Updated Saturday, Oct. 11

Since early evening on Friday, many in India were furiously searching the web for the name “Kailash Satyarthi” as it started trending on social media. This was right after the Nobel Prize committee in Sweden announced that Satyarthi, from India, was one of this year’s (and India’s second) Nobel Peace Prize winners.

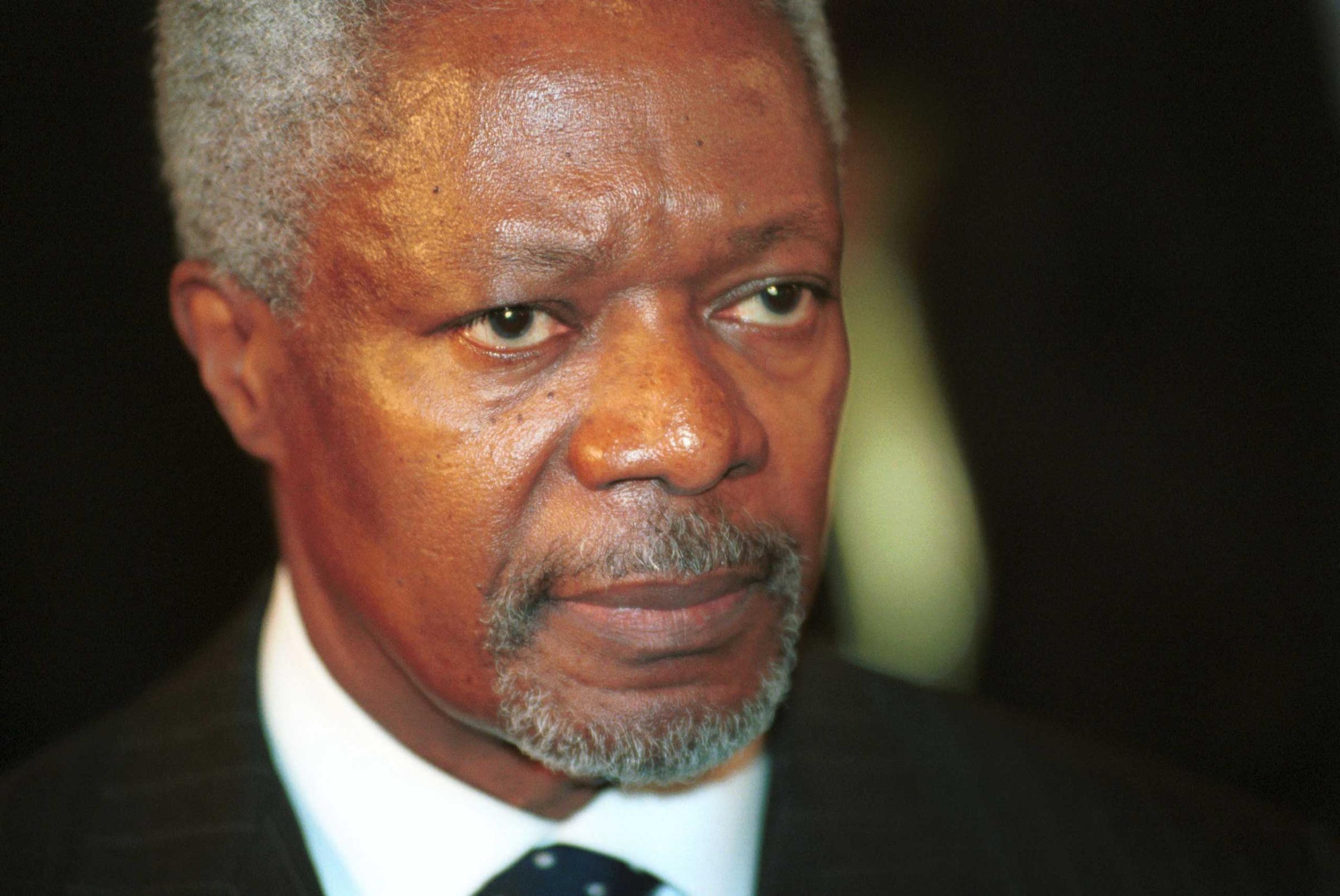

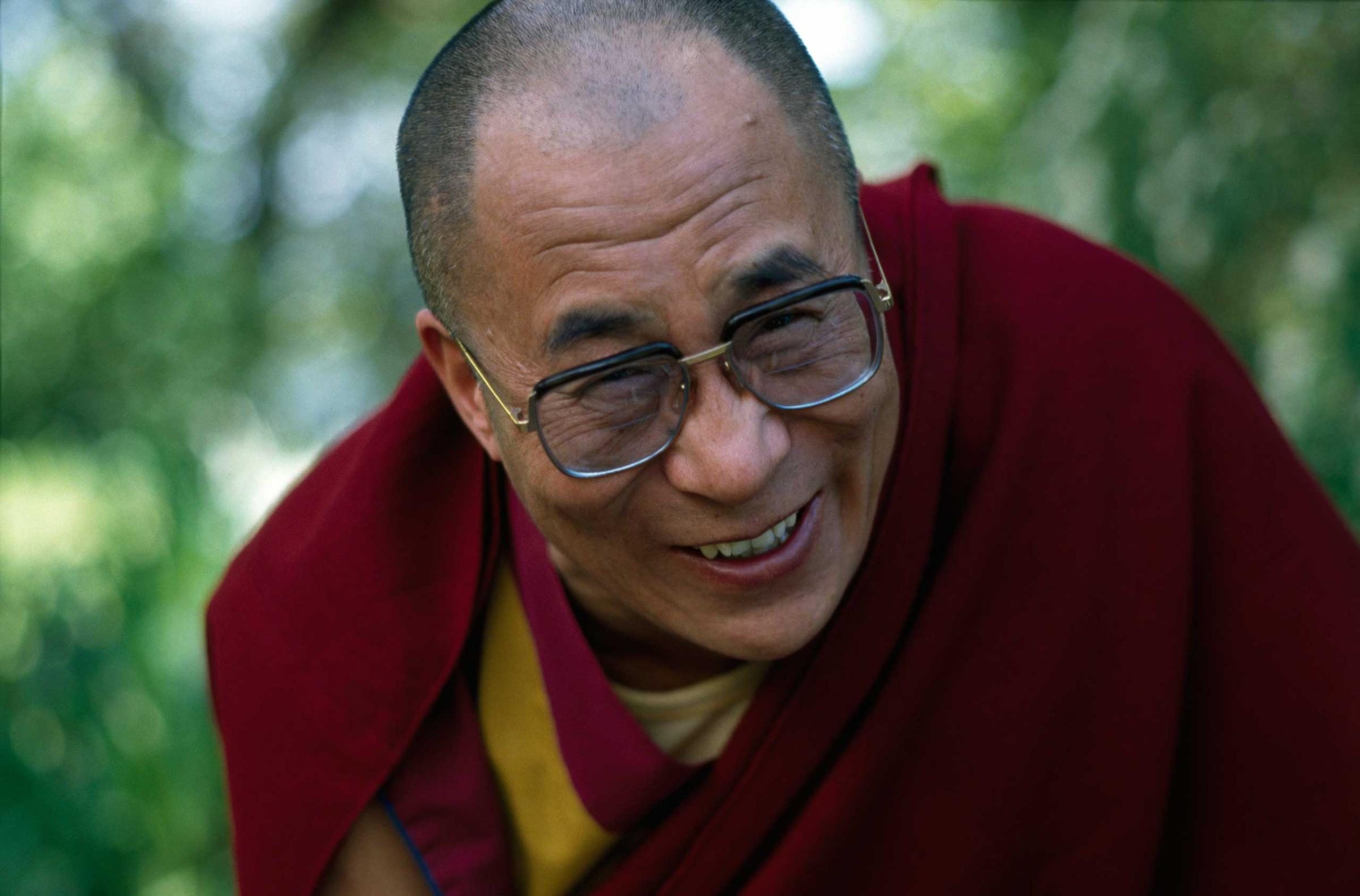

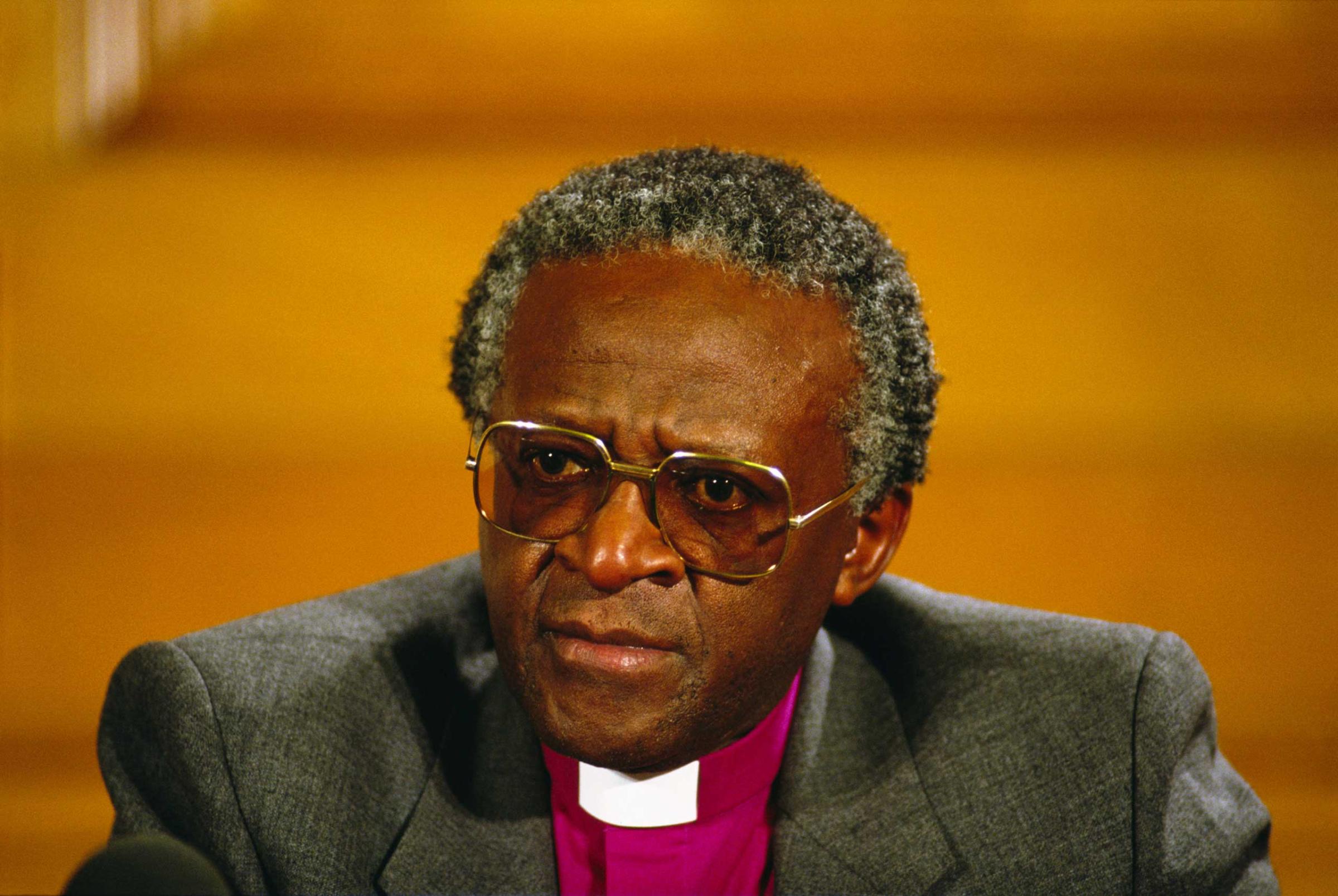

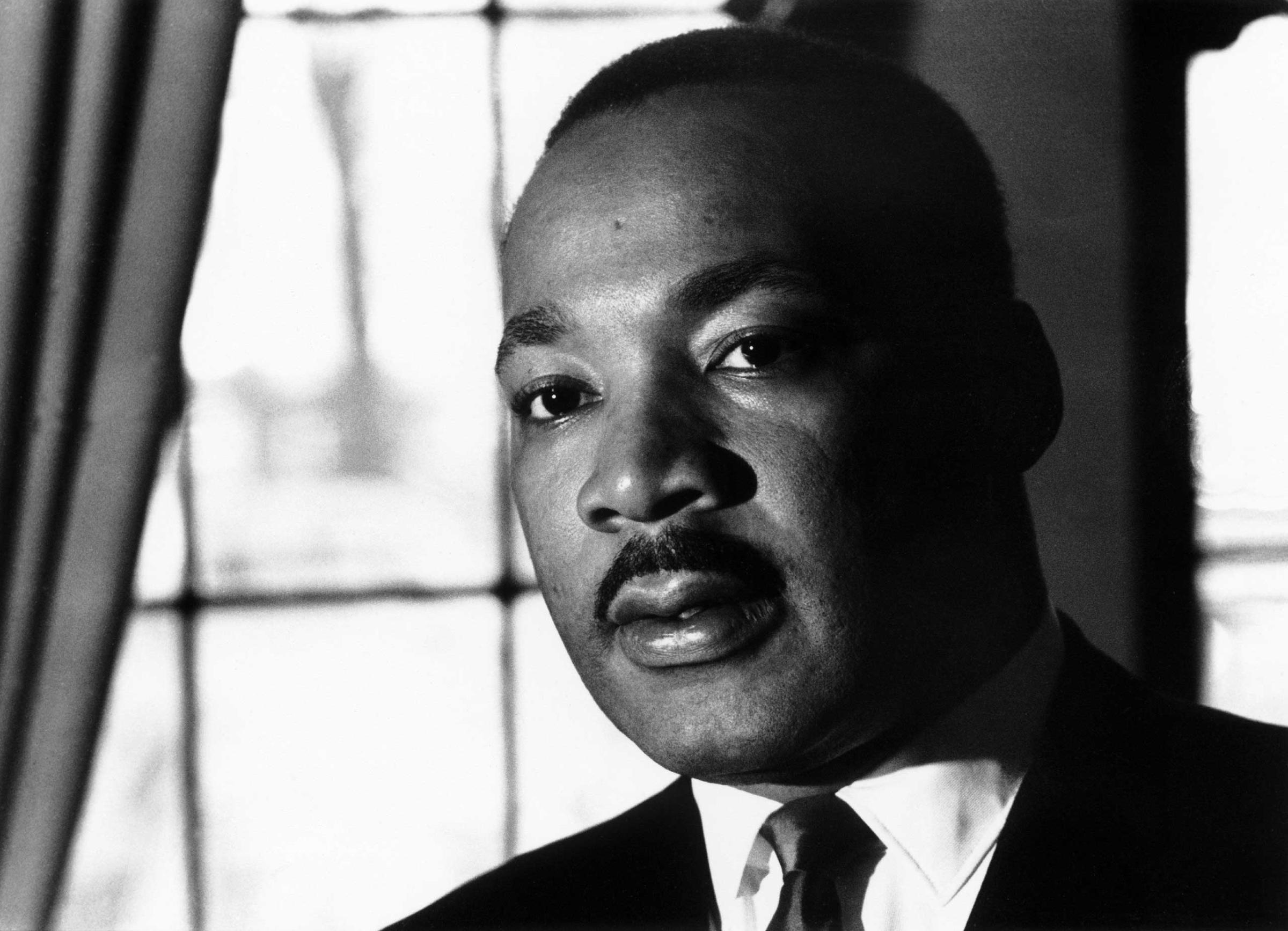

The highly coveted Nobel Peace Prize goes out every year to trailblazers in world peace and activism. U.S. President Barack Obama, Mother Teresa, the Tibetan spiritual leader Dalai Lama, Burmese political activist Aung San Suu Kyi and anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela are just some of the world’s foremost leaders who have won the award.

See the 20 Most Famous Nobel Peace Prize Laureates

