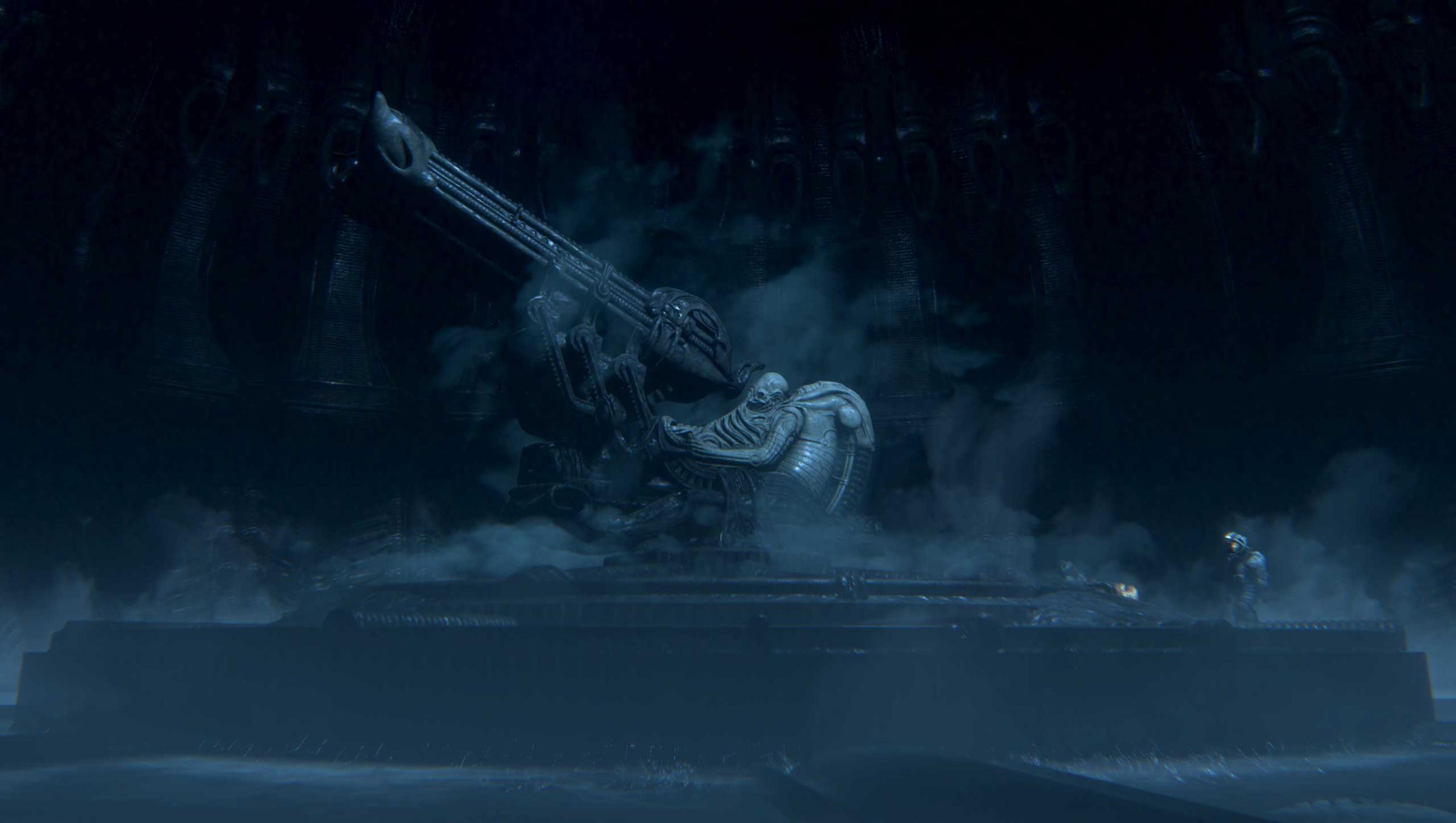

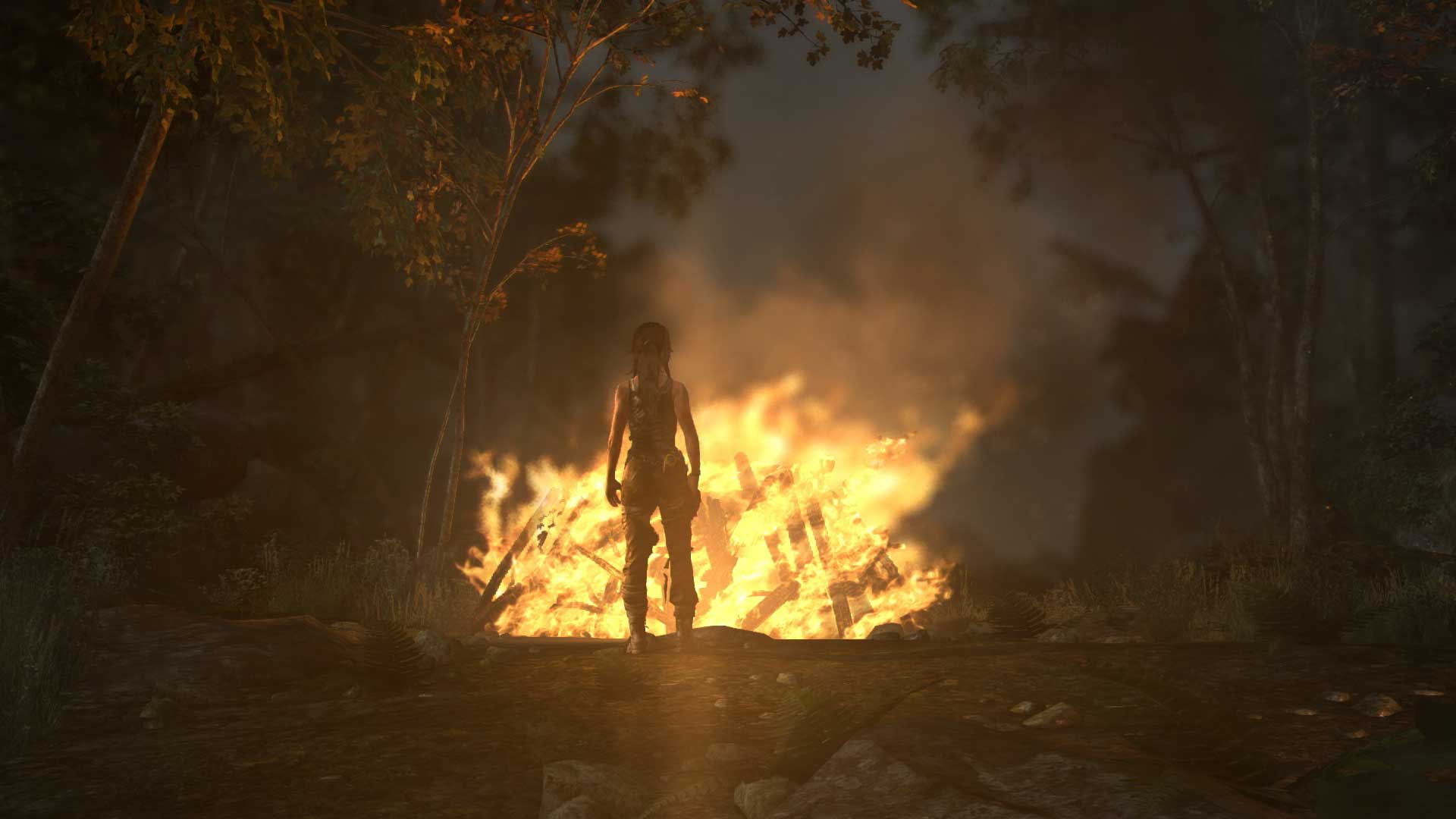

Scouting the rain-hammered shoreline of a coastal region in Dragon Age: Inquisition, one of my companions spies a giant with tusks thick as logs trading blows with a dragon. “Badass,” he says, chuckling. And I stop to watch, because it is badass, like so much else in this alien otherworld: the sun flaring like a UFO in a forest of trees tall as redwoods; skies that look by turns cerulean or bloomy or haunted or storm-wracked; phantasmagoric landscapes with deranged rock cities and archetypal motifs out of a Jungian nightmare; dragons spitting fireballs like meteors.

