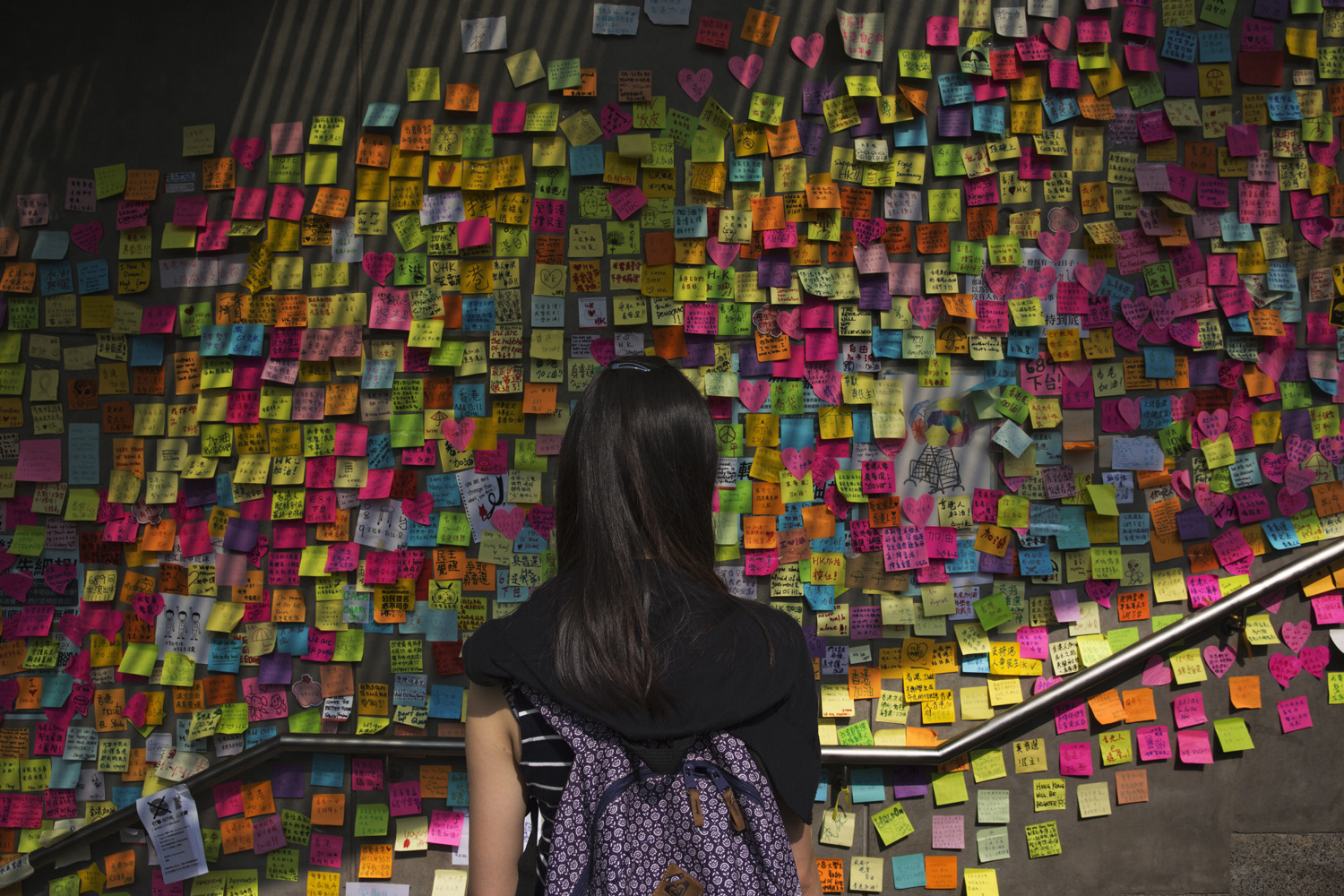

They have been pepper-sprayed and tear-gassed by police, pushed and punched by their opponents, drenched by torrential rain. Still, they stay. Since Sept. 22, in a historic act of civil disobedience, pro-democracy demonstrators–the overwhelming majority of them students–have occupied key financial and retail districts in one of the world’s great cities: Hong Kong. When their camps were attacked by thugs who the protesters say were backed by the state, more than 100,000 people rallied for peace. When the authorities set an Oct. 6 deadline for them to clear out, they held fast. Says 17-year-old Jennifer Wong, who is in high school: “I choose to stand up.”

The protesters are standing up for a say in government, starting with the election of Hong Kong’s chief executive (CE). Until now, the CE has been chosen by a 1,200-member electoral college made up largely of Hong Kong’s political and business elite. In 2017 the public will be allowed to vote for the CE, but the leadership in China, which has sovereignty over Hong Kong, has imposed conditions. Candidates must be vetted for “patriotism,” and only two or three can run. Officials say the new system represents progress; critics say it’s rigged to stifle dissent.

Young people are particularly concerned. Hong Kong is a rich city, but its wealth is concentrated in ever fewer hands. Big Business, particularly the city’s real estate sector, has inordinate influence over government policy. High property prices prevent many people from owning homes. Wages are stagnant. “We don’t see good prospects for our future,” says Katie Lo, 21, a university student.

That future would be brighter with democracy, Hong Kong’s youth believe, because it–at least in theory–would make the government more responsive to public needs. “People say to me, ‘If you want to change the world, go to university, then work as a government administrator or a businessman,'” says Joshua Wong, a protest leader who turns 18 this month. “No, to affect the world, you go to the streets.”

Many citizens are tired of the disruptions to their lives and want to reclaim those streets–a growing sentiment that officials may exploit to pressure the students in coming talks. Protesters are getting weary too. On the night of Oct. 7, only about 2,000 were at the main rally point, compared with the tens of thousands before. Still, Hong Kong has undergone a political awakening. Says Emily Lau, 62, a legislator and the head of Hong Kong’s Democratic Party: “Once people have been shown their power, they know how to use it again.”

–BY EMILY RAUHALA/HONG KONG. WITH REPORTING BY ELIZABETH BARBER, HANNAH BEECH AND NASH JENKINS/HONG KONG

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Emily Rauhala/ Hong Kong at emily_rauhala@timeasia.com