But Satyarthi is nowhere as well known as any of them. In fact, he’s even lesser known than his young co-recipient Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani teen activist shot in the head by the Taliban while going to school in 2012 and has since been fighting for children’s right to education in her home country and abroad.

But the 60-year-old New Delhi-based activist, originally from the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, has been almost singlehandedly leading India’s fight against child slavery for over three decades. To that end, he founded a grassroots nonprofit, Bachpan Bachao Andolan, or Save Childhood Movement, in 1980, which has to date rescued more than 80,000 Indian children from various forms of exploitation, like child labor and child trafficking.

India has one of the largest working child populations in the world. There are close to 50 million child laborers in the country, more than 10 million of them in bonded labor, having been sold by their families to work off loans they couldn’t repay.

But despite the remarkable success of his organization, Satyarthi, who is trained as an electrical engineer, has preferred working almost anonymously in the backdrop. His work has involved organizing almost weekly raids on Indian manufacturing plants and other workplaces that employ children often forced into bonded labor. Since 2001, Satyarthi’s organization has convinced families in more than 300 Indian villages across 11 states to avoid sending their children to work, and instead put them in school and send them to various youth programs.

“He never wanted his name to come before the work of the organization,” R.S. Chaurasia, chairperson of the movement and Satyarthi’s long time associate, told TIME. “Very few people have the kind of conviction he possesses.”

Satyarthi’s biggest achievement, however, has been to grab and retain the world’s glare on the problem. He organized the Global March Against Child Labor in the 1990s to raise awareness and free millions of children shackled in various forms of modern slavery.

“To employ children is illegal and unethical,” Satyarthi has written on the Global March Against Child Labor website. “If not now, then when? If not you, then who? If we are able to answer these fundamental questions, then perhaps we can wipe away the blot of human slavery.”

He also founded the widely recognized international tag “RugMark” that guarantees carpets being sold were made in factories free of child labor. India is the largest exporter of handmade carpets and a large number of the weavers are underage child workers. Satyarthi hopes his prize will renew focus on the plight of these children.

“It’s the biggest ever recognition for the struggle of these children and the issue of child labor worldwide,” Satyarthi had told TIME over the phone on Saturday morning. “The amount of conversations it has created around the issue in the last six to seven hours has not been seen in the last 600 years!”

In one of his initial reactions to the award, Satyarthi told an Indian news channel that he hopes the recognition will once again bring and keep the spotlight on the exploitation of children globally. In India, for sure, the often-fringe topic of child labor has gained some mainstream clout—and Satyarthi’s Nobel prize will only bring more.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com