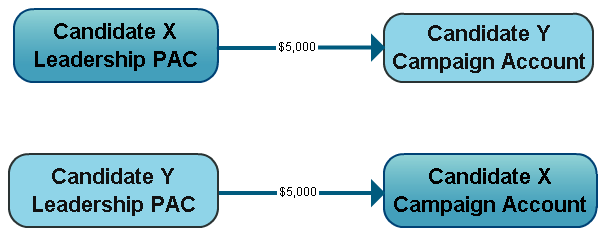

With just a few days remaining in the first quarter of 2014, Mary Landrieu did something generous: The embattled Democratic senator from Louisiana, herself in the midst of an exceedingly tough re-election race, used her leadership PAC to give $5,000 to the campaign of Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), who at the time expected a competitive race of his own and had won in 2008 by just 312 votes.

The contribution from Landrieu’s Jazz PAC came on March 28, three days before the Federal Election Commission’s filing deadline for candidate campaign finance reports, and plumped up Franken’s fundraising numbers — figures that would be seen as an indication of the former Saturday Night Live star’s ability to attract the money he needed to win.

Landrieu’s action looks less altruistic, though, considering what happened next: Franken’s leadership PAC, Midwest Values PAC, gave $5,000 to Landrieu’s campaign on March 31 — the very last day of the reporting cycle. As with Franken’s, Landrieu’s fundraising numbers were goosed just a bit as a result.

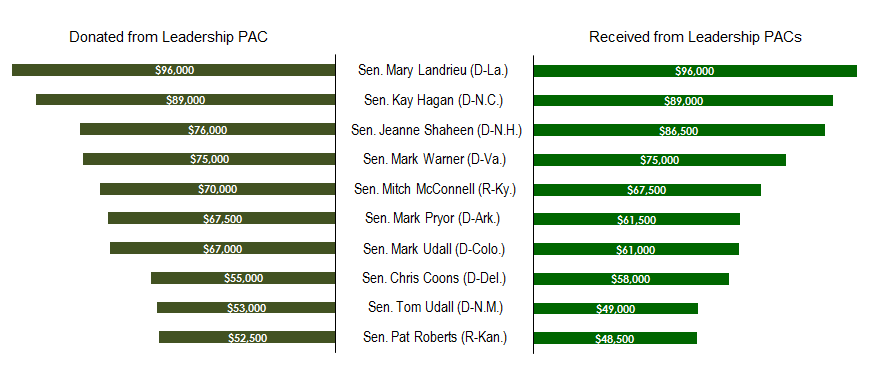

The trade appears to have been no coincidence. Landrieu engaged in 21 such exchanges through Sept. 30 of this midterm election cycle, giving $96,000 from Jazz PAC to other candidates’ campaigns. Within seven days before or after each donation, she received exactly the same amount back from the leadership PACs of those same candidates. Most of the activity occurred shortly before an FEC reporting deadline. Some of the trades happened within the very same day.

Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) has boosted her campaign account by nearly $100,000 using an increasingly popular maneuver involving leadership PACs.

And she’s not the only one. Democratic Sens. Jeanne Shaheen (N.H.), Kay Hagan (N.C.) and Mark Udall (Colo.) also all had at least 20 such swaps, each of which took a week or less to complete. All are in squeaker elections. Other Democrats who had more than 10 transactions: Sens. Franken, Chris Coons (Del.), Jack Reed (R.I.), Jeff Merkley (Ore.), Mark Begich (Alaska), Tom Udall (N.M.), Mark Pryor (Ark.) and Mark Warner (Va.), and Reps. Bruce Braley (Iowa) and Gary Peters (Mich.), both of whom are running for Senate seats.

On the Republican side, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky engaged in 14 of these exchanges, transferring $70,000 out of his Bluegrass Committee PAC to other GOP candidates who then used their PACs to donate $67,500 to his campaign, all within seven days. Sen. Pat Roberts (Kan.) did the same thing 11 times in this cycle using his Preserving America’s Traditions PAC.

