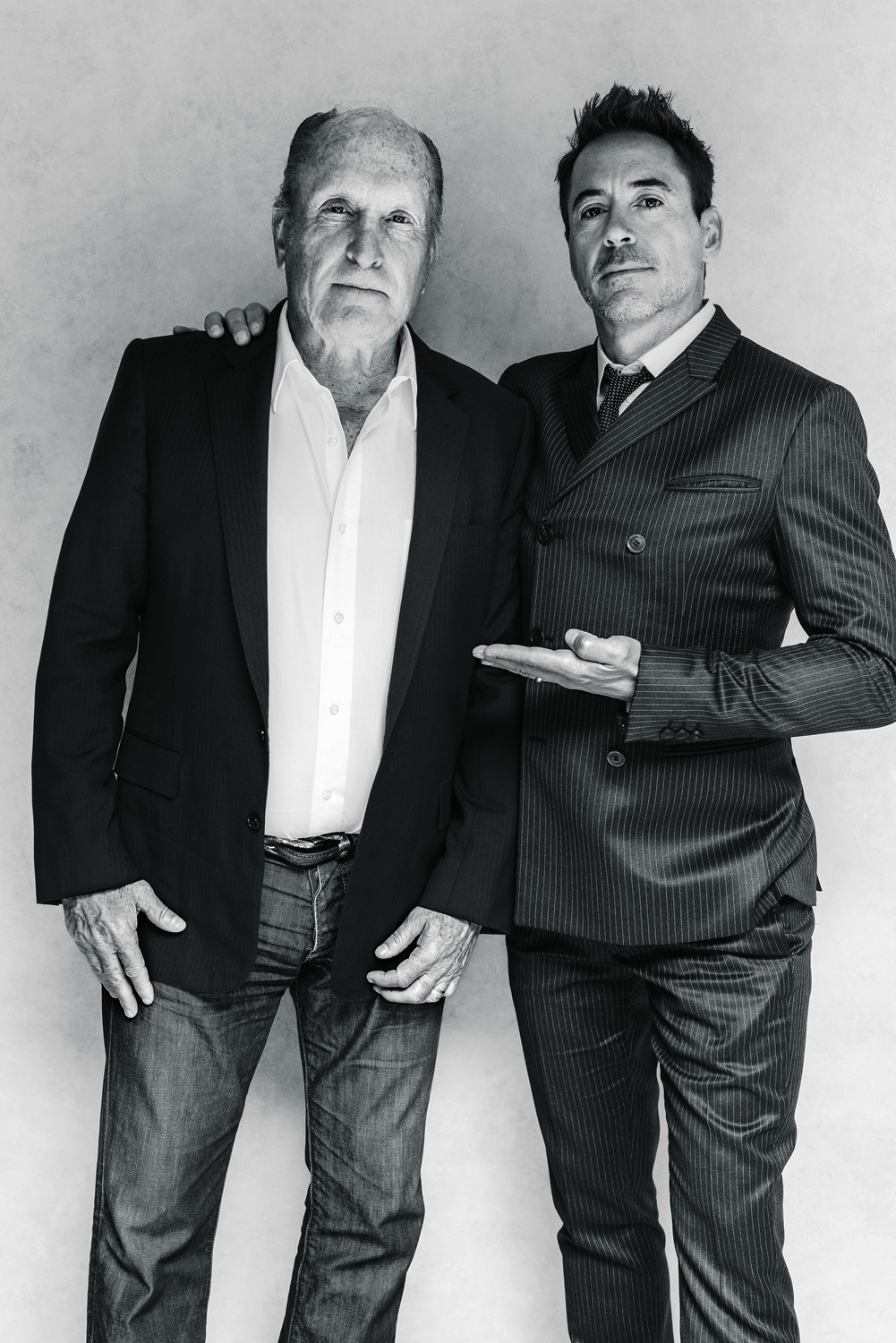

“How did I come to asking for a selfie in a swag hat?” Robert Downey Jr. asks, fidgeting with a fishing hat while looking over Venice’s Abbot Kinney Boulevard from the third-floor balcony of his gorgeous, three-story California production office. His chef is cooking a three-course meal for him and Robert Duvall, his co-star in The Judge, in which they play an estranged father and son, before they go out to screen the new movie for British Academy of Film and Television Arts voters. When Duvall walks in, there’s hugging, some chatting–about steak restaurants, football or horses, since that’s all Duvall likes to talk about–and then Downey’s request: “I want to ask you if we can take a picture with The Judge hats.” The two put on the promotional fishing hats while a Downey employee takes a cell-phone shot for social media.

Duvall, 83, didn’t want to be in the film at first, turning it down largely because of a scene in which Downey, 49, cleans him up after an accident on the toilet. “It was so negative. I said, ‘I don’t know if I want to do that, sh-tting all over yourself,'” Duvall says.

“Let me qualify that,” Downey says. “Sometimes you’re considering something, and you say, ‘Is this really worth it?'”

“And I’m tired of dying in movies,” Duvall adds. “I’m f-cking dying all the time. Every time you turn around, some guy is getting old and gets cancer. I don’t want to do that sh-t. But this is well written and accompanied by certain talents, so you say, ‘I have to look at this.'”

Whereas Downey is unerringly charming–instantly ferreting out commonalities and revealing minor intimacies while energetically giving an office tour in sweats and a T-shirt from his martial-arts school–Duvall, in stiff jeans and a blue blazer with gold buttons, is unerringly honest. Which is the basis for the conflict in The Judge, the first movie produced by Team Downey, the company formed by the actor and his wife Susan. Downey plays a slick, churlish Chicago lawyer who defends creeps (“Everyone wants Atticus Finch until there’s a dead hooker in a hot tub”) and returns to his small hometown, where he defends his strict, estranged father, the local judge, in a murder trial. It’s a simple dynamic, which director David Dobkin pitched to the two actors as a western with “a sheriff dad and his gunslinger son.” It comes from Dobkin’s own story–a boomer classic retold by Gen X–of having to pause his messy midlife to take care of a sick parent he had issues with.

