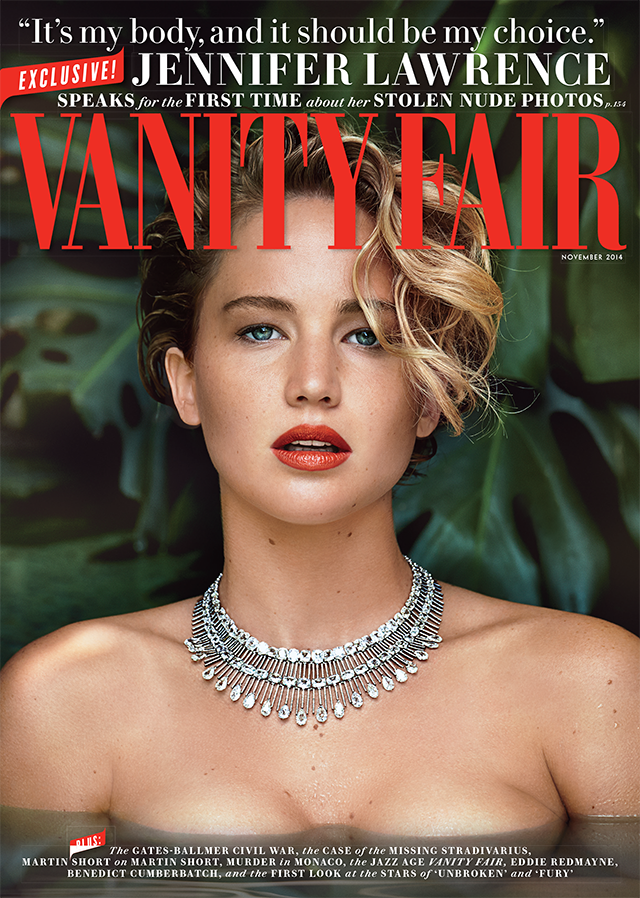

In a controversial, much-criticized post Wednesday on LinkedIn Pulse, business writer Bruce Kasanoff derided Jennifer Lawrence for daring to do the unthinkable (to him): bare her breasts in Vanity Fair magazine. Originally titled “Why Jennifer Lawrence’s Breasts Confuse Me” and later changed to “Why Jennifer Lawrence Confuses Me,” Kasanoff’s piece was riddled with ill-considered and outmoded ways of thinking about bodies, nudity and ownership of our stories. Kasanoff deleted the inflammatory article Thursday, telling Time.com via email, “My intention is to help people, not upset them.”

“If someone outraged me by publishing naked photos of my body, I’m pretty certain my next move would NOT be to then pose semi-naked for a national magazine, especially with a cockatoo,” Kasanoff wrote. As a man, Kasanoff will never know what it’s like to be a woman whose nude photos were stolen and leaked for the entire world to see, nor the ways that violation affects her. Yes, male celebrities such as Nick Hogan, son of Hulk Hogan, have also had their nude photos leaked, which is problematic, but they are less likely to come under the kind of scrutiny Lawrence has. In Hogan’s case, for instance, most of the commentary has focused back on women, namely photos of his mother, which the New York Daily News deemed “worse” than his own nude images, and of photos he’d possibly taken of underage girls. Male nudity simply doesn’t cause the same moral panic that female nudity does.

From a young age, girls are taught that our bodies, by the very nature of existing, are and should be on display, primarily for men’s pleasure. We all navigate that landscape differently, but there’s no single right approach to take. Frankly, we’re damned if we do indulge in the male gaze and damned if we don’t. But what’s missing from that worldview is that there are other gazes–namely, our own. By choosing to gaze back, to be unashamed and proud, we can take back a little of that power that’s so often used to belittle and make women feel that we are only sexual objects. By making that proactive decision to strip down for a camera, we are the ones saying first that we’re sexual subjects.

Posing nude, or topless, can be part of our self-expression. Of course, it doesn’t have to be, which is exactly the point: I doubt a celebrity as powerful as Lawrence was in any way coerced into baring her breasts, which means she got to make the decision about who would see those photos (Vanity Fair readers). She didn’t with the nude photos taken in private. That point is made repeatedly clear by her statements about the leak, saying it was “against my will” and made her “feel like a piece of meat that’s being passed around for a profit.

Kasanoff’s piece tries to play both sides of the fence, such as when people claim it’s okay to wear anything we want, but we shouldn’t wear something too enticing lest we be assaulted.

On Twitter, journalist Felix Salmon made a similar point, contrasting Lawrence’s statement to Vanity Fair–“I don’t want to get mad, but at the same time I’m thinking, I didn’t tell you that you could look at my naked body”–with an image of her topless, entirely ignoring the context she so clearly provided. At the risk of being redundant, having private, personal nude photos stolen and published is the complete opposite of consenting and posing for nude photos intended to be published in a widely read national magazine. There’s nothing similar about them except the nudity. By choosing to pose nude with her head held high, literally and figuratively, she’s making it clear that it wasn’t her body being ogled she objected to per se, but instead the illegal, nonconsensual manner in which the stolen photos were obtained. Lawrence is being chastised for daring to say that she is okay with nudity when it’s on her terms, as if once her photos have been released without consent, she should lose that privilege forever. The implications of that idea are extremely disturbing. As Brooke Burchill writes, also at LinkedIn Pulse, “The discussion here isn’t whether or not she wants to be seen as sexual, it’s whether or not she is in control of her own sexuality and how it is portrayed by the media and consumed by the public.”

I’ve posed for nude photos, both for lovers and for publication. Does that mean that anyone anywhere has the right to use the private photos for any purpose they like? Of course not. Yet Kasanoff and numerous commenters seem to think that once any woman bares her body, whether in private or public, they are immediately branded with the modern equivalent of a scarlet letter and forfeit all right to control anything that happens with their images. Witness Vanity Fair commenter SJWarrio, who wrote, “if she didn’t want the photos online she could simply not have them taken, it’s not like it was a paparazzi case, on the leaked photos, she KNOWS that somebody is taking them, her naked, looking at the lens.” The crime, it would appear, is in taking off her clothes, in brazenly, openly owning her sexuality.

Kasanoff paid lip service to his declaration that “Lawrence has the right to do anything she wants,” but then undermined that right by saying she is sending “confusing signals” by posing topless. No, she’s not. She’s saying, “Don’t steal photos of me (or anyone else), and don’t look at stolen photos because they are available because a crime was committed.” She’s also saying the complementary but not contradictory, “Feel free to look at these photos I opted to pose for of my own free will.” The only way to see these two viewpoints as “confusing” is to be confused about the nature of consent. Lawrence herself makes this very clear in the article, saying, “I started to write an apology, but I don’t have anything to say I’m sorry for.” Exactly. Yet scolds seem to think she owes them an apology for having the audacity to publicly claim her right to both pose topless for a magazine and have her privacy respected and not illegally invaded.

Whatever Jennifer Lawrence decides to do with her breasts and the rest of her body, they still belong to her–even if she’s letting us look at them.

Rachel Kramer Bussel is a New Jersey-based writer on sex, dating, books and pop culture. She teaches erotic writing workshops, pens the Let’s Get It On column for Philadelphia City Paper and is the editor of over 50 erotica anthologies such as Hungry for More and The Big Book of Submission.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com