Which is strange, because you could argue the Dragon Age games up to now have been the opposite of impressive, with pedestrian visuals, anticlimactic battles, fiddly interfaces and narrative non sequiturs. Theirs were societies saved not by long-slogging armies or international diplomacy, but scrappy squads of godlike activists.

Bioware’s best known for the latter, devotedly tilling ground popularized by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in the 1970s. The Canadian studio’s second game in the late 1990s was a licensed Dungeons & Dragons homage, which begat a minor renaissance in computerized D&D-play. But the studio slaved itself to that system’s ideas, and when Dragon Age: Origins arrived over a decade later, we were still, in essence, replaying Baldur’s Gate: a choose-your-own-adventure bricked together by peripatetic exploration, reductive arithmetic and relentless conflict resolution.

Dragon Age: Inquisition, the latest installment for game consoles and Windows, isn’t a seas-parting rethink–it’s invested in the same basic ideas about roleplaying as its predecessors. But here it employs them on a scale we haven’t seen since a meme about career-ending missiles graced one of the most popular shows on TV.

This, finally, is Bioware world-building with the mythic sweep of a Peter Jackson or Todd Howard, cultivating a sleek, reimagined, wildly blown up rendition of writer David Gaider’s fantasy preserve that feels at once grander and more holistic, a world whose craftsmanship you can admire and at points obsess over and occasionally even gawp at. If Dragon Age II was a weird, turtling retreat to button-mashy, bam-pow brawls in a village-sized city patched together from generic, recycled components, Dragon Age: Inquisition feels like the yang to its yin. On an epic scale.

Some may worry, hearing the setup, that it borrows too much from Bethesda’s Oblivion. As in that game, breaches in space-time have appeared around the world from which demons pour forth. Your job, as the amnesiac leader of a group that calls itself an “inquisition” but behaves more like a magnanimous oligarchy, is to go around sealing the holes and righting wrongs.

But The Elder Scrolls games take fewer risks, and though the writing isn’t appreciably better here, Inquisition engages edgier concerns: religious belief (or lack thereof), same-sex relationships, the psychological horrors of war, racial bigotry and economic classism to name a few. Yes, you’re still obliged to de-villain caves and dungeons, and there’s still too much errand-running, but you’ll also get to wrestle weightier subject matter. So for instance: the fractious relationship between a father and, in the series’ first treatment of an openly gay character, his son. If the writing in the end hews nearer Tolkien than Peake when it’s trying to subvert cliché, at least it’s trying.

For all its Game of Thrones flavoring, you’re either fighting stuff or getting ready to fight stuff between Inquisition‘s story beats, and combat hasn’t been a series strong point. Dragon Age: Origins, the first game, saddled an already fiddly battle system with a laborious interface, while Dragon Age II dispensed with tactical nuance and went for mediocre leap-and-dodge combat instead.

Stumble into a clutch of bad guys in Inquisition, by contrast, and yes, you can still hammer buttons to conjure ability flourishes or batter opponents, but you’ll get better results if you pace yourself in the rejiggered tactical view. Tap a button and the game freezes, letting you glide over the battlefield like a steadicam operator, inspecting friend or foe at leisure, finessing melee or distance attacks and coordinating flanking maneuvers. Once you’ve finished, you can hold another button to roll the clock forward or shift back to real-time mode. It’s a remarkably elegant system that’s both lively and nuanced, scalable complexity on a gamepad that works.

Eventually the game you thought you were playing–the one where you pingpong from quest to quest and battle to battle–becomes a game within a game, as you’re asked to deploy allies to complete timed missions to gain power or influence, which you then spend at a home base “war table,” unlocking new areas or increasing the rank of the inquisition or selecting perks with effects that ripple through the other gameplay systems. Without spoiling plot points, I can say that what starts as a thing about making do with what’s at hand eventually becomes a thing about building bigger and better. Home improvement in a game is nothing new, but it’s handled competently here, and has its own satisfying wrinkles.

A few problems remain: Why can you “rest” and refresh your party just a few yards from attacking enemies? Why place lengthy background text on ephemeral loading screens that vanish after a few seconds? Why can’t I follow more precisely the impact of my dialogue choices? Why are folks still leaving treasure-filled chests in the middle of nowhere? Must so many quests still depend on the quest-givers being fundamentally lazy? And why, in a story about an inter-dimensional apocalypse, would anyone ask a bunch of super-beings to slaughter a dozen rams to load up on ram meat?

