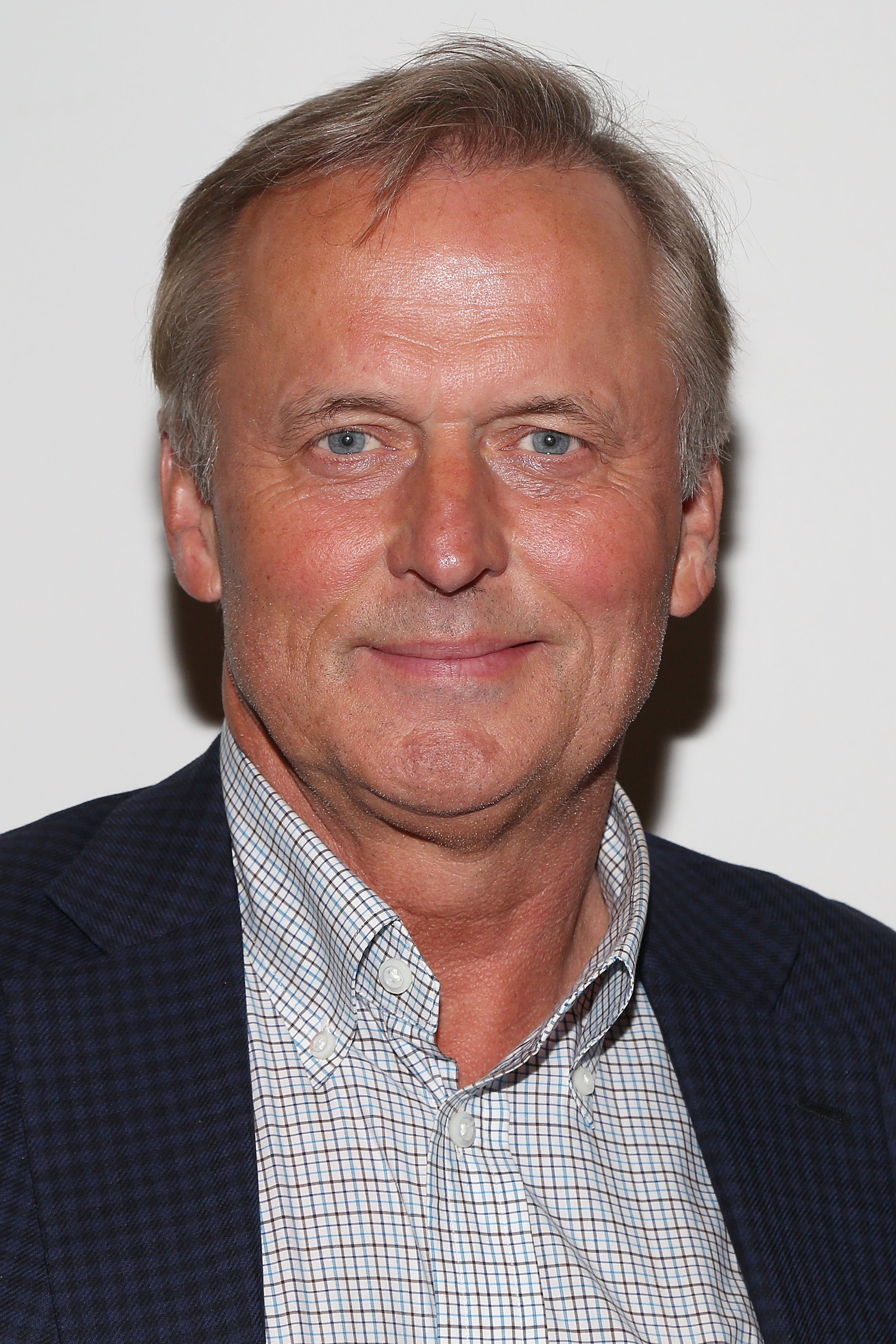

Last week John Grisham, the best-selling author of legal thrillers, triggered a storm of online criticism by arguing in an interview with the Telegraph that criminal penalties for possessing child pornography are unreasonably harsh. Grisham, who has since apologized, spoke rather loosely, overstating the extent to which honest mistakes account for child-porn convictions and the extent to which those convictions expand the prison population.

