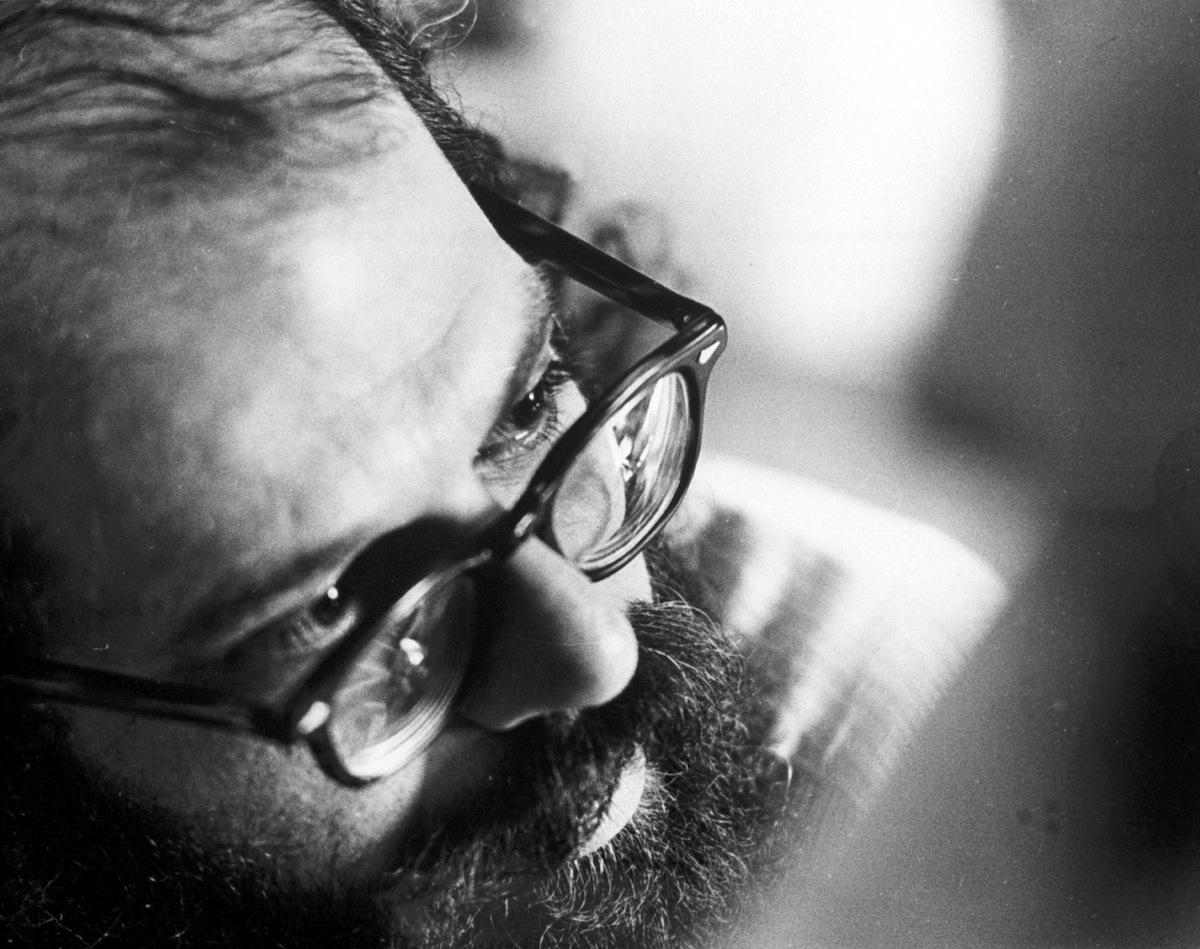

Before Allen Ginsberg invoked the ire of authorities with the frank (and frequent) depiction of sexual acts in “Howl” — “in empty lots & diner backyards, moviehouses’ rickety rows, on mountaintops in caves or with gaunt waitresses in familiar roadside lonely petticoat upliftings & especially secret gas-station solipsisms of johns, & hometown alleys too” — he stunned a crowd of drunk poetry fans at San Francisco’s Six Gallery.

On this evening in 1955, Oct. 7, Ginsberg performed the piece in public for the first time at a poetry reading which had been advertised by a postcard proclaiming: “Remarkable collection of angels all gathered at once in the same spot. Wine, music, dancing girls, serious poetry, free satori.”

The wine and the satori — deep understanding, in the zen sense — went hand in hand. In his novel The Dharma Bums, Jack Kerouac fictionalized the event with a description of circulating gallon jugs of California burgundy among the increasingly raucous crowd, “getting them all piffed so that by eleven o’clock when Alvah Goldbrook [Ginsberg’s stand-in in the novel] was reading his wailing poem ‘Wail’ [‘Howl’] drunk with arms outspread everybody was yelling ‘Go! Go! Go!’”

Those who were there said the reading felt like a revolution — poet Michael McClure said that it pushed the art form past the “point of no return” — but critics gave the poem mixed reviews. The poet James Dickey called it “a whipped-up state of excitement,” but scolded that “it takes more than this to make poetry.” Poet and critic Paul Zweig was more reverential, saying that “Howl,” “almost singlehandedly dislocated the traditionalist poetry of the 1950s.”

Government officials, meanwhile, found it intolerably vulgar. When it was published about the year after that first reading, U.S. Customs agents seized Howl and Other Poems when it arrived from its London-based printer on grounds that it was indecent and obscene; San Francisco police arrested Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who published it, and Shigeyoshi Murao, manager of City Lights Books, who sold it.

Mid-century America simply wasn’t ready yet for Ginsberg’s offer of free satori, it seemed. In 2007, on the 50th anniversary of the poem’s obscenity trial, Ferlinghetti told the New York Times he believed the charges were related less to the poem’s four-letter words than to the revolutionary ideas it expressed.

A San Francisco judge (and Sunday school teacher) later exonerated both the men and the poem, ruling that Howl had “redeeming social importance.” He may not have supported its ideas, but he was a stickler for self-expression: “Would there be any freedom of press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid innocuous euphemism?” the Times story quotes from Judge Horn’s 1957 opinion. “An author should be real in treating his subject and be allowed to express his thoughts and ideas in his own words.”

Hindsight would confirm the judge’s wisdom. In 1985, TIME’s R.Z. Sheppard noted that, “the man once feared as a weevil in the nation’s moral fiber is in a disarming state of equilibrium. Cultural norms have adjusted in Ginsberg’s favor since 1956, when he disturbed the peace with Howl.”

Read the 1985 piece about the poet, here in TIME’s archives: Mainstreaming Allen Ginsberg

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com