This story originally appeared on xoJane.com.

I am on a fun first date in the trendy Andersonville neighborhood of Chicago. After Thai food, we go to get sundaes. Since he bought lunch, I order dessert. The cashier asks for a name for the order. “Jae – J-a-e.” “Thank you, Jae.” My date asks me, “is Jae short for anything?”

This is new for me. Not the get-to-know-you questions, the pad thai or ice cream, but my name. For the past nine years, I went by “Daphne,” a name I picked. Pretty much everyone in my life, apart from my family, met me as “Daphne.” On July 9th, 2014, I sent an electronic letter to pretty much everyone I know, explaining that I would like to be called “Jae.”

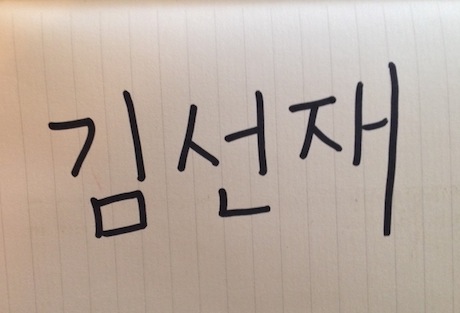

My Korean, given name, on my passport, college diploma and all other official documents, is Seonjae Kim. Like many Korean names, it is based on Chinese characters. Composed of two syllables, “Seon” (pronounced more like Sun) means “to give, to be generous” and “Jae” means “to be” or “to exist.” While “Seon” is more commonly found in female names, “Jae” is more commonly found in male names.

Growing up in Seoul, South Korea, I loved my name. My name isn’t common, and I loved its unusualness and its androgyny. It made me feel powerful. Before the inevitable self-doubt that takes over young girls as they become women, and before I realized that many things about my home country were oppressive, I was happy. Then, I wasn’t, so I left. (Why is a whole another story – it’s just that many of us don’t belong to where we come from.)

My first pit stop in America was 7th grade in a small private school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This turned out to be one of those nightmarish pre-teen years, growing pains only doubling with culture shock. My name, in the middle of all that, was a token of the sense of alienation I felt. Butchered in foreign tongues, “Seonjae” did not have the beauty and power that accompanied it back in Seoul. I had trouble making friends, and struggled with math and science. Art – encountered through books and the Internet – was my escape. I wrote in journals, dreamed about being an artist in a big city, and planned to do whatever it took to become that person.

Although “switching out” an ethnic-sounding name for an American name that’s easier to pronounce is common practice, I feel the need to differentiate my narrative. Becoming Daphne wasn’t about making things easier, but a desire to be someone else entirely – both Korean and American, or perhaps, neither.

At one summer camp in elementary school, I took a Greek mythology class, a subject I loved as a child. The name Daphne jumped out at me from the myth of Apollo and Daphne. I didn’t think about the themes of the tale, or the fact that this was a decision that would affect the rest of my life, just how exotic, feminine and lovely the name sounded. My parents, perhaps exasperated from my growing adolescent angst, supported my youthful determination. When my family moved to Northern Virginia and I started 8th grade, I was known as Daphne.

The following years were nothing short of wonderful. My life moved slowly uphill to joyful young adulthood. I had an exceptional high school and college education, loving friends and inspiring mentors, and most of all, the chance to become an artist. My name gave me the confidence to direct plays, write poems, be a student leader, churn out application after application, throw themed parties, and generally, be fabulous.

But along the way, I started feeling fragmented, compartmentalized, and inauthentic. I put too much faith into my own American Dream, which was that I held absolute control over who I could become, all the time, about anything. When I wasn’t who I aspired to be, when I felt held back by my body, skills or emotions, I felt like a failure, because Daphne wasn’t supposed to fail. As I felt more and more disconnected from my physical home Seoul, I felt like I existed in a vacuum of my own created identity, “home” an elusive feeling I searched for in endless projects, parties and anywhere I could belong to for a little bit.

The name came to me one warm day sometime around late April, so obviously truthful that I could not believe it had never occurred to me before. It was one that sounded beautiful in both languages. One that had always been a part of my given name.

