This week brings the debut of ABC’s Marvel’s Agent Carter, an action series starring Hayley Atwell as a woman who’s underestimated by her male colleagues despite her incredible acumen as a spy. It’s a period piece, set in the 1940s, but one hardly needs to look back that far to find women on TV whose strength in the workplace and self-confidence defined them and befuddled critics.

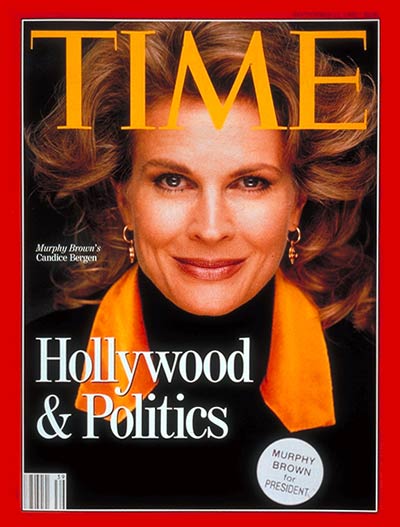

Murphy Brown, the hardworking, single title character of a CBS sitcom starring Candice Bergen and the subject of a 1992 TIME cover, had been on-air for three seasons when, in 1991, she discovered she was pregnant and decided to keep the baby. It was a predicament not just for the character but for a TV show that, though unafraid of political controversy, was now going far beyond traditional parameters. TIME compared Bergen’s character to Lucille Ball’s on I Love Lucy after Murphy decided to keep the baby: “And to think, Lucy couldn’t even say pregnant on TV.” Even despite the electoral gains by women in the Senate that got 1992 dubbed “the Year of the Woman,” Brown may have been the most-talked-about female political figure of the year.

Murphy Brown’s televised pregnancy and her decision to raise her child as a single mother were a flashpoint in the 1992 election — and changed the role of women on TV. Today, from Scandal to The Good Wife, TV’s packed with strong and complex female characters; thanks, Murphy! Though Murphy Brown is rarely watched or invoked today, the high point of its relevance made a lasting impact on the way we talk about television, and about motherhood.

The show had made waves in the years before Murphy Brown’s pregnancy with, as TIME critic Richard Zoglin put it in May 1992, “the smarts and the moxie to take pokes at everything from gossip-mongering tabloids to the Anita Hill hearings.” Bergen’s character, a recovering alcoholic working for a Washington-based TV news magazine show, was unafraid to be unlikable; the show, and its dependence on sharp, pop-culture-centric comebacks, struck Zoglin as “cleverly written, but in a smug, soulless, metallic way.”

Viewers disagreed. Murphy Brown went into its big fourth-season pregnancy plot line in the Nielsen ratings top ten and with a shelf full of Emmys, including one for best comedy and two for Bergen’s performance. But while viewers and critics were accustomed to the show’s sharply political tone and its acidity, the pregnancy plot touched upon a third rail of sorts. The show foregrounded the question of working motherhood, with a fictional baby shower for Murphy attended by real-world TV news stars from Katie Couric to Joan Lunden. It was a pointed argument that work-life balance was possible (though Zoglin hastened to point out, in his May 1992 take, that more serious journalists like Diane Sawyer, the ones “who Murphy is really modeled after,” skipped the shower).

The fourth season ended with the birth of baby boy Avery — but the controversy was only beginning.

In a May 1992 speech about the breakdown of the American family in San Francisco, Vice President Dan Quayle decried Murphy Brown’s decision to raise her child alone: “It doesn’t help matters when prime-time TV has Murphy Brown — a character who supposedly epitomizes today’s intelligent, highly paid professional woman — mocking the importance of fathers by bearing a child alone and calling it just another ‘life-style choice.’”

Quayle came in for more criticism from Hollywood — and from TIME. Zoglin characterized the treatment of the incumbent veep, up for re-election, at the 1992 Emmy Awards as “a Rodney King beating by the Hollywood elite,” noting that Bergen thanked Quayle sarcastically in her third best actress speech. The show’s creator, Diane English, told TIME that Murphy Brown was “a liberal Democrat because in fact that’s what I am” and lead actress Bergen described Quayle as “Bush’s buffoon” in the TIME cover package.

But this sort of rhetoric was nothing new: Earlier that year, President George H.W. Bush had urged American families to be “a lot more like the Waltons and a lot less like the Simpsons.” But even The Simpsons were, at the end of each episode, a traditional nuclear family; they even went to church. Murphy Brown was making a reproductive and family decision that stood in opposition to far more than mere matters of taste: As Zoglin pointed out in a June 1992 piece responding to Quayle’s complaint, “prime-time TV these days is boosting family values more aggressively than it has in decades,” citing everything from Home Improvement to Roseanne. It turned out that Murphy Brown was worth highlighting in a Vice-Presidential speech not because it represented the state of television and the culture in general but because, in the particulars of Murphy’s choice, it was so far outside the mores of its day.

But — in a twist that did not go unremarked-upon at the time — once one got past the specifics of how baby Avery came into the world, Murphy Brown was not so outside the mainstream at all. It was a show that followed the vogue at the time in portraying the family bond, however one found it, as an ideal. “It took a Top 10 network series that will undoubtedly be around for years to grab the Vice President’s attention,” wrote Zoglin. “Now he needs to do some channel switching.”

There’s no question that Murphy Brown was attention-grabbing — but, decades later, the show is markedly absent from much of the discussion about great television of the ’80s and ’90s. Perhaps it was the ties to Quayle, and to Bush I-era Republicanism, that spelled a slow death for Murphy Brown, a show whose central mother-son relationship, after all, was as life-affirming as anything on Home Improvement. The show was hardly in immediate danger of cancellation. And yet Quayle’s speech, which TIME columnist Michael Kinsley called in 1994 “the best-remembered speech of the Bush presidency” may well have consigned Murphy Brown to be remembered within the context of the Bush presidency. The show lost some heat off its fastball once the President and Vice President left office in the middle of the fifth season. Every subsequent season fell lower and lower in the ratings — not shocking for a long-running TV series, but proof positive, perhaps, that Murphy Brown’s formula of explicit political discourse, something the series indulged more and more post-baby, was a turn-off for some.

It’s hard for pathbreakers. By the time it left the air, Murphy Brown was a footnote. But two months after its cancellation, Calista Flockhart appeared on the cover of TIME in service of her character Ally McBeal, a single woman whose pursuit of a career hardly stood in the way of her desire to be a mother. Indeed, Ally’s biological clock was the very text of Ally McBeal. And two years after that, the women of Sex and the City would be on TIME’s cover, asking “Who Needs a Husband?” (Soon enough, cover subject Cynthia Nixon’s character Miranda would carry a baby to term without the intention of getting married.) Today, the (anti?-)heroines of Scandal and How to Get Away With Murder define themselves through their acuity at work, with the biological clock left entirely aside; Claire Underwood of House of Cards is the most fascinating character, male or female, on television, and one whose decision not to have a child is presented matter-of-factly and with little agonization.

Neither Ally McBeal nor Sex and the City – nor Desperate Housewives, whose star, Teri Hatcher, played a single mother and appeared on TIME’s cover in 2005– would end up becoming political talking points the way Murphy had. Carrie Bradshaw is the one who still makes news, but someone had to blaze a trail. Later series just learned that specific political references burn quickly – and benefited from Bergen’s character going through a political maelstrom so none of them had to.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com