Years ago… they used to think you were Fu Manchu or Charlie Chan. Then they thought you must own a laundry or restaurant. Now they think all we know how to do is sit in front of a computer.

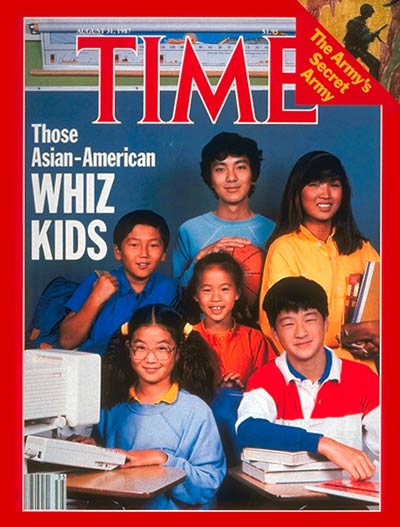

It was 1987 when Virginia Kee, then a 55-year-old a high school teacher in New York’s Chinatown, said the above words. She was one of several Asian-Americans who discussed the perception of their race for TIME’s cover story, “Those Asian-American Whiz Kids.” The cover story would elicit small-scale Asian boycotts of the magazine from those who found offensive the portrait of textbook-clutching, big-glasses brainiacs. To them, the images codified hurtful beliefs that Asians and Asian-Americans were one-dimensional: that they were robots of success, worshippers of the alphabet’s first letter, study mules branded with their signature eyes.

Today, Kee is 82. It has been nearly 70 years since the days when she avoided the public restroom “because it was white or colored”; nearly 20 years since she co-founded the Chinese-American Planning Council, then an unlikely social service for Asian-Americans, who were perceived to be sufficiently independent not to need it. And yet Kee, who still recalls the words she told TIME nearly 30 years ago, maintains that not much has changed.

“If you try to navigate the human part of it, we are seeing, as yellow people, our stereotypes still existing in the heads of many people. We don’t get the chance to really go through and break the glass ceiling,” Kee says. “We are putting limitations on our people.”

The longevity of the idea that “all [Asian Americans] know how to do is sit in front of a computer” was highlighted recently when several top technology firms released their first-ever diversity reports. Those reports and media discussion of their findings centered on the obvious, important problem: an under-representation of women, blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans. Very little was said of the discrepancy between the high percentage of Asian tech employees and the disproportionately low percentage of Asian leaders. The fact that Asians’ presence charted in bars more than a few pixels tall, it seemed, disqualified them from scrutiny.

To compare representation across companies, and in tech versus leadership roles, use the drop-down menu.

“There is an important conversation to be had in terms of who actually has full access to education and economic opportunities,” says Mary Lui, a professor of American and Asian-American Studies at Yale University. “But at the same time, think about what [not talking about Asian representation] might be saying in terms of Asian-Americans in the U.S.”

What it says is this: Asians and Asian-Americans are smart and successful, so hiring or promoting them does not count as encouraging diversity. It says: there is no such thing as underrepresentation of Asians and Asian-Americans. The problem with this belief, historians and advocates assert, is that it not only obscures the sheer range of experiences within Asian and Asian-American populations, but also excludes them from conversations about diversity and inclusion in leadership and non-tech sectors.

*

Not that this exclusion is a new phenomenon. Historians agree that diversity has turned a blind eye to Asians and Asian-Americans ever since the 1965 Immigration Act. With the conclusion of World War II, many ex-colonial Asian countries like the Philippines, South Korea and India had emphasized technical education to modernize and industrialize their new national economies. The Immigration Act permitted the migration of those highly educated Asians as a means of recruiting science, technology or engineering experts to the U.S. during the Cold War era.

For over half a century, the growth of the Asian-American population in the U.S. had been stunted, first by racially-motivated exclusionary laws that banned Asian immigration and later by annual quotas. But within years of the 1965 act, that population boomed. By the 1970s and 1980s, the image of Asian-Americans was no longer of the alien invaders washing ashore in California during the Gold Rush, the faceless bachelors laying the cold steel of the Transcontinental Railroad, or the land-grabbing and job-stealing migrants. The new Asian-Americans were scientists, doctors, programmers and engineers. They were thriving.

By the mid- to late-1980s, the notion of Asian-Americans as universally successful was everywhere. Major news organizations lauded them as the “model minority” — a term first coined in 1966 when first the New York Times and then U.S. News and World Report published stories that suggested Asian-Americans, through their steely work ethic and quiet perseverance, were uniformly triumphant despite prejudice. The idea elicited criticism, particularly from Asian-American groups whose problems were made invisible behind the guise of universal success: the displaced Laotian and Cambodian refugees of the Vietnam War, or the elderly Filipinos fighting to save their low-cost I-Hotel housing complex from urban renewal.

TIME was not immune to the model minority craze. In 1985, two years before its controversial cover story, TIME published an article called “To America With Skills: A Wave of Arrivals From the Far East Enriches the Country’s Talent Pool.” The piece documented the flood of Asian-Americans into high-paying careers and elite universities with decidedly less focus on marginalized groups like poor Chinese launderers, unassisted Vietnamese refugees or underpaid South Asian cab drivers:

What really distinguishes the Asians is that, of all the new immigrants, they are compiling an astonishing record of achievement. Asians are represented far beyond their population share at virtually every top-ranking university: their contingent in Harvard’s freshman class has risen from 3.6% to 10.9% since 1976 … Partly as a result of their academic accomplishments, Asians are climbing the economic ladder with remarkable speed.

