At least 29 donors have given $1 million or more to state-level campaigns so far this election, with a dozen of the big givers made up of self-funding candidates, according to an analysis of campaign finance data.

The other big donors to state campaigns in the 2014 election include billionaires, corporate giants, unions and nonprofit political groups. Each donor has shelled out more than 19 times the country’s median household income.

According to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of state records collected by the nonpartisan National Institute on Money in State Politics, top donors include:

The analysis is preliminary — the totals will only go up as more contribution reports are filed in the states. In addition, the National Institute is still processing reports that have already come in. Less than 80 percent of those reports have been processed thus far this election cycle. Rauner (*) alone, for example, has given at least $12 million more for a total of $26 million, state records show.

Despite those limitations, the Center still identified at least 29 of these million-dollar donors who have given more than $84 million out of the more than $1 billion in the two-year, 2014 election cycle. The Center looked at reports processed by the National Institute through Oct. 29.

While the race for U.S. Senate has grabbed most of the national election headlines this year, much of the action is at the state level. Thirty-six governorships are on the ballot in addition to more than 200 other statewide races and thousands of statehouse contests.

And unlike at the federal level, some states allow unlimited contributions to candidates. In addition, several states also allow direct contributions from the treasuries of corporations and unions.

Seeding their own chances

Rauner, Wolf and Jones are just three of at least 12 candidates for state-level office who have poured at least $1 million into their own campaigns.

States can limit contributions to candidates, but there are no such limitations on how much a candidate can give to his or her own campaign. That gives wealthy individuals with political aspirations an advantage over less wealthy opponents, said Bill Rosenberg, a political science professor at Drexel University.

“If an individual wants to run for public office, and they can be self-financed and the parties view them as reasonable candidates,” Rosenberg said, “a lot of times the party will just step out of the way because they can take those financial resources and put them into other races.”

In the case of Rauner, his early contributions to his campaign may have helped him attract even more cash to his joint campaign with running mate Evelyn Sanguinetti, including at least $4.5 million from Griffin and $7 million from the Republican Governors Association.

“The millions reassured prospective donors that the Republican Party wasn’t going to have a flash in the pan here, that he was going to be in until the end, that he wasn’t going to get outspent,” said Brian Gaines, a political science professor at the University of Illinois.

Limitations on influence

But other donors who give directly to candidates often face strict limits.

In 21 states, corporations cannot give money to candidates’ campaigns, and 16 states ban unions from giving, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. (Unions and corporations can give through their political action committees, though contributions may be limited.)

Thirty-eight states cap the amount a person or group can give to a single candidate.

And until recently, donors in more than a dozen states were limited in how much money they could give overall in an election cycle. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down aggregate limits at the federal level in April, with its ruling in McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission. States such as Connecticut and Wisconsin have pledged to not enforce the limits in state elections this year.

It’s not yet clear how far-reaching the impact of the decision may be on this election. Still, the existing contribution limits largely shape the way money pours into elections.

The two states seeing the highest number of donations to candidates from the mega-donors so far are Texas, where individuals and political action committees can give candidates as much as they want, and Illinois, whose governor’s race allows unlimited contributions this cycle.

Six-figure donations are the norm in marquee races in Texas.

This cycle, Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott, a Republican running for governor, received at least $900,000 from Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons, who died in December 2013. Energy tycoon Kelcy Warren has given Abbott at least $450,000, while telecommunications executive Kenny Troutt along with his wife, Lisa, has given him at least $350,000.

Such large-scale giving does not carry a stigma in Texas of trying to buy access, according to Mark P. Jones, a political science professor at Rice University in Houston. Instead, he said, it is “simply par for the course” in the Lone Star State.

“Large donations have little to no political blowback,” Jones said.

Under Illinois rules, if a candidate for statewide office contributes more than $250,000 to his or her own campaign, or if an outside group spends that amount supporting a candidate in the race, caps for contributions to a single candidate are thrown out in that race.

