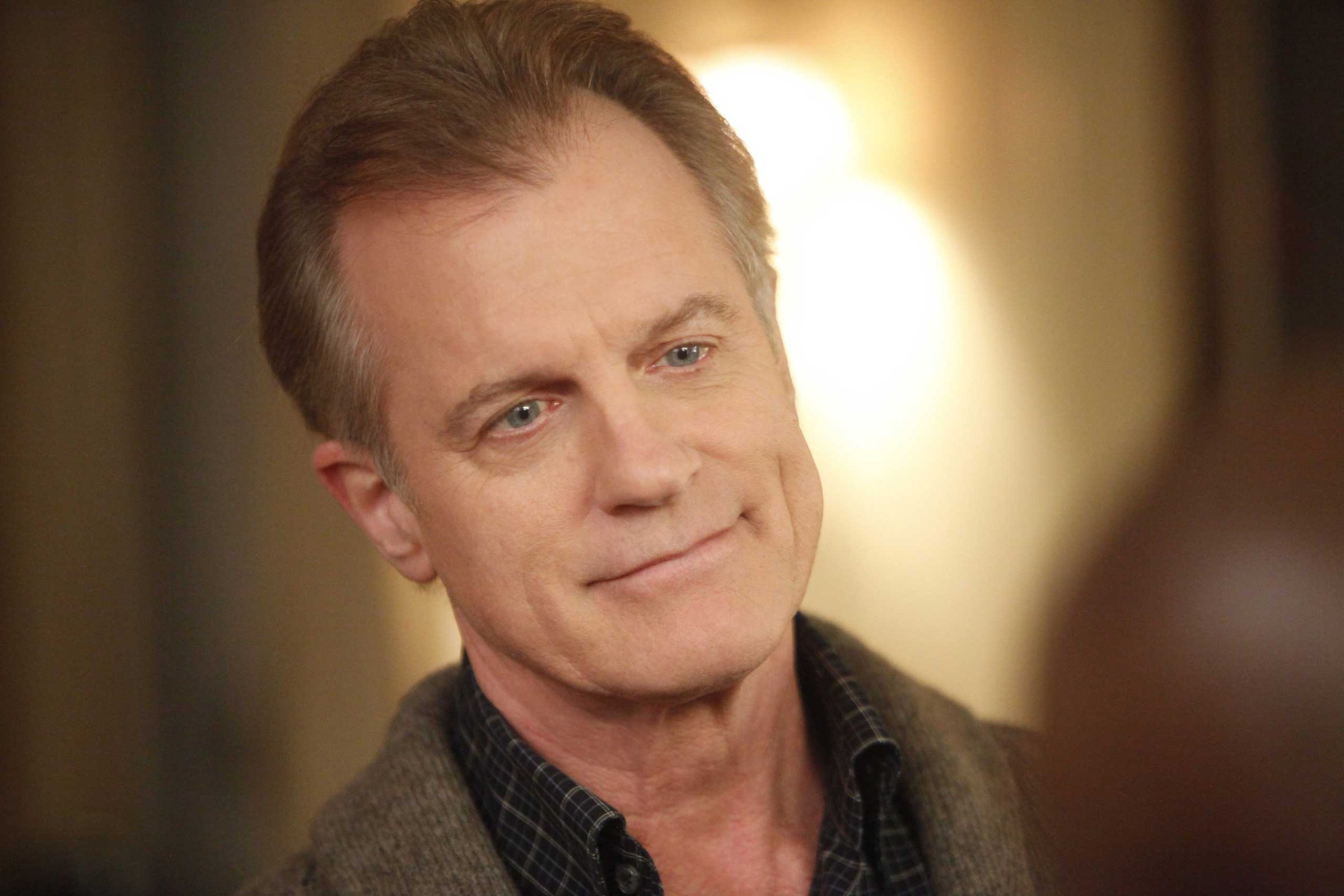

I don’t know Stephen Collins. Or his wife. Or their therapist.

All three are embroiled in a child sexual abuse investigation that has likely taken on added significance given the release of an audiotape in which Mr. Collins appears to admit to illegal sexual behavior against three girls. The revelation was shocking, and it leads to a familiar set of questions.

To me, one stands out: How could this have been prevented?

As a public, we’re always shocked to learn that an apparently upstanding citizen has molested children. The news flies in the face of our collective perception that sex offenders are monsters. But there are two problems with this perception.

It blinds us to warning signs when a potential offender is someone we know, love or respect—someone who is patently not a monster: The teenage boy who prefers the company of little kids to peers. The step-father who insists on putting the girls to bed by himself. The pediatrician who asks parents to “wait outside.”

And the idea that all sex offenders are monsters, and monsters are unpredictable, draws resources and political attention away from effective prevention efforts. We spend far more to address sex crimes after they happen.

In a case in which I served as an expert witness, “Tommy,” age 12, was convicted of sexually abusing his younger cousin. He spent five years in a juvenile prison—about $50,000 per year, to the cost of taxpayers—and another five years in a sex offender civil commitment program—another $63,000 a year. Never mind the court costs. By the time Tommy was released, his home state had “invested” over half a million dollars in him. By comparison, the priciest violence prevention programs rarely cost more than $10,000 per family.

Yet we don’t have prevention programs that target adolescents at risk of sexually abusing children, even though they account for more than 50% of cases. All the emphasis is on after-the-fact policies. We must treat victims. We must detect and stop offenders. But if we really want to reduce harm, we need a stronger culture of avoiding the problem to begin with.

In my 25 years of research on sex-offender assessment, treatment and policy, I’ve met hundreds of offenders and reviewed the records of thousands of boys and men charged with sex crimes. But until last year, I’d never spoken with a non-offending pedophile. And until I did, I really did not recognize their existence. They were largely invisible, because the stigma and risk of coming forward to ask for help was simply too great.

Everyone loses when we ignore this group of non-offenders. I’ve spoken to young men who were horrified to realize they were attracted to younger children in adolescence, and that they were not growing out of their attraction. They described appalling childhoods, living in self-imposed isolation for fear of being discovered and labeled a pedophile. Several expressed self-loathing. Many considered suicide. As adolescents, they wanted help controlling their sexual impulses, but had nowhere to turn for help.

In Germany, where therapy is confidential (and where recording conversations without peoples’ knowledge or consent is illegal), thousands have reached out to the Prevention Project Dunkelfeld, which specifically targets men and adolescent boys—both ones who have acted on their impulses and ones who haven’t—attracted to children.

In the U.S., the stigma of pedophilia and the fear of criminal consequences is so great that non-offending pedophiles rarely seek help. Those who do may be turned away by professionals who are untrained or unwilling to help. These adults and adolescents are left to struggle on their own. Many – too many – do not succeed.

The best prevention programs focus on the individuals at highest risk of offending. But to get those individuals into an intervention, we must destigmatize the act of asking for help. The problem behavior must remain stigmatized, of course. But the act of asking for help should be met with encouragement and effective professional interventions.

When we hear about the next supposedly upstanding citizen offending against children, we’ll still ask how it happened. But it’s so much more effective to ask how we could have stopped it from happening in the first place. We will have that answer only when we insist on reasonable resources to develop a culture of prevention.

Elizabeth J. Letourneau is Director of the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse and Associate Professor, Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com