When Franklin National Bank collapsed 40 years ago on Oct. 8, 1974, it was more of a beginning than an end. A lurid tale of the bank’s downfall emerged over the next decade, involving mafia connections, ambitious Wall Street wannabes à la Jordan Belfort and a principal investor with a suspicious bullet wound in his leg.

More importantly, the bank’s demise was the first notable instance in which federal regulators helped a major bank wind down its operations in order to prevent global economic damage.

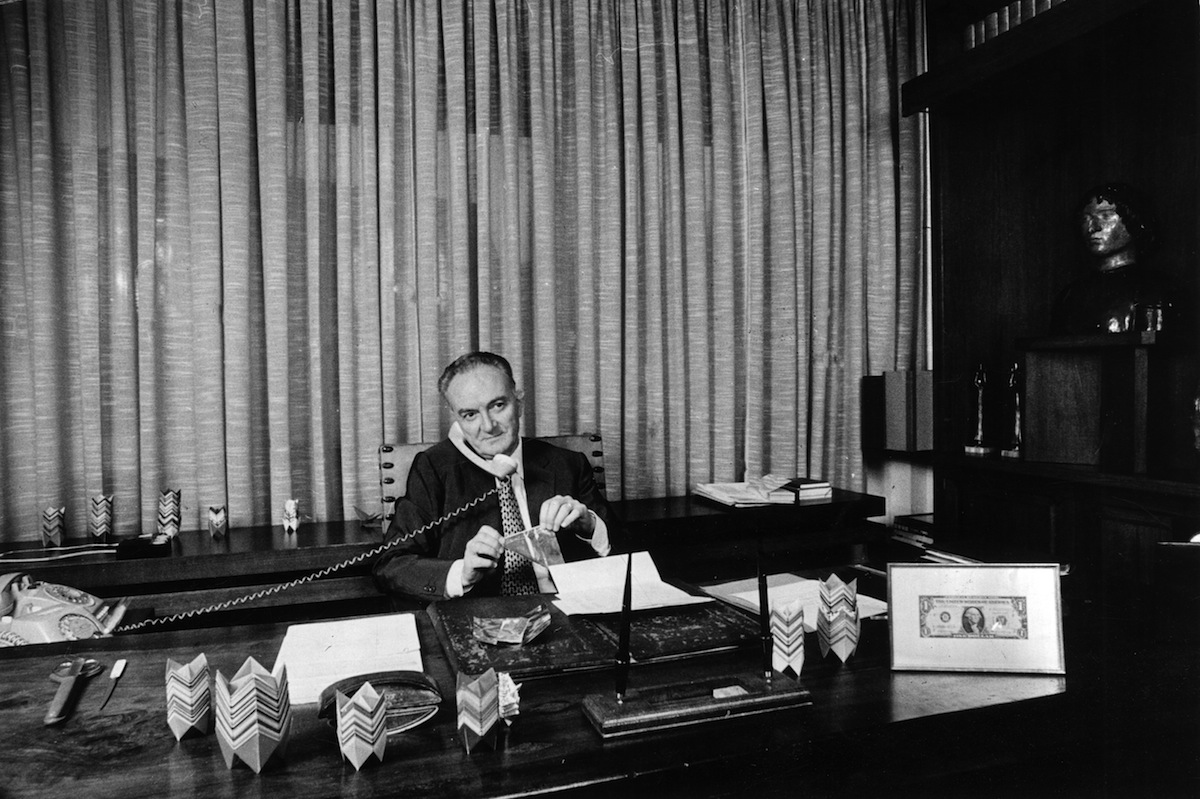

Franklin began as a humble Long Island bank with big-league aspirations. In the 1960s, the bank made questionable financial decisions to expand its operations and bum-rush the Manhattan banking scene. Franklin’s overzealous bankers bought a luxurious, too-large office on Park Avenue and sold a controlling stake in the firm to a shady Milan-based international financier, Michele Sindona.