The movie also has Vera Farmiga, Billy Bob Thornton, Vincent D’Onofrio and Dax Shepard, but they don’t get much screen time. “The first audiences thought the movie was really slow and wanted to get to Downey and Duvall,” Dobkin explains. “So we went the other way in the editing studio. Almost everything with Downey and Duvall is in the movie. There’s one scene that we cut out. And it’s amazing.”

After Downey’s chef brings out crab cakes made from Duvall’s mom’s recipe (which was from Reader’s Digest), Downey goes over the long list of Duvall roles he loves and how this one is different, an internalized Great Santini–the 1979 film that brought Duvall his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Leading Role, before he won for 1983’s Tender Mercies. When I ask Duvall when he first noticed Downey, the world’s highest-paid actor, he pauses, taking a sip from his root beer. Downey, again, intervenes to help his co-star. “I think in Toronto,” he jokes, referring to the Toronto International Film Festival, where the film premiered. “I think in the screening.” Eventually, Duvall says it was Sherlock Holmes, which came out five years ago. “Sometimes I go to the movies. Sometimes I don’t,” Duvall explains. “They asked what my favorite performance of his is, and I said Chaplin, and I haven’t seen it yet.” A little later, talking about how universal father-and-son stories are, Downey has to pause to tell Duvall what Less Than Zero was.

As Downey pulls out bottle after bottle of vitamins and amino acids to take with his meal, Duvall says he doesn’t take nearly as many pills. “He’s a very healthy guy. Tremendously healthy guy,” Duvall says of Downey.

“You didn’t know me when, did you?” Downey replies, an arch reference to his well-documented issues with addiction.

“I told you on that other movie, I saw you sitting in the corner. You looked very lonely and alone,” says Duvall of working together on Robert Altman’s 1998 film, The Gingerbread Man, though they never spoke on the set.

“Why didn’t you come over and give me some condolences?” Downey asks.

“I was in and out. We were all in and out,” Duvall says. “One day I was rehearsing in [Altman’s] house and there was no food, so by mistake I ate their kid’s lunch. Why didn’t he give me something to eat?”

“If you eat my kid’s lunch, it would be an honor. It would give him a story,” says Downey. Replies Duvall: “I never even saw the movie.”

Not Trying to Be Seen

Downey kept the set of the judge loose, taking moments between shooting heavy scenes to get the other actors to compete at improv, to see who could do the best zombies after they had all seen World War Z. But Duvall keeps a set even looser. He was the one asking everyone to go out for dinner, when he wasn’t bringing in Texas-marshal buddies to visit the set (he wrote and directed Wild Horses, an upcoming movie about marshals, with James Franco and Josh Hartnett) or taking off to meet Tom Brady. “The most surprising thing was how open he was to all the improvisations and how willing he was to play before the cameras started going,” says D’Onofrio, who plays Duvall’s other son. “I held him too high and didn’t realize he would do that kind of thing.”

“The mystique that people hold around someone like Duvall, he’ll break that down as soon as you meet him,” Downey says. “He’s not interested in utilizing that. I wonder why that is?” Duvall deflects it by talking about Marlon Brando, eventually saying that in The Godfather, he would have liked to see him tip over a table to show his violence.

But over fish, creamed spinach and steak with truffled mushrooms, Duvall says he likes acting now more than in the 1970s. Downey adds, “If you talk to iconic figures of their generation and you talk about actors these days, they’ve got plenty to say about how it used to be and what these kids don’t know.” Duvall nods. “I’m the opposite,” he says. “They’re better now. I worked with a director who said, ‘When I say action, tense up, goddamn it.'” He’s harking back to the way Henry Hathaway directed him in True Grit–the 1969 version starring John Wayne. “There’s less of that now. The good directors want to see what you can do. If you did Moneyball 40 years ago, it would have been inundated with caricature performances.”

Neither Downey nor Duvall writes down notes about his characters, and director Dobkin doesn’t rehearse material, wanting to capture the first interactions onscreen. And Duvall would always prefer to hold back. Downey remembers, “Bobby would say, ‘Wait, wait, wait–let’s not get to the arguing here. Remember, that crescendos in the kitchen.'” Duvall’s approach, says Downey, was “Let’s not repeat a feeling.” He moves his arms in a figure eight. “I see Bobby do this a lot with his hands,” he says. “Nothing is being jammed down your throat.”

When Dobkin looked at the dailies, he was surprised by how subtle Duvall was. “We’d look at his closeups and be like, ‘How is he doing that?'” the director says. “There’s so much going on inside of him and so little outside. His choices are so simple. He’s just existing in the space. He’s transcended acting.” To Dobkin’s relief, Downey kept it nearly as simple. “An actor like Downey goes from being a big movie star to a [smaller-scale] dramatic movie, and a lot of them chew the scenery up to prove something. And he never does that. He’s not trying to be seen, ever.”

After the chef serves slices of gluten-free, dairy-free banana cream pie (it keeps Downey feeling light), Downey drinks a mugful of espresso (it keeps him awake). Duvall asks if he can keep the swag fishing cap from the photo. “I need a hat,” he says. Downey responds, “Trust me, we’ve got plenty,” and leads Duvall downstairs to an office to load him up with promotional hats, shirts and paperweights. It doesn’t really feel all that different from a scene in The Judge.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com