You may have downloaded the newest iOS 8 operating system to your iPhone recently, giving you lots of additional options. The Air Force is doing the same to its F-16 fighters. In fact, its new M6.2+ Operational Flight Program gives those fighter pilots an especially nifty new feature: it keeps them from flying into the ground and killing themselves.

The Air Force has long expressed concern over the fact that the leading cause of fighter-pilot deaths is when perfectly-operating aircraft simply fly into the ground because of poor weather, pilot distraction, or unconsciousness due to extreme maneuvers that can drain the blood from a pilot’s brain. This tendency even has its own grim acronym: CFIT (pronounced see-fit), for “controlled flight into terrain.”

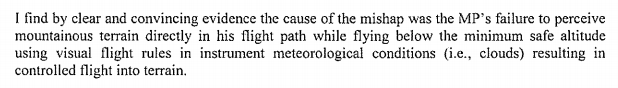

Too often, Air Force accident-investigation boards have ended like this one last year in Afghanistan (“MP” refers to the “mishap pilot”):

The Air Force estimates that CFIT has killed 75% of the 123 F-16s pilots—92—lost since the first fatal F-16 crash in 1981. But the software upgrade should sharply reduce such accidents. “This is a significant development and will save lives,” says retired Air Force lieutenant general David Deptula, a fighter pilot with more than 3,000 flight hours, including 400 in combat. The system is likely to be added to the service’s F-22 and F-35 warplanes.

The Air Force began grappling with the problem 25 years ago, but crashes persisted. “By the early 1990s, several F-16 mishap boards had made strong recommendations that such systems be installed,” says Alan Diehl, a longtime Air Force safety expert, now retired. “But these recommendations were always rejected by senior Air Force leaders.”

The push to do something finally kicked into high gear in 2003, when Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld challenged the military to cut its accident rate in half. “World-class organizations,” he told the Air Force and the other services, “do not tolerate preventable accidents.”

But more training could only accomplish so much. “Reductions in the [CFIT] rates have long been stagnant and no large improvements from training are envisioned for the future,” an Air Force report said in 2006. “The human being is now the limiting factor because he or she cannot always recognize a warning or respond appropriately to prevent a mishap.”

That’s when the Air Force, with help from NASA and F-16-builder Lockheed Martin, got to work on the robo-pilot now being installed on F-16s (109 already have them, and all 631 are slated to by next summer, according to Air Force spokesman Daryl Mayer. The fix is not planned for the 338 F-16s built before 1989 that lack digital flight-control systems).

Here’s how it works: when an F-16’s sensors and digital map detect that the plane is getting too close to the ground, an alarm sounds. It is triggered by a complex formula involving speed, trajectory—and what might be just ahead. The alarm goes off when the plane is in a place where a 5 G escape maneuver would be needed to avoid crashing into the ground (the F-16 can maneuver at up to 9 Gs, or nine times the force of gravity. That can make a 20-pound head feel like 180 pounds, and makes for a very stiff neck for passengers flying in the back seat of a two-seat F-16 trainer).