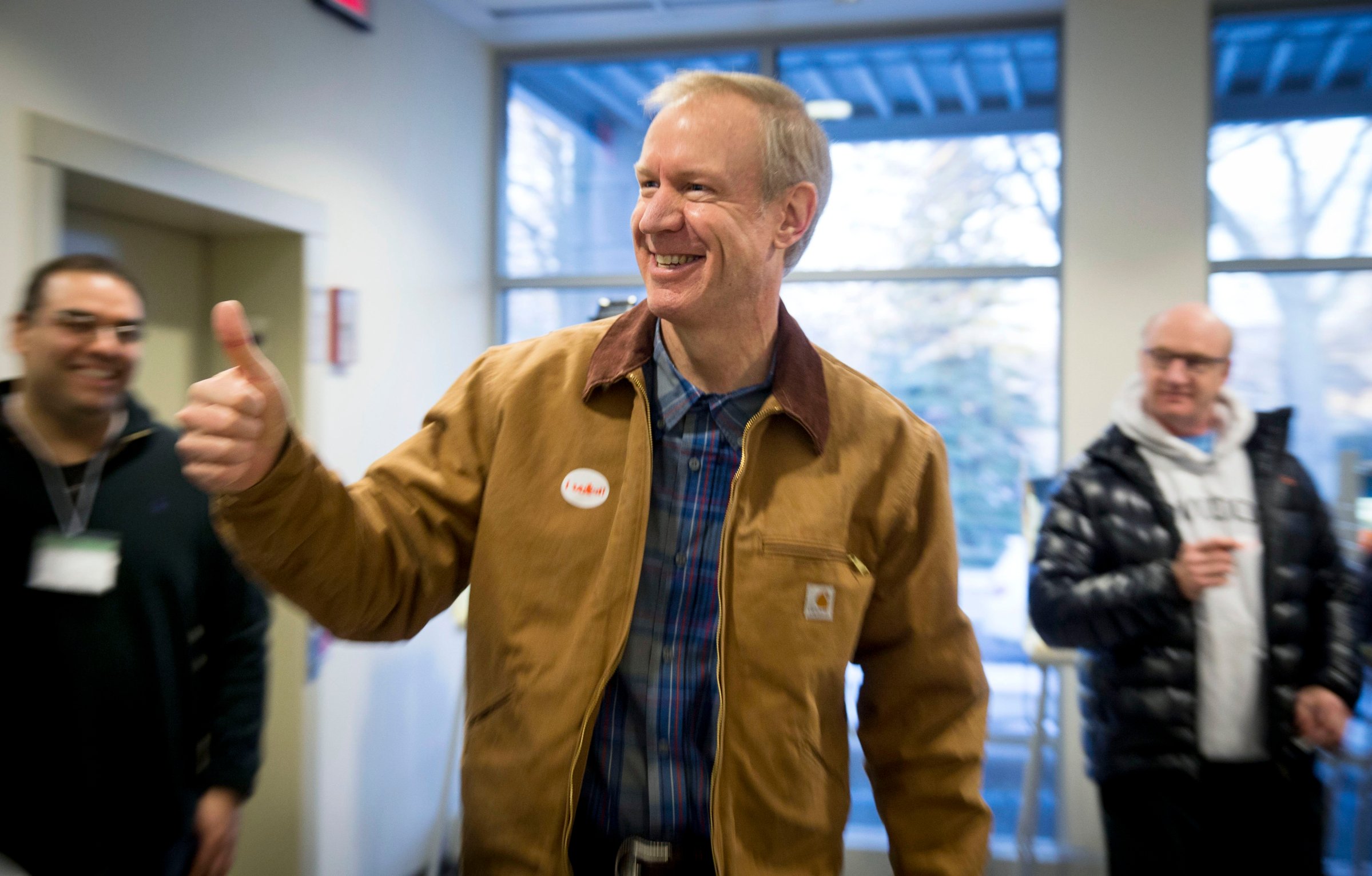

At first Rauner, the Republican gubernatorial candidate, avoided giving his opponent the chance for limitless fundraising by injecting $249,000, just below the threshold, into his campaign in March 2013.

