Jennifer Moses is a writer and painter. www.JenniferAnneMosesArts.com

Maybe if I didn’t live so close to New York, or if I weren’t Jewish, or if I didn’t have a son who served in the Israeli Army, or if I myself didn’t travel to Israel regularly, I wouldn’t have even noticed the recent hue-and-cry over the Metropolitan Opera’s production of “The Death of Klinghoffer.”

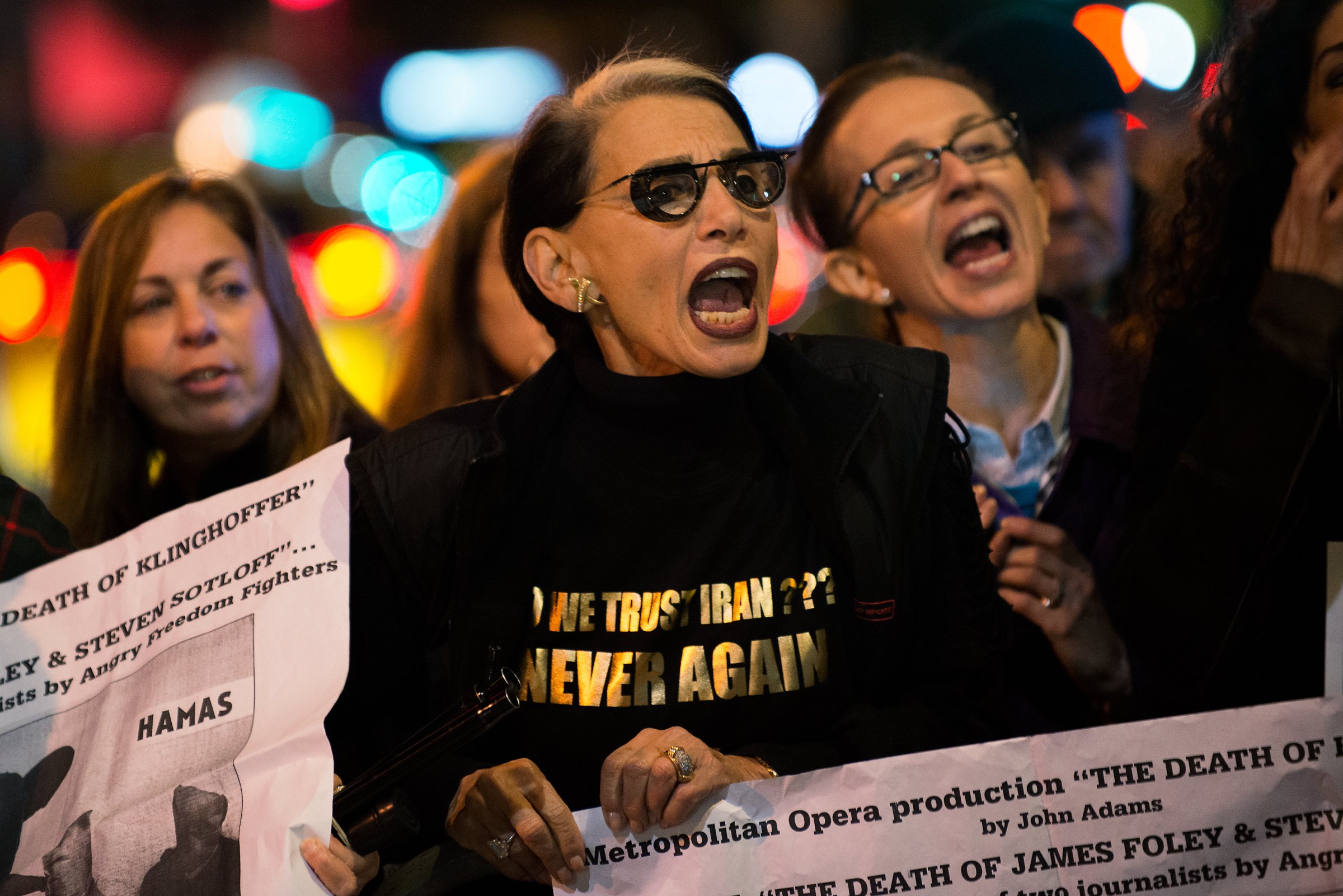

The opera tells the story of Leon Klinghoffer, a Jewish, wheelchair-bound, 69-year-old New Yorker who was murdered by Palestinian terrorists during the hijacking of the passenger ship Achille Lauro in 1985. First performed in 1991, “The Death of Klinghoffer” has from the beginning drawn its share of objections by those who believe its sentiments are both anti-Semitic and pro-extremist. The current production, at the Met, was met with months of grievances, including threats, culminating in a crowd of protesters—some in wheelchairs, others shouting “Shame” and “Terror is not Art” or holding signs linking Peter Gelb, the Met’s general manager, with terrorism—at Lincoln Center on opening night Monday.