“I consider it a two-headed hydra: the stereotype of being the evil invader, or the model minority,” says Helen Zia, an Asian-American activist, journalist and historian. “The conclusion of both is the same. Asian-Americans are too foreign — from the outside, being an invader, or on the inside, being so bland and so good.”

Asian-Americans’ visible success, with numbers to prove it, began to mean they should be excluded from inclusionary practices like affirmative action. More severely, Asian-Americans were seen as a hindrance to diversity. In one case, high school senior Yat-Pang Au and his Hong Kong-born parents filed a formal complaint to the U.S. Department of Justice that the University of California admissions system discriminated against Asian-Americans. Au’s case was profiled in several media organizations, including TIME’s 1987 “Whiz Kids” cover:

A straight-A student, Yat-Pang, 18, lettered in cross-country, was elected a justice on the school supreme court and last June graduated first in his class at San Jose’s Gunderson High School. Berkeley turned him down. Watson M. Laetsch, Berkeley’s vice chancellor for undergraduate affairs, insists that Yat-Pang was rejected only for a ”highly competitive” engineering program.

Au is now 45. He still recalls his parents’ insistence that he “fight for his rights,” a struggle that concluded with an apology from the chancellor. He later transferred to UC Berkeley in 1989 for his junior year after two years at DeAnza College, a community college in the San Francisco Bay Area. Today, he is the CEO and co-founder of Veritas Investments. And though Au managed to find success despite obstacles — the classic model minority narrative — he says that the fact he chose entrepreneurship as a career meant he rose to leadership despite these systems that assume success for Asians is a byproduct of their race.

“I was, to be honest, embarrassed that I didn’t get in, embarrassed thinking and expecting that we lived in a relatively color blind society,” Au said.

Today, it appears that Asians and Asian-Americans still pose a threat to diversity. Only now even they believe the idea, too. In 2012, a popular New York Times op-ed titled “Asians: Too Smart for Their Own Good?” described Asian-American college students feeling like “a faceless bunch of geeks and virtuosos.” The previous year, an Associated Press article reported that many Asian-Americans were no longer checking off the “Asian” box on college applications, in order to circumvent unspoken quotas at top colleges. Their threat to diversity is so convincing that Asians and Asian-Americans have begun to offer what is, at its core, an inadvertent apology.

*

As the world’s response to the tech diversity reports shows, Asians and Asian-Americans remain invincible to underrepresentation: even though companies tend to have disproportionately low levels of Asian leaders compared to the number of Asians in technical jobs, this discrepancy is overlooked. That silence is only one part of a larger issue that experts insist has deep historical roots. It is not simply a first-world complaint or an upper-middle class problem. It is one with sobering consequences.

“Being the model minority, there’s the expectation that you’re going to do so well you shouldn’t have any problems,” Zia says.

The belief in a blanket Asian-American culture is so thick that it has resulted in confusion when Asian-Americans deviate from the model minority myth. Today, diversity is more visible than ever: There is the commanding John Cho, and there is the awkward William Hung; the funny Mindy Kaling and the serious Indra Nooyi; the talkative local launderer and the mum evil villain; the whitewashed American-born Chinese and the perpetual foreigner. And yet those who display that diversity are often perceived as exceptions. The rule is the single framework — the model minority myth — that persists as the dominant stereotype for the whole race, especially in the tech sector.

“If [executives] assume their Asian-American tech employees are the model minority,” Zia continues, “the baggage that that also brings is that they are good, high-tech coolies who will do their jobs, work like hell, stay up 24/7 grinding out code — and that [executives] can never think of promoting them into management or leadership positions.”

Yet the movement to push Asians and Asian-Americans into conversations of diversity and inclusion has fizzled out in recent years. Asian-American activism, historians believe, was at its peak following a national outcry after two white men escaped prosecution for their 1982 racially-charged murder of Chinese-American Vincent Chin. Nascent groups like American Citizens for Justice and the Coalition Against Anti-Asian Violence demanded equal treatment of Asian-Americans both under the law and in society. The fight for Asian-American equality may be less fierce today, but it is still there.

“I wanted to bring to the conversation that Asians, although they were starting to enter the ranks of these companies, were not moving to the top of these organizations. I think it’s still the case that organizations are still not focused on the issue,” says Korean-American leadership consultant Jane Hyun, whose book Breaking the Bamboo Ceiling: Career Strategies for Asians discusses caps on Asian-American seniority in corporate settings.

The onus, Hyun says, is not only on society and business, but also on Asian-Americans themselves. They must try to untangle how cultural, historical and social factors inhibit their progress, in leadership or in other areas where Asian-American diversity is needed, like film, TV and politics. J.D. Hokoyama, former president of the national nonprofit Leadership Education for Asian Pacifics (LEAP), adds that “[The problem] is not just from the top. Our own communities are also settling.”

The irony is that it is the pride of many Asian and Asian-American cultures not to settle for anything less than they deserve. Unless, that is, they or everyone else believe they’ve already gotten what they deserve, and more: academic success, financial stability, happiness. It is hard to imagine that some have not gotten what they deserve, especially in an age when diversity in Asians and Asian-Americans is seen as the difference between straight-laced, straight-A geniuses and lazy, A- slackers. There are still those facing deeper problems that are dismissed or overlooked. And what it takes to start unraveling these issues is simply to understand that some things are too good to be true.

“We have the good, the bad and the ugly. We’re not models,” Zia said. “We should we be seen in our full humanity. That is, in my experience, what everyone really aspires to.”

Read next: Why I Changed My Korean Name—And Why I Changed It Back

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com