I casually started talking to friends about my new name, like a joke, like a half-formed idea. But my inner clarity on the issue was solid from the very first impulse. Unlike other decisions I was constantly tempted by but couldn’t ultimately bring myself to do, like moving to San Francisco or dying my hair blue, I never truly doubted “Jae.” Perhaps because it wasn’t really a change – just a coming home.

A few weeks before graduation, I participated in a tradition with my college theatre board, an event in which the graduating seniors gather with some other friends and make a piece of theatre in 24 hours. While brainstorming, we landed upon the theme of “myth.” We decided to go around and share a “myth about ourselves that wasn’t true anymore” as we approached the end of our college years.

In front of some of my dearest people, I talked about my name. Why I changed it in the first place and why I wanted to let it go. How I had found inspiration in the oddest of places: the Korean American playwright Young Jean Lee, the character of Queequeg in “Moby Dick,” my friend Natalie’s gorgeous thesis performance, a feminist retelling of the character Caddy in “The Sound and the Fury,” my part-time job as a Korean translator that made me reconnect with my mother tongue. All these things, independent of one another, seemed to be pouring one beam of clarity into me.

My name had become a breeding ground for other “myths” about myself, some useful, some destructive. I had to realize that they were just that: myths. Like the story of Apollo and Daphne, they would never be true, even if they were beautiful.

I don’t want to to feel like that anymore. I graduated from college last month, and I am moving to New York City in the fall to pursue theatre. As I start this exciting new chapter, a life I only dreamed of as a lonely preteen, I need to eliminate the things in my life that feel inauthentic, even if I love those things with complicated emotions.

My chosen name is one of them. I know it sounds pretty. I know it fits me. I am grateful to it for letting me become who I am. But it’s time to find a more solid home within myself. I don’t want to distance myself from home, and at the same time, I want to be someone different from who I was expected to be. Jae is a name that honors my heritage and my family as well as my own agency to be who I am.

When I finally felt ready, I wrote an email to the people in my life. After clicking “send” to more than a hundred people, I jumped in the shower to wash off any chance of second-guessing. By the time I put myself in a towel, my inbox was already blowing up. The responses were overwhelming and moving, from my college friends, collaborators and mentors, to high school friends and teachers I hadn’t talked to in years. Some of them even shared with me their own stories, like my friend Gavi, who taught me a thing or two with her beautiful notion of home:

Today I toyed with the decision to break Kashrut (keeping Kosher) in order to try food made by a food network star, and decided not to. I walked away as they served the beautiful dishes he made to waiting spectators. Little things connect us to “home” which is not always a place but instead a set of values, traditions and memories – names are little things, little connectors, that mean more than the letters they contain… I didn’t begin observing the laws of Kashrut (albeit loosely) because I think eating Pork makes me a worse person or will result in X or Y divine punishment. I began so that I could feel connected with that “home” every day, all day, constantly, every time I eat or think about eating.

Indeed, in my new name, I feel home. The departure from “Seonjae” to “Jae” makes much more sense than to “Daphne.” I no longer experience confused looks when I present my ID. My friends are slowly but surely getting used to my new name. But really, I am the person they know, just one less mask. I know I’ll never be able to be completely myth-free. There will always be the pressures of fiction, the promise of media and self-help books that the “perfect” me is somewhere else. But my name, instead of a pretty crutch, is a reminder to bring it back to myself, my internal home, with all its baggage.

I’m not sure what to do with “Daphne.” Right now, it occupies my Facebook, website and directing resumé as a sort of adopted middle name, an artifact honoring the time I spent with it. “I think the three name thing is badass,” my friend Brandon says, and he’s right, I do love it. But a part of me is itching to let go. A part of me wants to include my mother’s last name, “Noh,” into my name. My journey has encouraged me to not blindly accept but actively question who I can choose to be on a daily basis – we are neither pre-determined products of our heritage nor perfect malleable blank slates. So perhaps one day, I will call myself something else, or be someone I cannot imagine right now, as I grow bigger and dig deeper.

But, for now, I’m good with Jae. J-a-e. The part of my name that means “to be.”

Jae Kim, a recent graduate of Northwestern University, is originally from Seoul, South Korea.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com