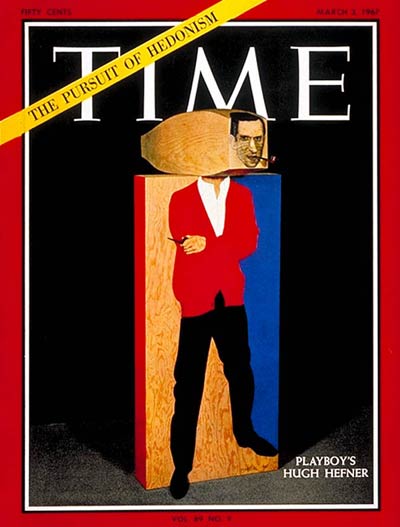

The ’60s had been a hell of a decade for Hugh Hefner and Playboy. By 1967, the magazine had gold-plated contributors like Vladimir Nabokov, James Baldwin and Ray Bradbury; a booming circulation of 4 million; and, to a remarkable degree, mainstream acceptance. The apotheosis of such broad welcome, perhaps, was the appearance of Hefner—or, rather, his cardigan-wearing, pipe-smoking statue equivalent—on TIME’s March 3 cover. In the upper left corner, over a yellow stripe partially obscuring the magazine’s T and I, are the words “THE PURSUIT OF HEDONISM.”

It had been nearly 11 years since TIME first noticed Hefner and his creation. Back then, in 1956, the nearly three-year-old magazine was a mere “sassy newcomer,” worthy of only a brief, admiring profile.

A decade later, when contributing editor Edwin G. Warner checked in with Hefner, Playboy Enterprises was a full-on publishing force:

[Hefner] operates 16 Playboy Clubs. He has opened a Caribbean Playboy resort in Jamaica and has started construction of a $9,000,000 year-round resort near Lake Geneva, Wis. Last year “HMH” enterprises sold $2,400,000 worth of products, ranging from tie clasps bearing the bunny insigne to bunny tail wall plaques.

Hefner has also experienced some commercial failures, including Show Business Illustrated, which folded after nine issues with an estimated loss of $2,000,000, and Trump, a Mad-like humor magazine. On the other hand, the newly formed Playboy Press is thriving; last year, it sold $1,000,000 worth of books, most of them containing reprints from the magazine. At present, Playboy’s staff is moving into larger quarters in Chicago’s venerable Palmolive Building, leased for 63 years for $2,700,000. Thanks to eager press-agents, the building’s famed beacon, whose beam can be seen 500 miles away, has been renamed the Bunny Beacon.

Even despite that power, the idea that a mainstream publication—compared to Playboy at least—saw fit to put Hefner on the cover was surprisingly affecting, at least to one person: Hefner himself. Decades later, he recalls that the story meant something on a personal level. “My family subscribed to TIME and then LIFE,” he says. “Those were actually the magazines of record in my home.” (I interviewed Hefner once before, in 2003, on the occasion of an auction of Playboy Enterprises memorabilia, and spoke to him again recently.)

“Making the cover was a big deal. It was a very important moment in my life,” says Hefner. “The 1960s was a big deal in general for Playboy. Playboy really took off like a rocket.” Indeed, by 1972, the magazine’s circulation peaked at more than 7 million.

The TIME story, which clocks in at nearly 5,000 words, is delightful. It’s also somewhat shocking for containing copy and photos that almost certainly would not appear in the magazine today [Confirmed: the print magazine has a very strict nudity policy, and there’s a reason you’re not seeing those photos here, either. –Ed.] On page 81 is a photo of Playboy “Bunnies” sunbathing, in which one can clearly see breasts and buttocks.

The caption: “Young, pouty types without excess intelligence.”

Midway through the story, Art Paul (Playboy’s art director) and Hefner choose photos for the “Playmates-of-the-year” feature:

Paul: This is the best shot of her face.

Hef: That shot makes the girl look too Hollywoodish. She doesn’t look natural.

Paul: Don’t her breasts look somewhat distorted? … It looks as if the shots were made on a foggy day. We don’t want to mix the reader up. You can’t really be sure that this is the same girl.

Hef (viewing new layout): There is something wrong with the angle of that shot. Her thighs and hips look awkward. This doesn’t do her justice . . . There must be other aspects to her personality.

I told Hefner I was surprised Warner had been given such access, particularly since, as a magazine man himself, he’d know that opening the kimono to a reporter is always a risk. “I, from time to time—when I trust people—will give them access to the workings of how we did what we do,” he said. Naturally, though, he casts a critical eye on the resulting story. “I think it is understandable that someone would be more critical of [a story about] something that they really know about,” he said. “I’m pleasantly surprised when they get it right.”

The statue that graces the cover, by Marisol Escobar, now sits in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution. “I thought it was very classy,” said Hefner. “At the same time, I would have liked to have an actual photograph. I’m so cute!”

Read the 1967 cover story, here in the archives: Think Clean

Elon Green is a freelance writer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com