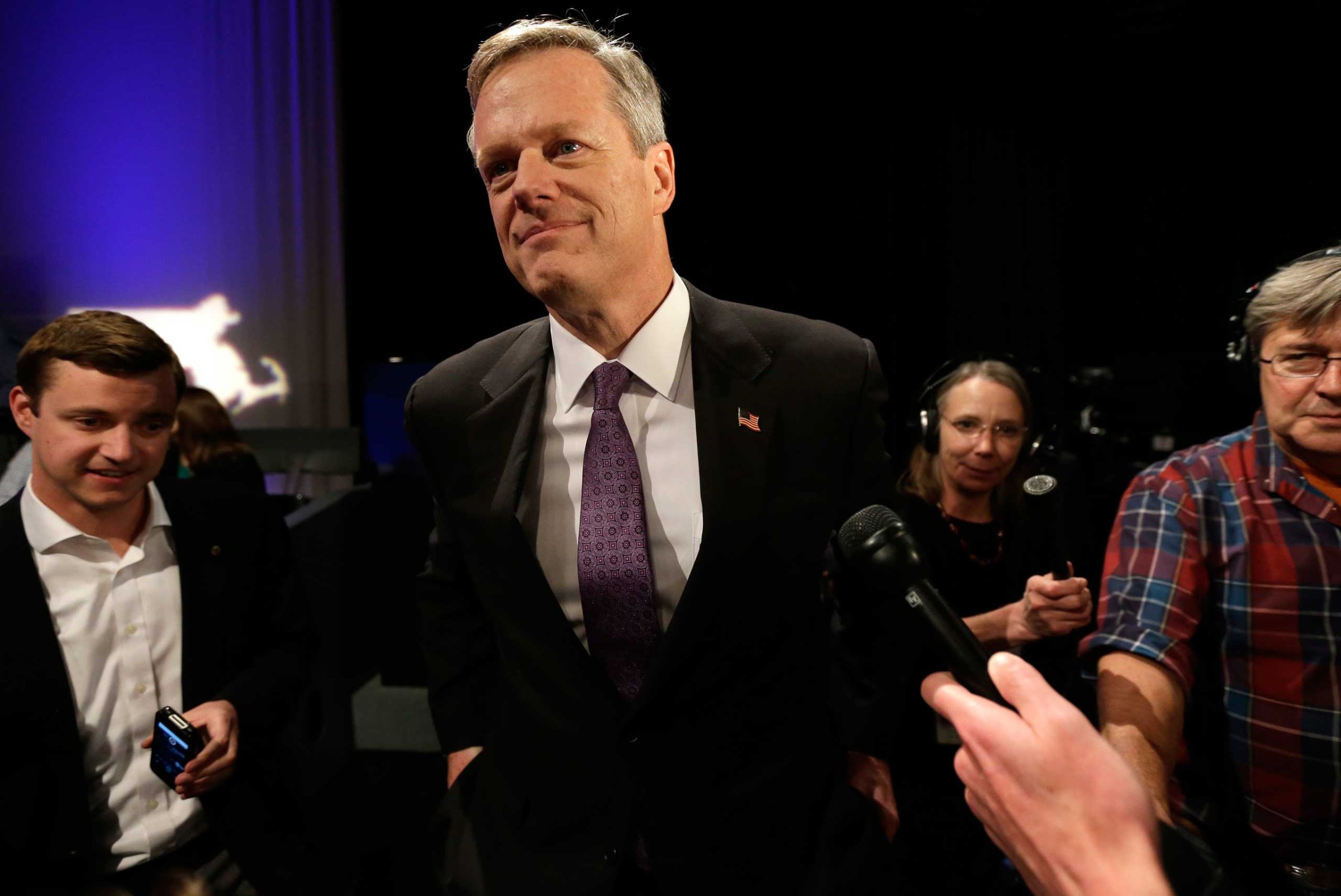

Politicians abhor dead silence. But for 31 seconds, Charlie Baker sat on a debate stage, staring at the ceiling, and wracking his brain for the answer to the thorniest question he’s fielded since he jumped into the race for Massachusetts governor last year. The question: Name a current politician who’s a role model for you. “Um… um…. You know, you’re kind of stumping me here,” Baker said. After 31 seconds of stammering and silence, he finally ventured, “Um, how about Jeb Bush?”

Baker has been locked in a tight race for governor of Massachusetts for months. Recent polls have shown him leading his Democratic opponent, state Attorney General Martha Coakley, by as little as a single point. Still, the most uncomfortable Baker has been all campaign hasn’t been in the final, frenetic dash toward Election Day, but in that primary campaign debate in late August, when he was forced to identify himself with another Republican.

That’s because Baker is a throwback to a kind of Republican politics that no longer exists at any meaningful scale. It’s what has the former health insurance company CEO within reach of the State House in Boston. But it’s also what makes the final step so difficult to pull off.

Baker is running without much company. The only other Republican in Massachusetts with a shot at major office is Richard Tisei, a former state legislator, and Baker’s 2010 running mate, who’s in a tight race for Congress in the suburbs north of Boston. “I think running as a moderate anything is more complicated than it used to be. That’s the nature of our politics these days,” Baker says. “I think having a different set of viewpoints within the Republican party in New England, and nationally, is a good thing, not a bad thing.”