But he was right on two important points: People who download child pornography are not necessarily child molesters, and whatever harm they cause by looking at forbidden pictures does not justify the penalties they often receive.

Under federal law, receiving child pornography, which could mean downloading a single image, triggers a mandatory minimum sentence of five years—the same as the penalty for distributing it. Merely looking at a picture can qualify someone for the same charge, assuming he does so deliberately and is aware that web browsers automatically make copies of visited sites. In practice, since the Internet nowadays is almost always the source of child pornography, this means that viewing and possession can be treated the same as trafficking.

The maximum penalty for receiving or distributing child porn is 20 years, and federal sentencing guidelines recommend stiff enhancements based on very common factors, such as using a computer, possessing more than 600 images (with each video clip counted as 75 images) and exchanging photos for something of value, including other photos. In a 2009 analysis, federal public defender Troy Stabenow showed that a defendant with no prior criminal record and no history of abusing children would qualify for a sentence of 15 to 20 years based on a small collection of child pornography and one photo swap, while a 50-year-old man who encountered a 13-year-old girl online and lured her into a sexual relationship would get no more than four years.

Nine out of 10 federal child-porn prosecutions involve “nonproduction offenses”: downloading or passing along images of sexual abuse as opposed to perpetrating or recording it. As a result of congressional edicts, the average sentence in such cases rose from 54 months in 2004 to 95 months in 2010, according to a 2012 report from the U.S. Sentencing Commission (USSC). The penalties have become so severe, the commission noted, that judges frequently find ways to dodge them, resulting in wildly inconsistent sentences for people guilty of essentially the same conduct. In a 2010 survey, 71% of federal judges said mandatory minimums for receiving child pornography are too long.

State sentences can be even harsher. Dissenting from a 2006 decision in which the Arizona Supreme Court upheld a 200-year sentence for a former high school teacher caught with child pornography, Vice Chief Justice Rebecca Berch noted that the penalties for such offenses were more severe than the penalties for rape, second-degree murder and sexual assault of a child younger than 12.

These draconian sentences seem to be driven largely by the assumption that people who look at child pornography are all undiscovered or would-be child molesters. But that is not true.

The sentencing commission found, based on criminal records and additional information in presentencing reports, that 1 in 3 federal defendants convicted of nonproduction offenses in the previous decade had known histories of “criminal sexually dangerous behavior” (including prior child-pornography offenses). Tracking 610 defendants sentenced in fiscal years 1999 and 2000 for 8.5 years after they were released, the USSC found that 7% were arrested for a new sexual offense.

Even allowing for the fact that many cases of sexual abuse go unreported (as indicated by victim surveys), it seems clear that some consumers of child pornography never abuse children. “There does exist a distinct group of offenders who are Internet-only and do not present a significant risk for hands-on sex offending,” says Karl Hanson, a senior research officer at Public Safety Canada who has co-authored several recidivism studies.

Another argument for sending people who look at child pornography to prison, emphasized by the Supreme Court in its 1990 decision upholding criminal penalties for mere possession, is that consumers create a demand that encourages production. Yet any given consumer’s contribution to that demand is likely insignificant, and this argument carries much less weight now that people typically obtain child pornography online for free.

Defenders of harsh penalties for looking at child pornography also argue that viewing such images imposes extra suffering on victims of sexual abuse, who must live with the knowledge that strangers around the world can see evidence of the horrifying crimes committed against them. But again, any single defendant’s contribution to that suffering is apt to be very small.

Tellingly, people who possess “sexually obscene images of children,” such as “a drawing, cartoon, sculpture, or painting”—production of which need not entail abuse of any actual children—face the same heavy penalties under federal law as people caught with actual child pornography. That provision, like the reaction to Grisham’s comments, suggests these policies are driven by outrage and disgust rather than reason. There is clearly something wrong with a justice system in which people who look at images of child rape can be punished more severely than people who rape children.

Jacob Sullum is a senior editor at Reason magazine and a syndicated columnist.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com