Dragon Age: Inquisition didn’t work for me at first, but then I realized I’d been playing it too much like Dragon Age II, mashing through battles and racing between to-dos and ignoring the filler because why would Bioware know anything about riveting world design? Then I slowed down, and in slowing down discovered how wrong I’d been–how much more the design team managed to fill this iteration with. Sometimes gaming’s as much about the caught-you-off-guard zen moments as the lunatic action ones, and sometimes the workmanship’s enough.

4.5 out of 5

Reviewed using the PlayStation 4 version of the game.

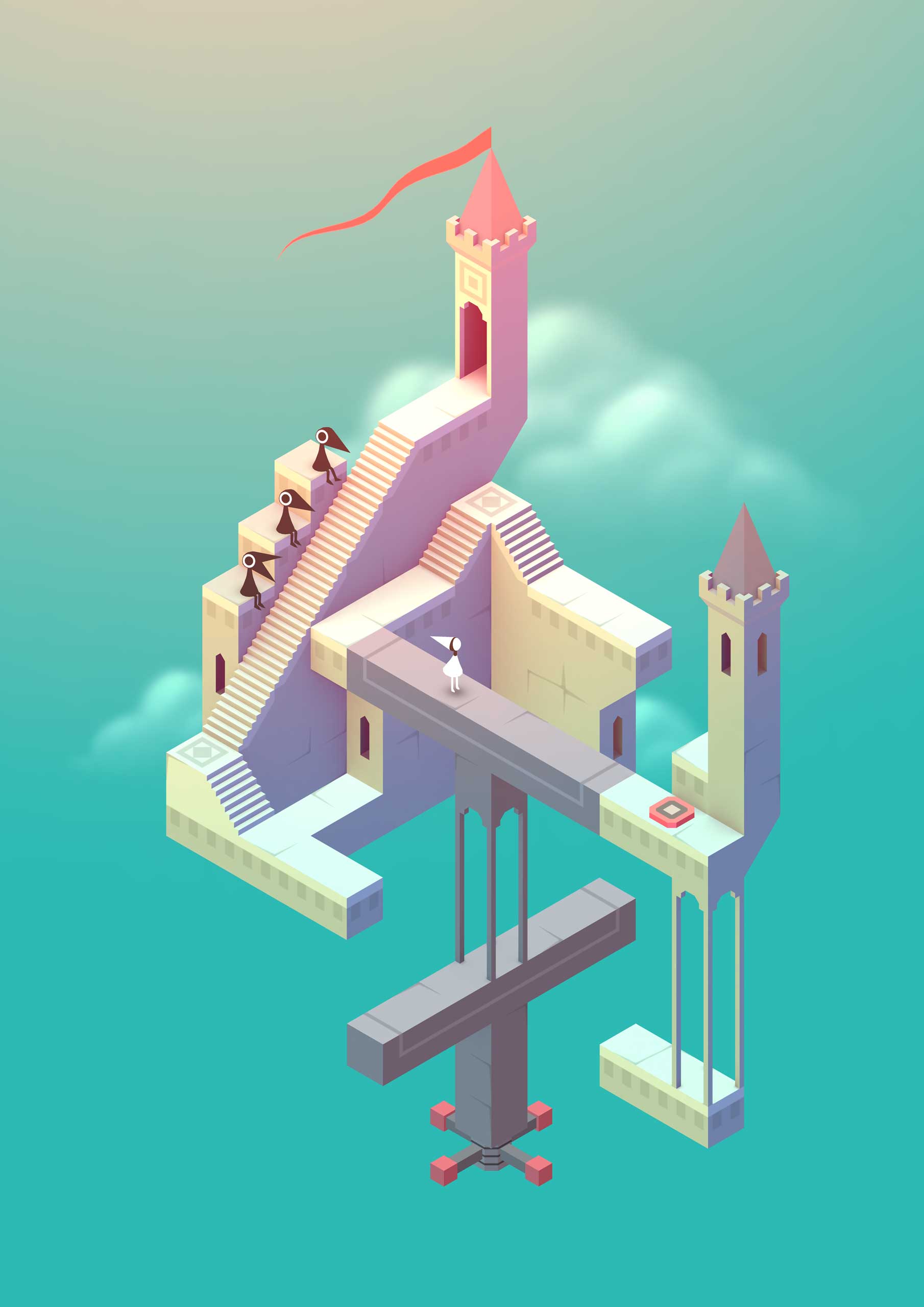

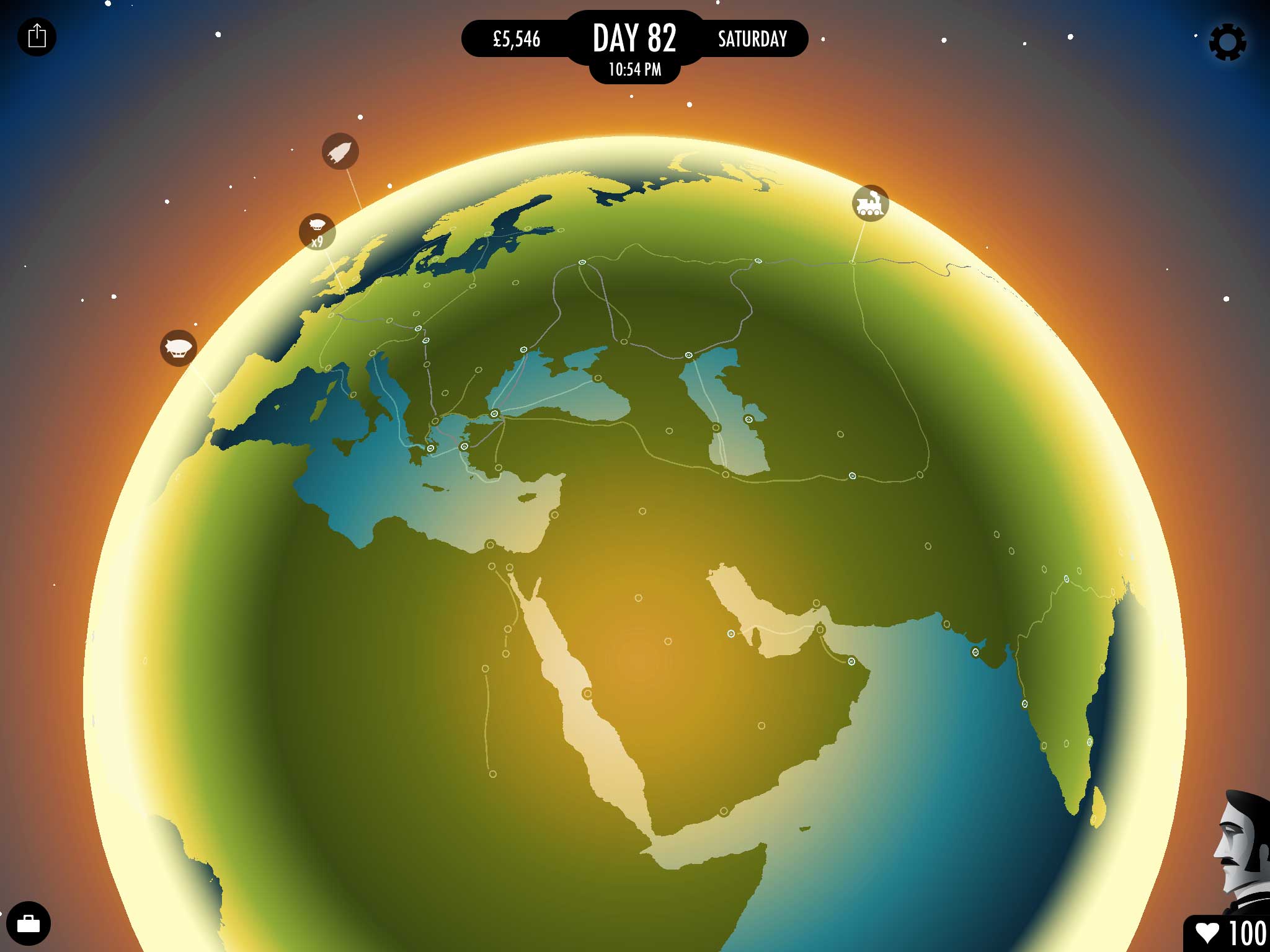

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com