Isaacson, a former editor of TIME and an acclaimed biographer of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, among others, is the author of the new book Elon Musk

The rise of Bitcoin, the digital cryptocurrency, has resurrected the hope of facilitating easy micropayments for content online. “Using Bitcoin micropayments to allow for payment of a penny or a few cents to read articles on websites enables reasonable compensation of authors without depending totally on the advertising model,” writes Sandy Ressler in Bitcoin Magazine.

This could lead to a whole new era of creativity, just like the economy that was launched 400 years ago by the Statute of Anne, which gave people who wrote books, plays or songs the right to make a royalty when they were copied. An easy micropayment system would permit today’s content creators, from major media companies to basement bloggers, to be able to sell digital copies of their articles, songs, games, and art by the piece. In addition to allowing them to pay the rent, it would have the worthy benefit of encouraging people to produce content valued by users rather than merely seek to aggregate eyeballs for advertisers.

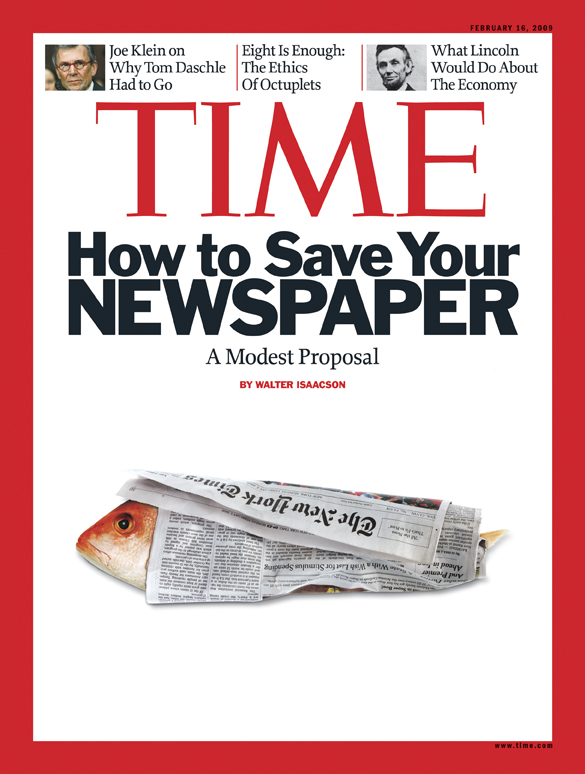

This is something I advocated in a 2009 cover story for Time about ways to save journalism. “The key to attracting online revenue, I think, is to come up with an iTunes-easy method of micropayment,” I wrote. “We need something like digital coins or an E-ZPass digital wallet–a one-click system with a really simple interface that will permit impulse purchases of a newspaper, magazine, article, blog or video for a penny, nickel, dime or whatever the creator chooses to charge.”

That was not technically feasible back then. But Bitcoin has now spawned services such as ChangeTip, BitWall, BitPay and Coinbase that enable small payments to be made simply, with minimal mental friction or transaction costs. Unlike clunky PayPal, impulse purchases can be made without a pause or leaving a trace.

When reporting my new book, The Innovators, I discovered that most pioneers of the Web believed in enabling micropayments. In the mid-1960s, Ted Nelson coined the term hypertext and envisioned a web with two-way links, which would require the approval of the person whose page was being linked to.

Had Nelson’s system prevailed, it would have been possible for small payments to accrue to those who produced the content. The entire business of journalism and blogging would have turned out differently. Instead the Web became a realm where aggregators could make more money than content producers.

Tim Berners-Lee, the English computer engineer who created the protocols of the Web in the early 1990s, considered including some form of rights management and payments. But he realized that would have required central coordination and made it hard for the Web to spread wildly. So he rejected the idea.

As the Web was taking off in 1994, I was the editor of new media for Time Inc. Initially we were paid by the dial-up online services, such as AOL and Compuserve, to supply content, market their services, and moderate bulletin boards that built up communities of members.

When the open Internet became an alternative to these proprietary online services, it seemed to offer an opportunity to take control of our own destiny and subscribers. Initially we planned to charge a small fee or subscription, but ad agencies were so enthralled by the new medium that they flocked to buy the banner ads we had developed for our sites. Thus we decided to make our content free and build audiences for advertisers.

It turned out not to be a sustainable business model. It was also not healthy; it encouraged clickbait rather than stories that were so valuable that readers would pay for them. Consumers were conditioned to believe that content should be free. It took two decades to put that genie back in the bottle.

In the late 1990s, Berners-Lee tried to create new Web protocols that could embed on a page the information needed to handle a small payment, which would allow electronic wallet services to be created by banks or entrepreneurs. It was never implemented, partly because of the complexity of banking regulations. He revived the effort in 2013. “We are looking at micropayment protocols again,” he said. “The ability to pay for a good article or song could support more people who write things or make music.”

These micropayment protocols still have not been written. But Bitcoin may be making that unnecessary. One of the greatest advocates of using Bitcoin for micropayments is the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, who as a student at the University of Illinois in 1993 created the first popular Web browser, Mosaic.

Originally, Andreessen had hoped to put a digital currency into his browser. “When we started, the first thing we tried to do was enable small payments to people who posted content,” he explained. “But we didn’t have the resources to implement that. The credit card systems and banking system made it impossible. It was so painful to deal with those guys. It was cosmically painful.”

Now Andreessen has become a major investor in companies that are creating Bitcoin transaction systems. “If I had a time machine and could go back to 1993, one thing I’d do for sure would be to build in Bitcoin or some similar form of cryptocurrency.”

Walter Isaacson, a former managing editor of Time, is the author of The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, out this week.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com