Man can ignore, but never evade, the power of Nature. Reminders of this stark truth might come only intermittently, but when they do arrive it is with irresistible force, displacing the overhanging importance of disease or penury in the dispensation of impersonal destruction. In the face of a muscle-flexing volcano or a tsunami there is no scope to reflect that here might be punishment for personal sin or crime: the good, the bad and the frankly hideous disappear as one. No one can live in knife-edge tension day in day out, however. We all know what happened to the dinosaurs, but it is best to suppress conscious acknowledgement that Nature, if moved to, can annihilate everything just like that.

Such awareness certainly underpinned the psychology of the ancient Babylonians. They were dependent for life on the waters of the paired Tigris and Euphrates of modern-day Iraq but, at the same time, were always vulnerable to seasonal or non-seasonal flooding. On top of that they half-remembered a time, long before writing, when their world had been eclipsed by uncontrollable waters that swept over the flat landscape down to the Persian Gulf. The remotest Mesopotamian history, as constructed by the ancient chroniclers compiling their tablets in cuneiform, was categorized as before, or after, the Flood. A great deluge of ancient Mesopotamia surely happened, never to be forgotten.

For many, the old Bible stories might as well be fairy tales.

That the Flood became a focus for Mesopotamian myth — or what we call myth — is no surprise. The myth, we may argue, is a response to the disaster, incalculably remote at the time of first literary expression, but nevertheless part of unchanging awareness. The pith of the story is of timeless appeal: one hero in the hot seat with full responsibility and almost no time to save the world. The whole is wrapped up in gripping, episodic narrative: planning the flood, choosing the hero, building the ark, surviving the Flood and landing safely on the Mountain to start all over again. The core of the mythologem is that, whatever would happen, the gods would never actually allow the extinction of the human race. And, as for the matching narrative that developed: those who survive floods are those in boats. So, it seems to me, the myth grew up to encapsulate the consoling conviction that, whatever the cosmic disaster, there will always be divine intervention, albeit at the last minute. Man will survive.

Death by water and hair’s-breadth rescue underpins more than one work of Babylonian literature. At the time of lawgiver Hammurabi in the 18th century BC, it was central to the Story of Atra-hasis, the first Babylonian equivalent of our Noah. The gods, irritated by human hubbub, voted in parliament to wipe them out and create a silent race of workers. The Flood was their third attempt and would have had its effect but that the god Enki, humorous, far-sighted and a touch rebellious broke his oath of silence to leak the information to a handpicked individual. This Atra-hasis was to build an Ark, he stipulated, a custom-made life-capsule that would float and keep its precious contents safe. All other life perished, but when the waters subsided and Atra-hasis’s lifeboat came to rest vitality and fertility broke out with renewed vigor. The gods, seduced by sacrifices wafting their way to heaven, professed themselves pleased after all that Enki’s stratagem had been so successful. A millennium later the narrative made up the whole Tablet XI of the classical Epic of Gilgamesh, in which the hero learns personally about the events of the Deluge from the man who survived it, now called Utnapishtim.

In 1872, the Assyriologist George Smith, working in the British Museum in London, was electrified to discover that he was reading an account of the Flood in cuneiform that even in detail paralleled with uncanny familiarity the story of Noah in the Book of Genesis. The discovery, in a world where everyone knew their Bible intimately, caused a furor: how could that iconic Judaeo-Christian-Islamic narrative appear on a clay tablet from far-off Nineveh? The similarity of the accounts was bewildering. And which version, everyone wondered, came first? George Smith’s find dated to the 7th century BC, but other cuneiform tablets and fragments have since come to light; the story goes back at least to the 18th century BC in ancient Mesopotamian culture. Flood narrative in cuneiform thus preceded the Hebrew text of Holy Writ by more than a millennium.

We are told in Babylon that the trigger for destruction by the gods was the unacceptable noise level of mankind. Closer reading suggests a more profound idea under the surface; the first round of creation had overlooked the necessity for barrenness, disease and death, and the real problem was overpopulation, a matter carefully attended to after the Flood. Clearly this human story in all its dramatic power, exemplifying man’s frailty under heaven, was as irresistible to the compilers of Genesis as it remains today even when wrenched out of the context of the Bible. Recycling in Hebrew dress, however, saw the message subtly and crucially altered in line with Old Testament theology: Divine destruction was to punish sin, and Noah was selected for the fateful task of boat-builder on account of his unique uprightness as a moral man.

The Hollywood appeal of the story has been perennially vital, and the latest director to make a play for it, as given out by his film company in 2014, states that his film Noah is true to the essence, values, and integrity of a story that is a cornerstone of faith for millions of people worldwide. Interestingly this carefully worded passport has not led to a secure reception in all quarters, and the film has been already banned in Pakistan, Bahrain, Qatar, and UAE as offending Islamic sensibilities. We shall see what transpires in the box office. There is, however, another dimension.

