For several years in the late 1930s and early 1940s, during the summer months, Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich held what came to be known as “A Day of German Art,” conceived as a kind of Aryan-inflected kickoff for the annual Great German Art Exhibition in Munich. Paintings, sculpture and spectacle combined to celebrate a strenuously Nazified vision of Teutonic culture—one in which German legends and myths were bent to the service (and the aesthetic) of the Reich.

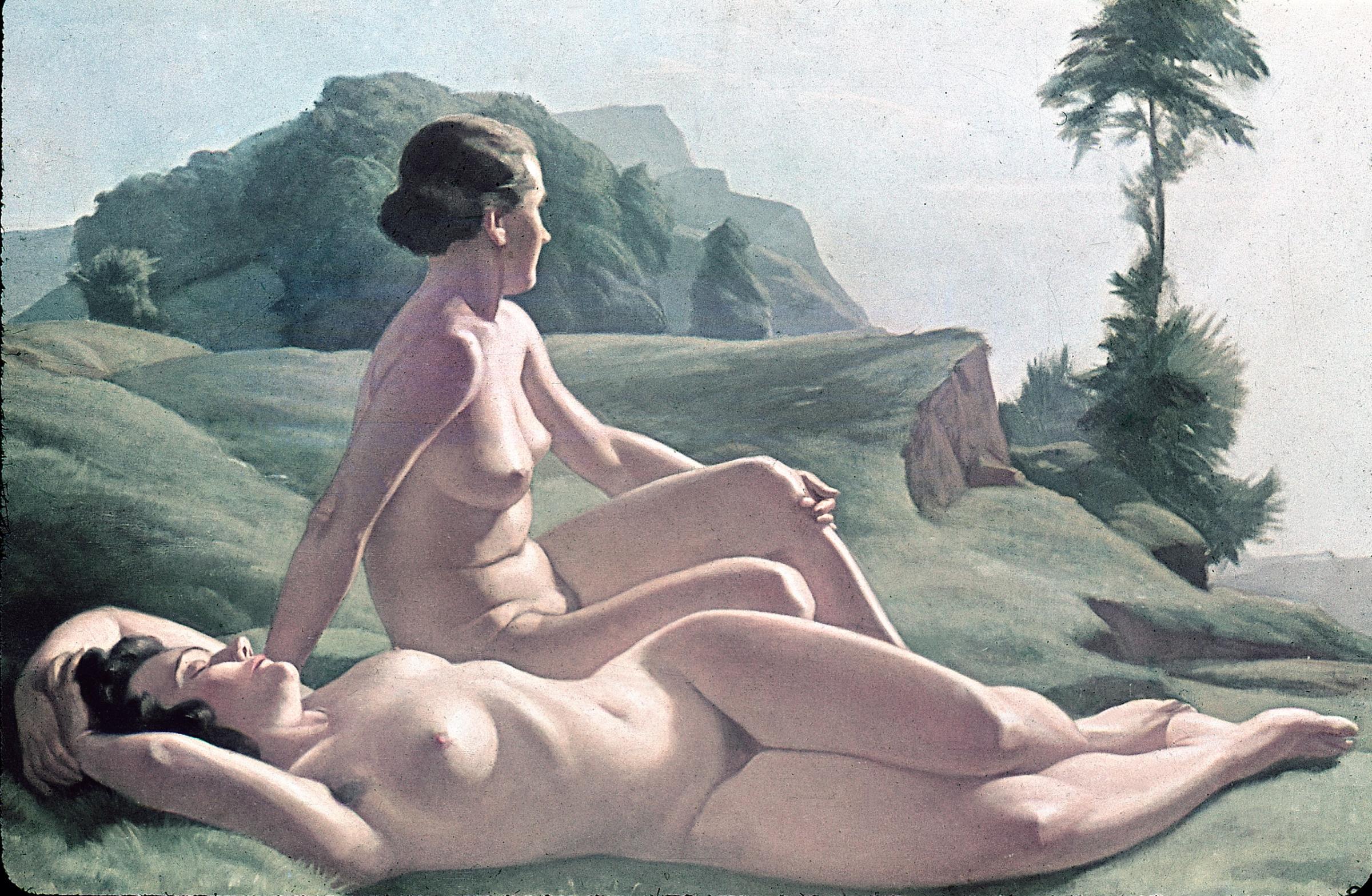

“Approved” German art, after all, was yet another form of Reich propaganda, utterly in line with radio broadcasts, photographs, films and other vehicles designed to spread the Nazi gospel. Hitler and others extolled realist paintings and sculptures, while dismissing as “degenerate” the art of Surrealists, Fauvists, Expressionists and other Moderns. The idyllic and the mythological, as well as scenes depicting and romanticizing family values, hard work, robust physicality, the military and, of course, the Fatherland’s leaders were, in the Reich’s eyes, the only true, legitimate subjects for art.

Here, in Hitler’s own words, from a speech he gave during the first “Day of German Art” in 1937, was the vision that the Führer and his followers—Goebbels, Bernard Rust, Alfred Rosenberg and others—formulated and shoved down the (often acquiescent) public’s throat during the run-up to World War II:

It was not Bolshevik art collectors or their literary henchmen who laid the foundation for a new art or even secured the continued existence of art in Germany. No, we were the ones who created this state and have since then provided vast sums for the encouragement of art. . . .

We are more interested in ability than in so-called intent. An artist who is counting on having his works displayed, in [the Haus der Kunst, or House of Art] or anywhere else in Germany, must possess ability. . . . [But] from the pictures submitted for exhibition, I must assume that the eye of some men shows them things different from the way they really are. There really are men who can see in the shapes of our people only decayed cretins; who feel that meadows are blue, the heavens green, clouds sulfur-yellow. They like to say that they experience these things in this way.

I do not want to argue about whether or not they really experience this. But in the name of the German people I only want to prevent these pitiable unfortunates, who clearly suffer from defective vision, from attempting with their chatter to force on their contemporaries the results of their faulty observations, and indeed from presenting them as “art”. . . .

I know, therefore, that when the Volk passes through these galleries it will recognize in me its own spokesman and counselor [ . . . ] it will draw a sigh of relief and joyously express its agreement with this purification of art. And this is decisive, for an art that cannot count on the ready inner agreement of the broad, healthy mass of the people, but which must instead rely on the support of small, partially indifferent cliques, is intolerable.

By the time the last “Day of German Art” took place in 1944, the “invincible” German army that had swept across Europe a few years before, seemingly conquering at will, was routinely being routed by Allied forces from the east and the west. By the late spring of 1945, Hitler, Goebbels, Rust and most of the rest of the Reich’s leadership was dead, or on the run.

The Haus der Kunst in Munich, meanwhile, still stands. No longer serving as a full-fledged museum, the enormous building now houses temporary and traveling exhibitions, often featuring the sort of “degenerate” art that the Nazis railed against, so loudly and so futilely, not so very long ago.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com