In an era of multimillon-dollar donations to outside spending groups, the sums involved here may seem like small potatoes. But for candidates forced to gather contributions under hard-money limits — they can take no more than $2,600 per election from individual donors — every little bit counts. And if the contributions are the larger sums that PACs can give, so much the better. For an indication of how anxious candidates are to scoop up every dollar, look no farther than the desperate emailed fundraising appeals they send out as, each quarter, reporting deadlines approach.

“The totals aren’t huge, but this is an example of the ‘leave no stone unturned’ principle of campaign finance,” said Bob Biersack, senior fellow at the Center for Responsive Politics and a 30-year veteran of the FEC. “This is going to pretty amazing lengths.”

And some think the swaps are little more than an attempt to evade legal limits, since leadership PACs can give no more than $5,000 per election to their own sponsor’s campaign.

“What you’re looking at clearly strikes me as an abuse of leadership PACs that undermines the integrity of basic contribution limits,” said Paul S. Ryan, senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center. The transactions — even though they don’t involve exactly the same dollars circling back to the original donor — could be considered a form of money laundering, he added.

Said another campaign finance lawyer who asked not to be named: “This appears not to be happening by spontaneous combustion.”

Landrieu and the others have also used their leadership PACs to support candidates who did not partner with them in quick-turnaround reciprocal contributions. Her Jazz PAC has given a total of $266,500 to House and Senate Democratic candidates, for example. But a substantial portion of that has come back to her in the form of contributions from the leadership PACs of the recipients of her donations.

Neither Landrieu’s campaign press office nor the campaign’s attorney responded to multiple requests for comment.

These are the top 2014 cycle practitioners of exchanges within one week, through Sept. 30:

Building goodwill — and more

Leadership PACs date back to the late 1970s, when Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.) set one up, with a nod from the FEC, and used it to win the chairmanship of the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Health by giving out tens of thousands of dollars to his committee colleagues. This cycle, with Waxman retiring, two lawmakers who want to fill his slot as the top-ranking Democrat on Energy and Commerce are using their PACs to woo support from other members of the panel.

And supporting endangered members of their own party is certainly another way that lawmakers use these structures. Landrieu has hauled in more leadership PAC money than any other candidate this cycle, receiving a total of $446,500. Also among the top 10 are Pryor, Hagan, Warner, Shaheen and Mark Udall — all Senate Democrats whose re-election bids are no walk in the park. Below are the top 10 recipients of leadership PAC funds this cycle:

The win-friends-and-influence-people model of the leadership PAC isn’t always the one that’s followed, though. In fact, there are few restrictions on how a leadership PAC’s sponsor can spend its cash. Sometimes they’re used as little more than slush funds, taking in contributions of up to $5,000 per year from lobbyists and special interests who have already maxed out to a lawmaker’s campaign committee and spending the money on travel, greens fees or nice meals for that same lawmaker – at times in the company of the very interests that donated the loot in the first place.

Most leadership PACs don’t donate to their own sponsor’s campaigns. That may be because, even though they may do so within the limits, the FEC hasn’t made the rules easy to discern. Sen. Thad Cochran (R-Miss.) is one of the few senators to have done so in the 2014 cycle, and he did it big, giving his campaign the maximum $5,000 permitted for each of his races: primary, general and — a special circumstance — his primary runoff contest. He sent another $5,000 to his legal fund to help fight his primary opponent’s challenge to Cochran’s victory.

Other than those outright, strictly limited donations, though, campaign activities can’t be paid for by a candidate’s PAC. According to the FEC, a leadership PAC financed and controlled by a candidate or officeholder is “neither an authorized [campaign] committee nor affiliated with the candidate’s authorized committee.”

But the swaps appear to be a way to work around the limits. “The net effect is to turn leadership PAC money into campaign money, campaign finance lawyer Kenneth Gross, a former head of the FEC’s enforcement division.