When planning the exhibition Babylon, Myth and Reality that opened in the British Museum in 2008 my colleagues and I found that one can no longer assume, in Great Britain at least, anything like the widespread familiarity with the text of the Bible that prevailed at the time of Victorian George Smith. A majority of people below the age of 50 in the UK today have assuredly never actually read their Bible. The effect of this process is to divorce the timeless episodes and the characters that populate them from the Great Book whence they emerged. The Tower of Babel, Daniel in the Lion’s Den and the Writing on the Wall are often referred to in conversation, but sundered from understanding that they “really” derive from the Bible: they might as well be fairy tales, Shakespeare or even Hollywood. By now for many young people such characters as Noah or Technicolor Joseph are likely to stem from the same stable as Snow White, Robin Hood or Batman. The full force of cinematographic cum computerised filmmaking applied to the Noah story now can only serve to reinforce this process.

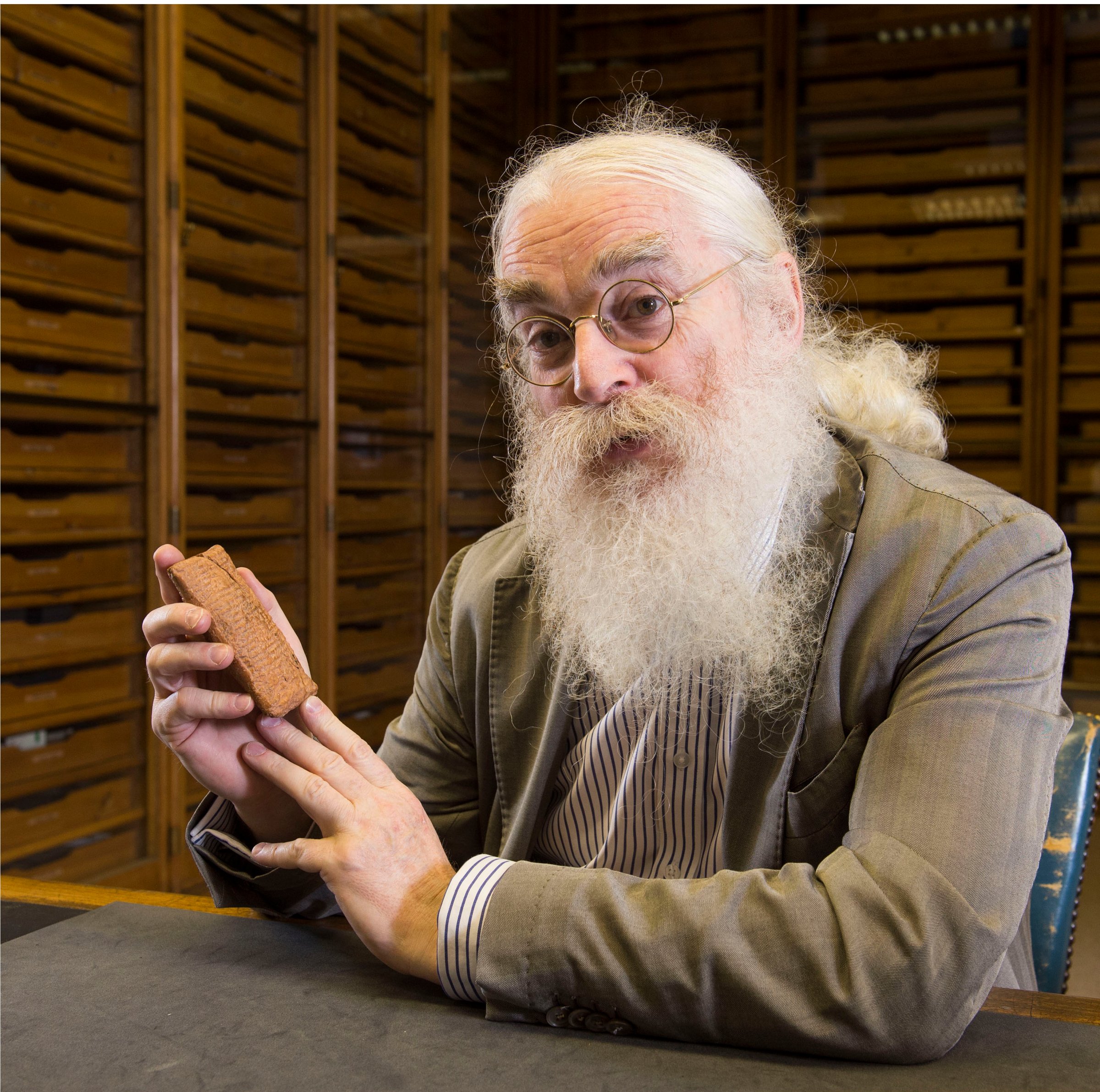

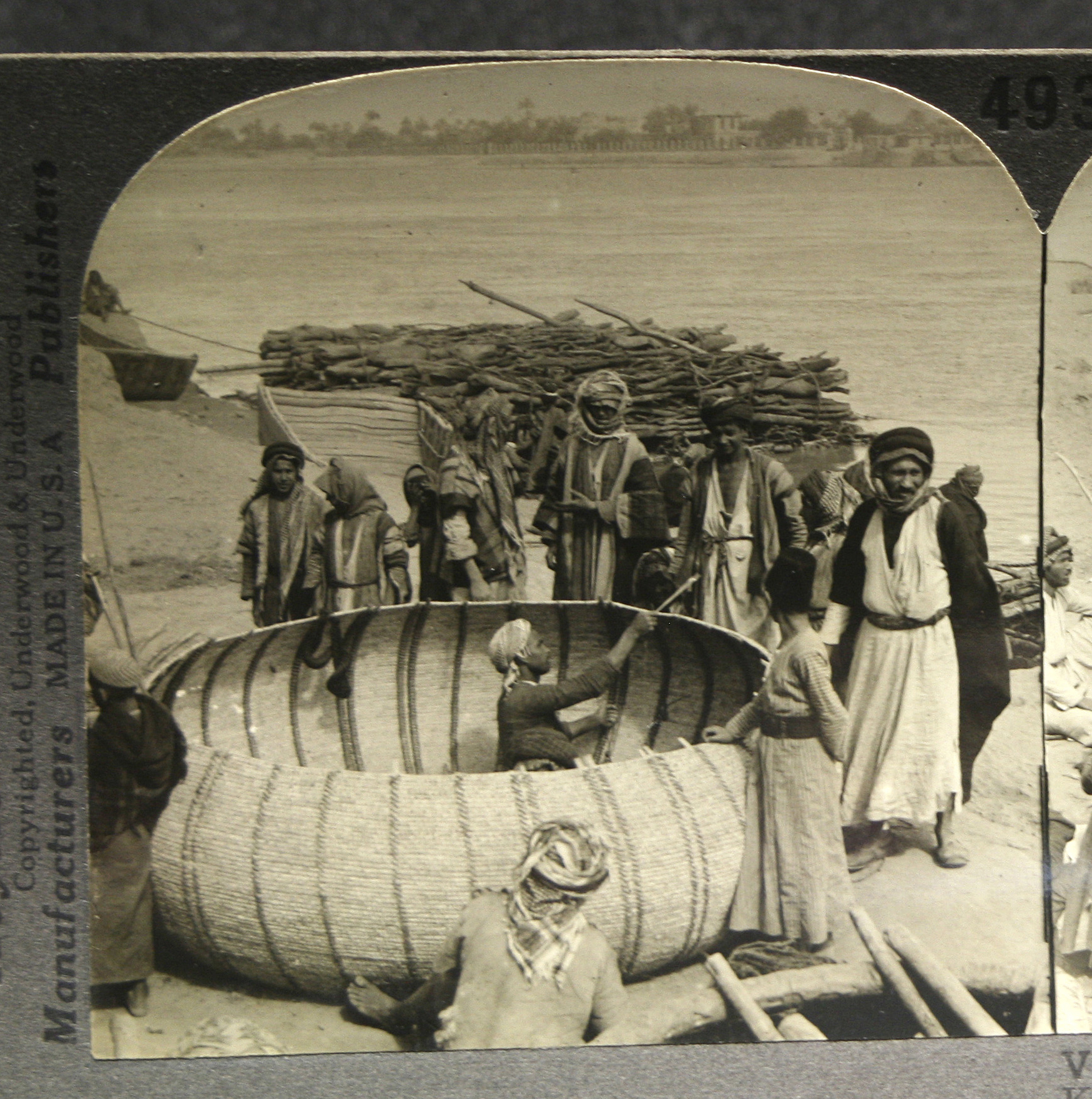

Their professed adherence to the text of Genesis means that Paramount Pictures have followed the Biblical specs as regards shape and proportion. It remains to be seen whether the costly craft launched by Russel Crowe and his ark wrights will sink or swim. Meanwhile backroom work on the cuneiform origins of the Genesis narrative has been proceeding apace. This ancient inheritance has recently been enlarged by a completely unexpected sixty-line Flood Story inscription brought to me at the British Museum for identification. The text tells us for the first time exactly what Atra-hasis’s Ark was to look like: it was round, a giant coracle, made of palm fibre, with wooden ribs, and waterproofed all over with black and sticky bitumen. Here was a plausible vessel that could really do the job for which it was needed: not the multi-floored cubic skyscraper that Utnapishtim described to Gilgamesh, or the awkward, coffin-shaped affair that is presented in the Hebrew text, but a vessel type that really existed. Coracles had plied the Mesopotamian waterways since time immemorial, transporting man and animal in perfect safety, for whatever happened in a coracle it would never sink. Thus for the Babylonian poets of 1750 BC there was only one possibility for the type of boat that Atra-hasis could have relied on to save the world: a traditional coracle, a lot bigger than any that had ever been dreamed of before, but a soundly made and trusty coracle. Perhaps if Hollywood had stuck to the Babylonian script they would not be getting themselves in such hot water today.

Irving Finkel is a curator in the Department of the Middle East at the British Museum in London. His book, The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood is published by Doubleday in New York and Hodder and Stoughton in London.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com