Concern over the corrupting influence of the media is nothing new.

On this day — Oct. 20 — in 1947, members of the House Un-American Activities Committee began an investigation into alleged communist influences in the film industry as the post-World War II “Red Scare” ramped up towards its peak. (Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, the namesake of an era marked by anti-communist paranoia, was not involved with the Congressional committee, although their aims overlapped.) Fearing a conspiracy that would inject propaganda into productions and recruit movie-going Americans to communist causes, the committee subpoenaed more than 40 actors, directors, writers and studio executives, whom they grilled about their political affiliations and asked to name names of other Hollywood communists.

And while 80 celebrities — including Lauren Bacall, Humphrey Bogart, Gene Kelly and John Huston — signed a petition denouncing the committee as un-American itself for probing the politics of individual citizens, the anti-communist momentum of the day carried the hearings forward.

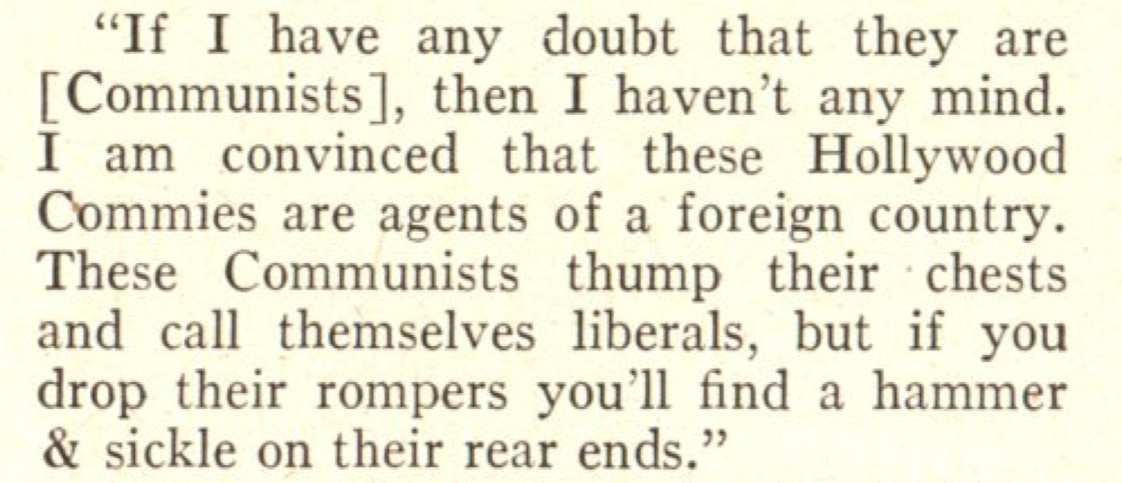

Some of those subpoenaed cooperated fully with the committee, confirming its fears that subversives were at work in Hollywood. These “friendly witnesses” included Ronald Reagan, who testified that a “small clique” of communists “have attempted to be a disruptive influence” within the Screen Actors Guild, and Walt Disney, who declared that they had been behind a strike at his studio. Disney felt particularly vulnerable to the Red Menace, according to his testimony, in which he alleged that one communist agitator, the union organizer Herbert Sorrell, swore “he would make a dust bowl out of my plant if he chose to.” Disney knew Sorrell was a communist, he said, because of “having seen his name appearing on a number of Commie front things,” which then went on to smear Disney’s name.

On the other hand, ten screenwriters and directors refused to testify, arguing that the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the freedom to belong to any political organization they chose. Congress didn’t see it that way, and a month later the men were cited for contempt and ultimately sentenced to a year in prison each.

In prison, one of the Hollywood Ten, as they came to be known, discovered warmer feelings for the committee. Director Edward Dmytryk testified a second time in 1951, outdoing even Reagan and Disney in his friendliness. As TIME reported in its coverage of the hearing:

This time Dmytryk not only admitted membership in the party in 1944-45; he also gave the committee a longer list of party members (26) than any other witness to date and the best summary yet of the Communists’ ‘Operation Hollywood.’

Those names joined a blacklist that destroyed hundreds of film careers. Dmytryk, however, speaking “with the surprised air of a man discovering sin for the first time,” said he believed the names should be known, and communism routed.

“This is treason and it means the party is committing treason,” he testified. “For this reason, I am willing to talk today.”

Read TIME’s 1951 coverage of Dmytryk’s change of heart, here in the archives: Operation Hollywood

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com