The storm of protest swirling around “The Death of Klinghoffer” reminds me of the mini-gust that met the opening of the recent (extremely entertaining) movie Gone Girl. In this case, feminist critics were disturbed by the depiction of the movie’s anti-heroine, Amy Dunne, who is a flat-out psychopath. Or maybe she’s a sociopath. In any event, she’s a scheming, manipulative and extremely pretty b**ch, who on top of her many other sins cries rape when no rape has occurred. The anti Gone Girl folks argued that Amy is a big fat present for misogynists who want to turn the clock back on women’s rights. Really? Because I thought she was a made-up character in a slick, sly, slightly jarring celluloid fantasy.

Let the show go on! The players play! The singers sing! Why? Because censorship is not only an anti-democratic value, but an anti-Jewish one as well. It’s not for nothing that Jews are called the “People of the Book,” so given to debate and argument that there is an old joke that spins out all the variations in which two Jews tend to voice at least three opinions. As bad as censorship is for art, it’s even worse for democratic impulses, equality and the free exchange of ideas. And if you don’t believe me, let’s embark on a quickie review.

Long before Hitler and his BFFs came up with the Final Solution, they started burning books, closing nightspots, banning music not deemed sufficiently German and even shut down the premiere of the movie All Quiet on the Western Front, beating up a few movie fans for good measure. Jews were purged from orchestras and the work of Jewish composers such as Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer was banned. In 1960 in the Soviet Union, once the birthplace of world-shattering works of music, art, ballet and literature, the staggeringly brilliant Jewish Ukrainian novelist Vasily Grossman submitted his masterpiece Life and Fate for potential publication, only to be met by a KGB raid and the seizure of his manuscripts, notebooks and even typewriter ribbons. (The book survived because a friend smuggled a surviving copy out of the country.) Under Stalin, the only music that could be produced or performed had to conform to notions of socialist realism that celebrated the proletariat paradise and glorified its Great Leader. And under the Taliban—well, by now pretty much everyone has heard of Malala Yousafzai.

But America isn’t Pakistan, you rightly say. No gulags here. But that only begs the point. Because even (and perhaps especially) in the United States we’ve got cuckoos of all stripes and affiliations who are absolutely certain that their objections to whatever they’re objecting to in art is both noble and just. J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye has been banned so often it ought to get a gold medal. Ditto Our Bodies, Ourselves (who knew?), Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and perhaps most famously, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. As recently as 1996, Moby Dick was banned from school reading lists in Texas. And lest you think Moby Dick issues were just so late 20th century, as recently as last year members of the South Carolina House of Representatives voted to cut funding at the College of Charleston if it kept Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home on its summer reading list for incoming freshman

There are two issues of great importance at stake here. The first—the obvious one—is that in a democracy, artists must be at liberty to make art as they see fit (see: the First Amendment). But the second is equally important, and that’s the value of art, and any single work of art, to the society in which it appears, and to humanity in general. Is “The Death of Klinghoffer” a good opera? Does it stir? Is its libretto interesting? Its music riveting? Its musicians equal to the task? More to the point, and to the point of those who seek to see it shuttered, are the “bad” characters, the Palestine Liberation Front hijackers, represented with any human sympathy? If so, I say “good.” Because isn’t the very point and soul of art to demonstrate the human endeavor in all its multifaceted messiness? Its mix of life-affirming and violent impulses? Jews of all people know this to be true. The Hebrew Bible itself is proof of some deep, unvilifiable truth that characters on a page can only truly live if they are depicted in all their human complexity.

Thus the Old Testament is filled with people who, at best, are hugely flawed—off the top of my head, King David (adultery was the least of his sins) springs to mind, as does Abraham himself, the first human to hue to the call of God (he passed his wife off as his sister while they were sojourning in Egypt, whereupon she was taken into Pharaoh’s household). At its best, art pierces the heart, shatters the ego, shakes us to our bones or lifts us out of our seats. At its middling, it entertains. At its worst, it fails—becoming trite, clichéd, hackneyed, uninspired and uninspiring. And beyond that, it isn’t art, or even failed art, at all: it’s propaganda. It’s brainwashing. It’s a sledgehammer wielded in the service of power.

I myself have a secret list of books and movies that I wish would just go away, and at the very top of the list is the anti-Jewish piece of blood-soaked trash that was Mel Gibson as Jesus Christ in the 2004 movie The Passion of the Christ, which, among other historical lies, showed Roman legionnaires as being on the side of loving kindness and Jewish Jerusalemites on the side of murder.

And I argued my head off about it too. But that’s what we get to do in America: argue. Which is why the storm of protest over the current rendition of “The Death of Klinghoffer” is both legal and even, in some ways, utterly American. But you really have to wonder why, in a society that celebrates millions of ways of self-abasement, hyper-sexualization of young people, the debasement of women in order to sell products and all manner of basic greed, in a country where your average citizen has access to more than 1,000 TV channels and endless Internet-based entertainment, where sleaze, violence, and pornography are accepted as part of the price we pay for democracy, we focus on high art as the locus of ill will.

Jennifer Moses is a writer and painter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com