The Sindona story reads like an American Hustle-style, stranger-than-fiction tale. In 1974, high-risk loans, ill-advised foreign currency transactions, and swings in foreign exchange rates caused Franklin to hemorrhage cash. The company lost $63 million in the first five months of 1974, more than any other bank in American history until that point. Not long after, the U.S. charged Sindona with illegally transferring $40 million from banks he controlled in Italy to buy Franklin National, and then siphoning $15 million from it. In August of 1979, just before his trial was about to begin, Sindona — who had ties to the Vatican and likely the Mafia — disappeared under mysterious circumstances; his family and lawyers got letters that “supposedly proved that he had been abducted by Italian leftist radicals,” according to TIME’s coverage of the episode. When he finally emerged after nearly three months — in a payphone booth near Times Square — he had what he said was a bullet wound in his leg. (Sindona claimed he was kidnapped by Italian terrorists but his defense later admitted it was a hoax, and Italian magistrates said that a secret Masonic lodge helped Sindona fake his own kidnapping.) He was sentenced to serve a 25-year prison sentence and died in prison by cyanide poisoning in 1986.

But the bigger story about Franklin National was the boring one. The bank, which was the 20th-largest in the U.S., was the first major financial institution whose wind-down was orchestrated by federal regulators. In 1974, the biggest questions federal authorities faced were how much it would damage the global economy if Franklin collapsed, and whether regulators should get involved.

Sound familiar?

It should: A similar crisis occurred in 2008 when the collapse of the largest American financial institutions seriously damaged the global economy. Much like Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, Franklin National was deeply enmeshed in the global economy. In both 1974 and 2008, federal regulators were in a position to take decisive action, but they responded in very different ways.

In 1974, as Franklin began to collapse, the Federal Reserve’s strategy was to lend it money in order to buy time for a bigger strategy, according to Joan Spero, author of The Failure of the Franklin National Bank: Challenge to the International. The Fed loaned Franklin a total of $1.75 billion, the largest bailout ever offered to a member bank at the time. Later, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation stepped in to help arrange a bank takeover. The FDIC set up negotiations with 16 banks, and a firm called European-American ultimately purchased Franklin for $125 million. The bottom line is that regulators helped to avoid an economic hit by lending Franklin money, and then smoothly transitioning the bank into a subsidiary of a functional institution.

“The entire financial world,” Arthur Burns, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, told TIME shortly after, “can breathe more easily, not only in this country but abroad.”

A very different scenario emerged in September 2008. The United States was on the cusp of the worst recession since the 1930s, and Lehman Brothers, the nation’s fourth-biggest bank, was in trouble. Granted, the problem was much more serious in 2008 than in 1974, and the stakes were higher — as would have been the size of the required bailout. The Fed ultimately allowed Lehman brothers to go bankrupt, and the economy seized up. (A sale to Barclays did look possible at the last minute, but it didn’t work out.) A litany of critics have suggested that the Fed should have orchestrated a Franklin National Bank-like wind-down for Lehman, and thereby could have prevented an international catastrophe.

“For the equilibrium of the world financial system, this was a genuine error,” Christine Lagarde, France’s finance minister at the time, said in the days after Lehman’s bankruptcy, reports the New York Times. Indeed, what followed in the U.S. was the worst recession since the Great Depression.

Still, federal regulators tend to come under a lot of fire when things go wrong — no matter what they do, which is kind of the point. Even in 1974, TIME criticized federal authorities for not being proactive enough with Franklin National Bank, despite its orderly purchase by European-American. In its story published in October of that year, TIME said federal authorities should have scrutinized Franklin and others more closely:

Faced with the failure of more than 50 federally insured banks in the past decade, the FDIC and other regulatory agencies need to keep a much closer watch not only on the roughly 150 banks on the FDIC’S “problem” list but also on virtually every bank in the nation. That way ailing banks will stand a better chance of being helped long before they reach a Franklin finale.

In other words, TIME’s message to federal authorities was: Be vigilant and act quickly. It’s a mantra we could learn something from today.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com