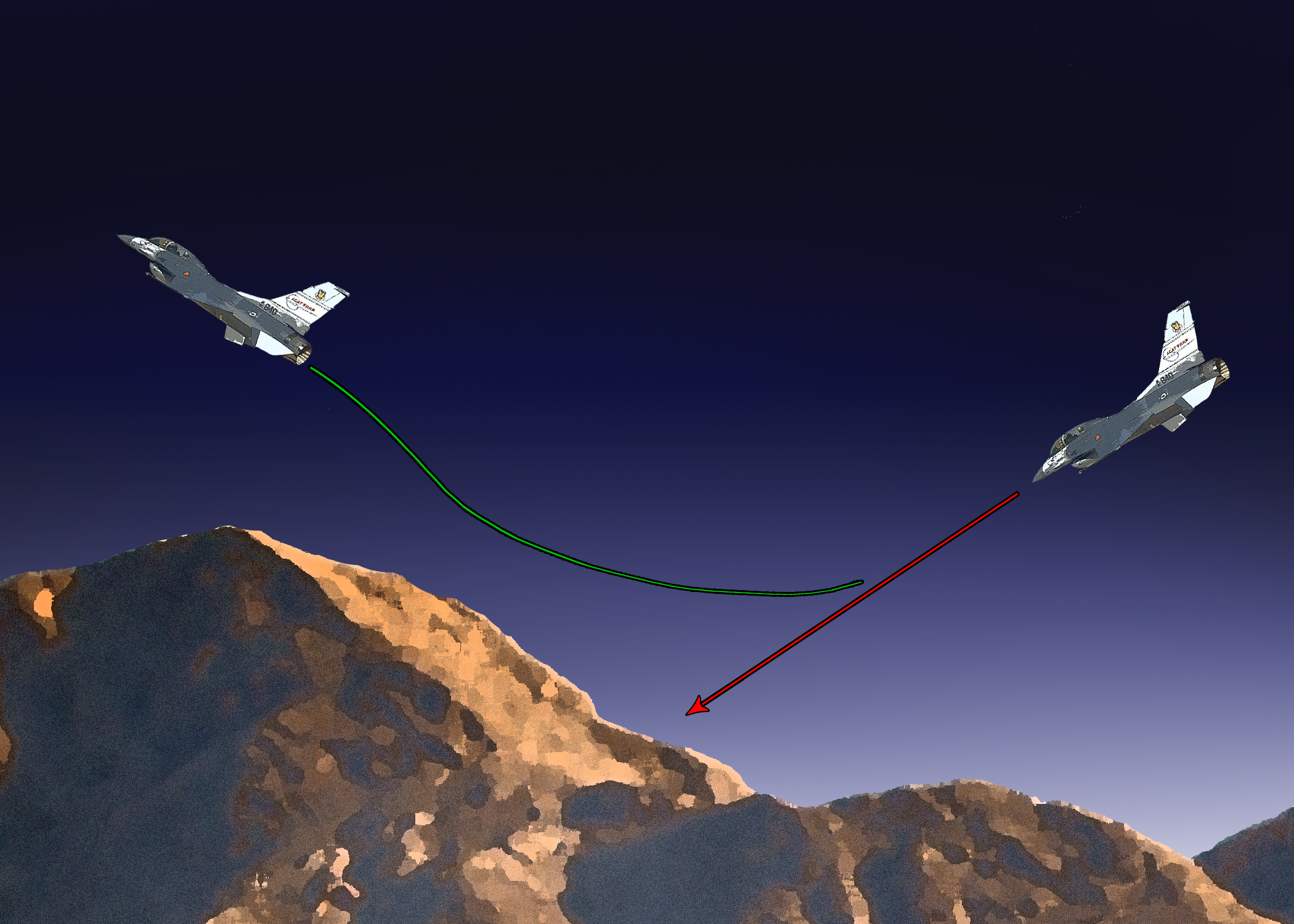

Shortly after the alarm sounds—the duration depends on the flight’s specifics—the plane’s “Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System” takes over. It quickly rolls the plane upright and pulls it upward, away from the ground. The pilot can reassert control of the plane at any time; the software is designed not to interfere with low-level bombing or strafing runs.

In the past, such alarms would sound—but it was up to the pilot to respond to the warning. At high speeds close to the ground, a delayed response can be deadly, as apparently was the case in that 2013 crash in Afghanistan. “Prior to impact, the mishap aircraft provided low-altitude warnings,” the probe said. “However the mishap pilot did not take timely corrective action.”

Too often, the pilot’s attention has been “channelized”—so focused on completing a demanding maneuver—that while the alarm may be heard, it is unlistened-to. Combined with frequent false alarms, the alarm-only setup hasn’t made a major dent in CFIT accidents.

The Air Force believes the new software will reduce the number of perfectly-fine F-16s flying into the ground by 90%. The service has estimated that could save 14 jets, 10 pilots, and more than a half-billion dollars in hardware.

But it’s also going to save something impossible to calculate. “From the human standpoint, nothing destroys morale like losing a squadron mate and friend,” Lieut. Colonel Robert Ungerman said two years ago, during development of the software upgrade at California’s Edwards Air Force Base. “The prevention of CFIT mishaps will avoid that anguish for dozens of spouses, parents, and children of lost pilots.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com