But before the end of that year, Rauner gave his campaign another $1 million, pulling the plug on caps in the race. By now, the Republican nominee has contributed more than $26 million of his own money to his campaign, according to Illinois campaign finance records.

Rauner’s campaign did not respond to the Center’s request for comment.

His self-funding also cleared the path for incumbent Gov. Pat Quinn and his running mate to accept more than $3.6 million from the Democratic Governors Association, more than $755,000 from Chicago media mogul Fred Eychaner and millions from unions, including more than $1.2 million from a branch of the Service Employees International Union.

Getting around the limits

Even in states with contribution restrictions, well-heeled donors have found ways to give generously — and legally — to the candidates they favor.

In Pennsylvania, for example, corporations and unions can’t give directly to candidates, but they can give unlimited amounts of money if they establish a political action committee in the organization’s name. That’s how the Pennsylvania State Education Association, a state teachers union, gave $500,000 to Wolf’s gubernatorial campaign.

In New York, wealthy individuals can donate through multiple limited liability corporations to dodge the state’s $60,800 per cycle contribution limit for such businesses. Real estate magnate Leonard Litwin, for example, has given at least $1 million to Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo using this method, according to a recent report by the New York Public Interest Research Group. The original sources of such contributions, though, are not reflected in the National Institute on Money in State Politics’ data.

A representative for Litwin did not respond to requests for comment.

Sometimes the best way around the rules is to avoid them altogether by giving to independent groups instead of candidate campaigns. Thanks to the 2010 Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, and subsequent rulings, there is no limit to what a person, corporation or union can give to independently acting political organizations.

The tactic is widespread this election. Roughly a fifth of the television ads airing in state-level races this cycle were paid for by groups that operate independently from candidates’ official campaigns, according to a Center for Public Integrity analysis of data from media tracking firm Kantar Media/CMAG.

But many donors this cycle have given directly to candidates and helped fund outside political efforts beyond state-level races.

Eychaner, for example, may not make a list of million-dollar donors to candidates for state-level office this election. He has so far given at least $755,000 to Quinn in Illinois. But he has also given about $8 million to federal super PACs this year, according to the Federal Election Commission. In 2012, he was the largest Democratic donor to independent spending groups, having given $14 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

A representative for Eychaner declined to comment.

On the other side, Griffin was one of the five largest donors to the Washington, D.C.-based Republican Governors Association in the first nine months of this year, according to the group’s latest tax filing.

A representative for Griffin declined to comment.

Why do they give?

For individual donors, there are several likely reasons why they may give to candidates’ campaigns, said Loyola Law School Professor Justin Levitt.

For some, political ideology is a motivating factor, Levitt said. For others, large contributions are a way for donors to thrust themselves into the public consciousness. Still others are looking to gain favor with the people who could end up regulating their business interests. Sometimes, it’s a combination of the three.

Though some corporations are ideologically motivated, most businesses’ political donations are effectively “bet hedging,” he said.

Cable television giant Comcast Corp. parceled out at least $1.2 million in donations to candidates for state-level office in 36 states, often with as little as $100 given to the campaign of a legislative candidate.

“We believe that it’s important to be involved in the political process,” said Comcast spokeswoman Sena Fitzmaurice. “There are probably thousands of bills and regulatory state actions every year that affect the company.”

Fitzmaurice said the company tends to give across party lines and mostly to incumbents.

The company gave to Democrats in 28 states, Republicans in 31 states and at least one independent in Alabama, the Center’s analysis shows.

Where the company directs its political donations could depend on factors such as whether an election could shift party control of a state legislature or whether a state is considering regulatory action, Fitzmaurice said.

“For a corporation, making a donation may well be laying a bed of good will for legislators or regulators down the line, either to prevent unfavorable legislation or to try and get favorable legislation,” Levitt said. “It’s not uncommon at all for legislators, at least, to do a mental check of whether they’ve received a contribution before they decide exactly how badly they want to schedule a particular meeting.”

Liz Essley Whyte contributed to this report.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com