Emerging and infectious diseases are having a moment for all the worst reasons, with credit due to the Ebola outbreak. But scientists studying other emerging diseases beyond Ebola are hopeful that the attention on the disease—and what can happen without available therapeutics—is here to stay.

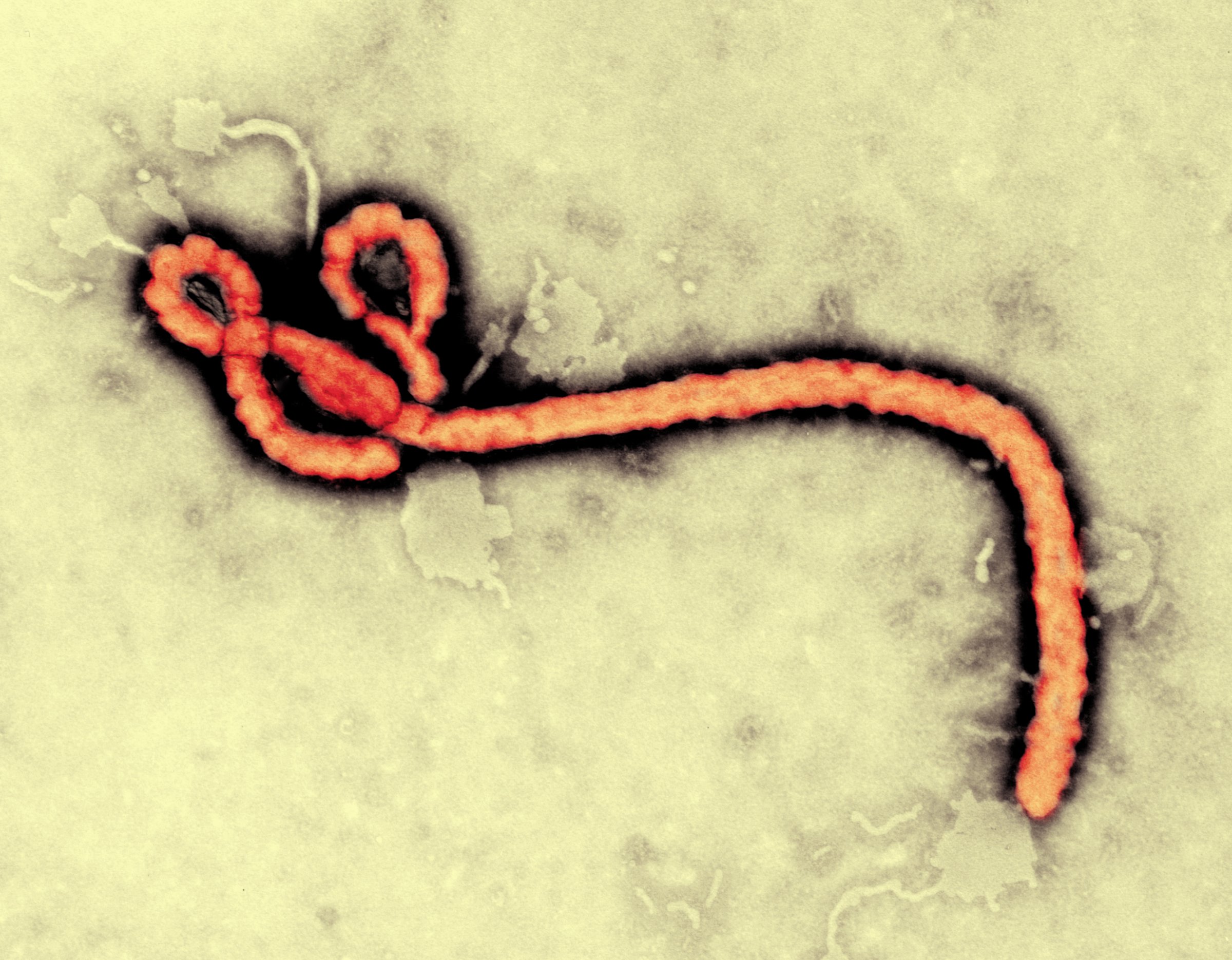

The fact that there are no drugs or vaccines approved for Ebola isn’t for a dearth of research, but rather because there’s scant financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to take on the treatments. “We’ve been studying Ebola for almost a decade and we’ve always been interested in Ebola. It’s like the rockstar of viruses,” says Michael Katze, a professor of microbiology at the University of Washington. His team studies the responses of hosts (like animals) to viruses from Ebola to SARS to hepatitis C. “All the major players in Ebola have had vaccines tested in non-human primates”—and they work, he says.

But we lack vaccines or cures for many other emerging and infectious diseases, including bird flu and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Two people brought the disease to the United States in May 2014.

Viruses, though lumped together as infectious agents, are very different. A bird flu virus is quite different from an Ebola virus in a variety of ways, from how they attack their hosts to how they are transmitted to how virulent they are. The science behind the viruses isn’t uniformly advanced, either. But the outbreak of widespread infection from diseases like Ebola, bird flu, SARS and MERS can look quite alike.

Dr. Robert Belshe is a professor of infectious diseases, allergy and immunology at Saint Louis University and published a study in JAMA on Oct. 7 on his most up-to-date work on bird flu. “Ebola is a very different virus [from bird flu], but if you take a step back and ask ‘what are the public health consequences of these two viruses,’ they are sort of similar,” says Belshe. “If bird flu develops the ability to transfer person to person, it would be a disaster much greater than the Ebola disaster happening right now. It’s a very different virus, but has similar lessons for us. We need tools to protect against contagions—vaccines and antivirals.”

Matthew Frieman of the University of Maryland School of Medicine has been looking at repurposing FDA-approved drugs for diseases like SARS and MERS. He says that MERS researchers have been building their knowledge about how to treat and prevent the disease by using their history with SARS. That doesn’t mean that MERS has an economic backing beyond funding for research, however.

“I don’t think anyone thinks they are going to make a billion dollars off of a MERS drug,” says Frieman. “If you’re a company, that matters. As a researcher, I don’t care. I think the current Ebola outbreak may give a bump to the idea that having things stockpiled or at least the knowledge base there is important.”

Katze agrees. “The big pharma companies are not in the business of charity, so unless they have the money, they aren’t going to bother with a vaccine that isn’t important in this country,” he says. “The inadequacy of international response had nothing to do with research.”

Funding for diseases that largely affect low-income countries will depend mainly on funding from the government sector, according to IBISWorld healthcare analyst Sarah Turk. “The limited number of individuals that have Ebola, which is a significantly smaller market than many common illnesses like high blood pressure, has limited the number of pharmaceutical companies that are willing to invest in Ebola drugs,” she says in an email to TIME. “Once individuals take Ebola drugs, they will no longer make repeat purchases of Ebola medications, thus demonstrating the limited revenue potential for Ebola drugs.”

Turk says there’s a chance that the Ebola epidemic will lead to more organizations awarding prizes to drug manufacturers that can develop innovative drugs, and that the global nature of epidemics could incite international governments to share research and development subsidy costs. Those are hopeful scenarios for scientists working on treatments for the next big outbreaks of diseases.

“It’s a different world now. All these people who don’t want vaccines and don’t believe in global warming are going to be very surprised,” says Katze citing the rise of dengue fever, West Nile and chikungunya in southern U.S. states. “You can’t stop people or mosquitos from traveling, so you have to come up with a better response and be better prepared.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com