Democrats dominate Massachusetts politics. The state Republican Party claims less than 11% of all registered voters. Massachusetts hasn’t sent a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives since 1994. The outgoing governor, Deval Patrick, stormed into office on a campaign that political strategist David Axelrod used to test-drive the themes that took Barack Obama to the White House in 2008. The state flirted briefly with Scott Brown, then turned on him so violently that he fled across the border, to New Hampshire. In Brown’s place, Massachusetts voters installed Senator Elizabeth Warren, a populist who’s pulling the entire Democratic party leftward.

Yet Massachusetts voters have a history of electing a certain kind of Republican to lead the state. The last two Democratic governors are Patrick and Michael Dukakis; between the two of them lies a 16-year stretch of Republican rule. The problem for Baker is that moderate New England Republicans have almost vanished as a political force.

Baker, 57, has long been the state GOP’s brightest star. He rose to political prominence two decades ago in the cabinet of then-Governor Bill Weld. Weld was a Republican who rode a tax revolt into office, but he was so far to the left on social issues that he won in liberal enclaves like Cambridge and Amherst. Baker’s politics echo Weld’s. As health secretary and then budget chief for Weld and his successor, Paul Cellucci, Baker earned a reputation as a sharp policy mind and number cruncher, but was not known as an ideologue.

“He’s the smartest guy in the room, but he doesn’t act like it,” says Jay Ash, the city manager of Chelsea, a small, heavily Central American community just north of Boston. “He’s inquisitive, and he doesn’t dismiss people’s views. He’s open and engaging on the issues.”

“I worked in an administration that was pretty successful in working across the aisle to get stuff done with Democrats,” Baker says. “A lot of our successes were because we had two teams on the field, competition and political engagement. Whether voters decide that’s what they want or not is going to be up to them. I certainly wanted to run a race built on that kind of message and approach.”

Ash and Baker met in the early 1990’s, when Chelsea was operating in state fiscal receivership. They’ve been friends since, yet Baker didn’t get Ash’s vote four years ago, when Baker made his first run for governor. Baker’s 2010 campaign was filled with stunts meant to generate voter outrage, like displaying a prop welfare card that said it could be swiped for booze and lottery tickets at taxpayer expense. The disgruntled turnout wasn’t enough and Baker lost to Patrick with 42% of the vote.

The Massachusetts governor’s race is a redemption run for both Baker and Coakley. Coakley lost the 2010 contest for Ted Kennedy’s former Senate seat to Brown in spectacular fashion, and reporters are salivating over storylines about Coakley blowing another high-profile race against another Massachusetts Republican. Coakley has been a popular attorney general, though, and she’s run hard for governor. Their race is neck-and-neck less because Coakley has done something wrong, than because Baker has done a whole lot right.

Baker has managed to run for political office while mostly taking divisive politics off the table. He has beaten the drum on a few red meat Republican issues, like lowering taxes and hardening work rules for welfare. But the bulk of his campaign has been focused on education and economic opportunity, and in these areas, he’s driving a debate that’s less about political vision than it is about competence in managing government. He’s bent the race to his strengths, and made the contest a referendum on putting a policy wonk in the governor’s office.

Baker has also gone to lengths to play up his social liberalism, releasing campaign videos with his brother, who’s gay and married, and with his teenage daughter, who assures him on-camera, “You’re totally pro-choice and bipartisan.”

“Ideologically, he’s where the majority of people in Massachusetts are,” says Larry DiCara, a prominent Democratic attorney in Boston.

“In some states, he’d be a Democrat,” says Ash, who praises his friend’s current run. “He’s with Democrats and independents on social issues.”

Baker is also with Democrats in a more literal sense. On the trail, he has taken the fight to Coakley in the urban centers that normally hand Democrats lopsided vote margins. Baker is trying to raid the Democratic base, aggressively courting votes in Irish pubs and mill towns. He’s held over 150 campaign events in Boston — an unheard-of presence in a city where voters normally hang 40-plus-point losses on Republicans. Baker lost the city by 47 points in 2010; a recent WBUR poll had him cutting that deficit in half.

“You have to make the sale, but you can’t make the sale if you don’t show up,” Baker reasons.

And as he tries to close the deal, he’s doing it without much support from state Republicans. Massachusetts Democrats enjoy an enormous campaign volunteer base, the machinery of organized labor, and star power in Washington, DC. As the campaign entered the home stretch, Michelle Obama, Bill and Hillary Clinton, and Vice President Joe Biden all swung through to rally the party faithful for Coakley. Weld, who’s now working as a rainmaker at a Boston law firm, is the closest thing Baker has had to a star campaign surrogate.

Baker’s party doesn’t have the bodies to compete with Democrats on the grassroots level. (His campaign has knocked on 270,000 doors this election cycle, a huge number for a Massachusetts Republican; Elizabeth Warren’s campaign hit 240,000 doors in a single weekend two years ago.) But he has received one major outside boost: the Republican Governors Association PAC has spent more than $12 million on the race, over two-and-half times what they spent on the 2010 campaign and more than the combined spending of Baker and Coakley’s own campaigns.

But national Republicans will be hard-pressed to find broader lessons. If Baker wins, it will be because he won over Democratic voters and narrowed the daylight between his partisans, and Coakley’s. That isn’t a formula that has legs far outside Boston.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com