More money each cycle

In this election cycle, 531 leadership PACs — most of them associated with current lawmakers but some linked to former members or candidates — have raised a total of $144.7 million, giving about 36 percent of it, or $52.4 million, to candidates and party committees.

As leadership PAC wealth has grown with every election cycle, so has the rate of short-term exchanges between candidates. During the 2008 cycle, 32 candidates made a total of 71 trades that were completed within seven days. So far this cycle 170 of them have occurred among 56 candidates.

The amount of money changing hands has increased sharply over the past four elections cycles as well — growing from $674,400 in 2008 to $1.28 million so far this cycle. The 2014 number expands to $1.7 million when the lens is widened to look at exchanges within 30 days, rather than seven. But the overwhelming number of such round trips — 75 percent of the ones that occurred within 30 days — have happened within a week.

While more candidates, 92, conducted these exchanges during the 2012 cycle, this cycle’s top traders appear to have perfected the process. Prior to the 2014 races, no candidate made such an exchange more than 14 times. There’s also more money involved this time; the 2012 total was $1.07 million.

Senate Democrats seem to have dominated the practice this cycle, but during the 2010 midterms it was GOP Senate candidates making the majority of short-term exchanges. Sens. Chuck Grassley (Iowa), Johnny Isakson (Ga.), Richard Burr (N.C.) and John Thune (S.D.) topped the list as the Republicans picked up six seats in that election.

Same-day turnarounds

Democrat Coons is not in a competitive race, but he has been party to 18 transactions with a round trip time of less than seven days during this cycle — shelling out $55,000 from his Blue Hen PAC and receiving $58,000 in return.

When reached for comment, Coons’ campaign dismissed the possibility of quid pro quo.

“Senator Coons has supported Democratic candidates, including a number of his colleagues in the Senate, through his campaign account and leadership PAC,” campaign spokesman Jesse Chadderdon said in an email. “Many of his colleagues have been supportive of his re-election campaign as well. Whether or not another candidate has supported him or will support him down the road just isn’t part of the evaluation process. It’s about helping the best people win difficult elections.”

Democratic Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire has the most single-day turnarounds of leadership PAC exchanges.

Even though it’s not surprising to see candidates showing good will for their party colleagues by way of their checkbooks, this explanation seems to fall short of clarifying exchanges made between candidates in the same 24 hour span.

During the 2014 election cycle, candidates have traded leadership PAC funds for campaign cash on the same day 37 times using this mechanism; 28 of them involved the exact same amount coming and going. The sum exchanged most frequently was the maximum allowable $5,000, though lesser amounts that nevertheless matched up also went back and forth.

Shaheen is the leader in this category, sending money from her A New Direction PAC to colleagues’ campaign coffers and receiving leadership PAC checks in her campaign account on the same day on eight occasions. On June 24 of this year alone, Shaheen managed to complete this cycle twice — with Coons and Reed.

Her campaign did not respond to OpenSecrets Blog’s request for a comment or explanation of the acitvity. Nor did more than a dozen other campaigns that were called and emailed.

Several campaign finance experts we asked about the pattern of activity mentioned former House Majority Leader Tom DeLay’s (R-Texas) conviction for taking corporate contributions raised by a state-level PAC and sending them through the Republican National Committee, which then contributed to state candidates named on a list that was given to the national group along with the money; Texas law prohibits corporate money from going to candidates, and the GOP leader was charged with money laundering. His conviction was ultimately overturned.

While the leadership PAC exchanges differ in many ways from the activity DeLay orchestrated, the transactions similarly feature attempts to replicate the peculiar talents of the fairy-tale Rumpelstiltskin.

“Moving money around to try to change it from cash that isn’t useful, into cash that is, has always been part of the fundraising game,” said Biersack. But the leadership PAC-to-campaign committee swaps, he said, are “an illustration of how to game the system in every conceivable way.”

Center for Responsive Politics researcher Andrew Mayersohn contributed to this story.

The Center for Responsive Politics is a nonpartisan research group focused on money in politics.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com