Charisma is a word, like thunderstorm or orgasm, which sits pretty flat on the page or the screen compared with the actual experience it tries to name. I don’t recall exactly when I first looked it up in the dictionary and read that charisma is a “personal magic of leadership,” a “special magnetic charm.” But I remember exactly when I first felt the full impact of the thing itself.

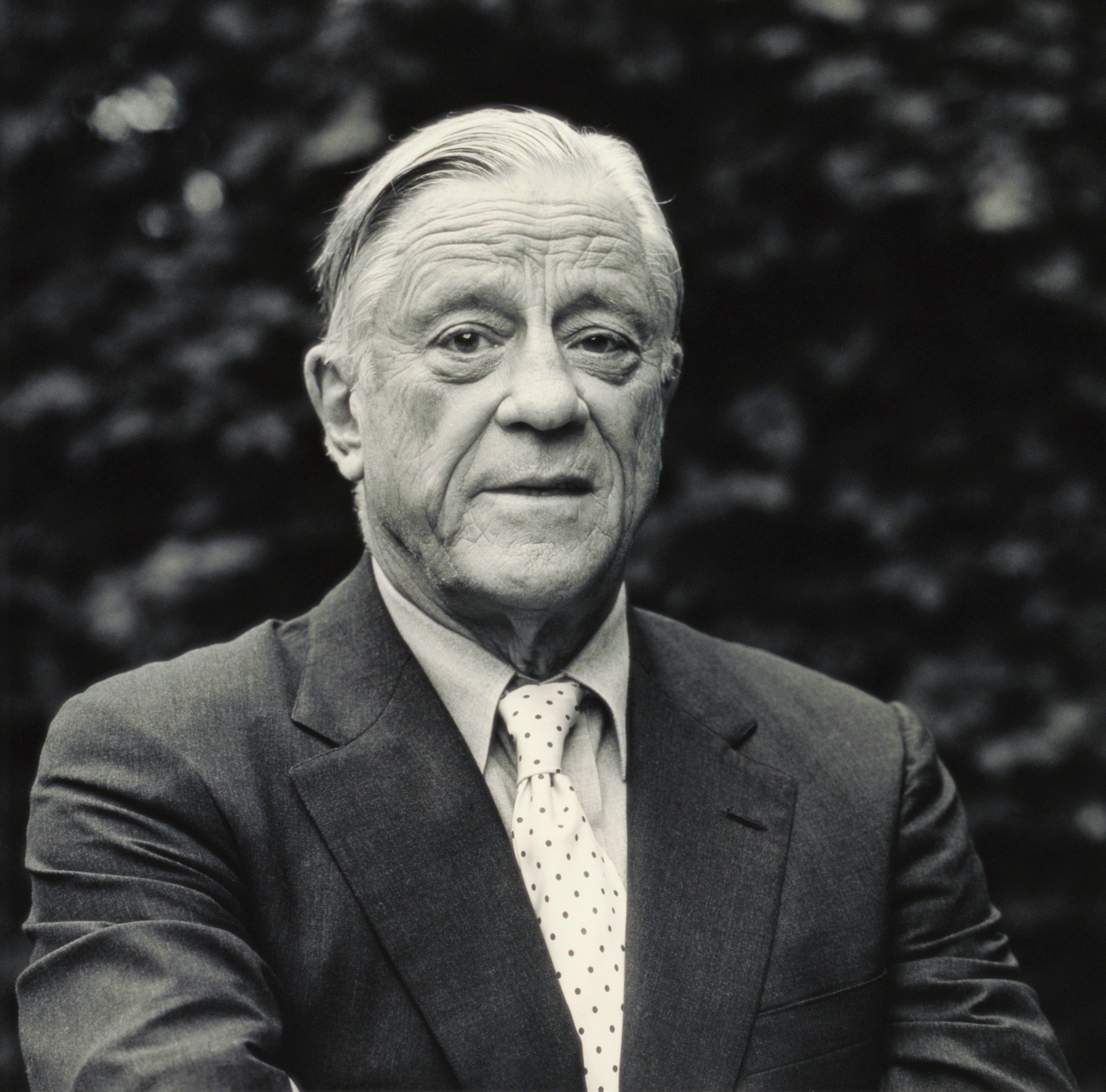

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was gliding through the newsroom of the Washington Post, pushing a sort of force field ahead of him like the bow wave of a vintage Chris-Craft motor yacht. All across the vast expanse of identical desks, faces turned toward him — were pulled in his direction — much as a field of flowers turns toward the sun. We were powerless to look away.

This was after his storied career as editor of the Post had ended. I was the first reporter hired at the paper after Bradlee retired in 1991 to a ceremonial office on the corporate floor upstairs. For that reason, I never saw him clothed in the garb of authority. He no longer held the keys to the front page and the pay scales, so his force didn’t spring from those sources. Nor did it derive from his good looks, his elegance or his many millions worth of company stock.

I realized I was face to face with charisma, a quality I had wrongly believed I understood until Bradlee reached the desk where I was sitting and the bow wave pushed me back in my chair. It is pointless for me to try to describe this essence, because in that moment I realized that it cannot be observed or critiqued. Charisma can only be felt. It is a palpable something-more-ness — magical, magnetic — as rare as the South China tiger. I’ve met famous writers, directors, actors, athletes, billionaires, five Presidents of the United States, and none of them had it like Bradlee.

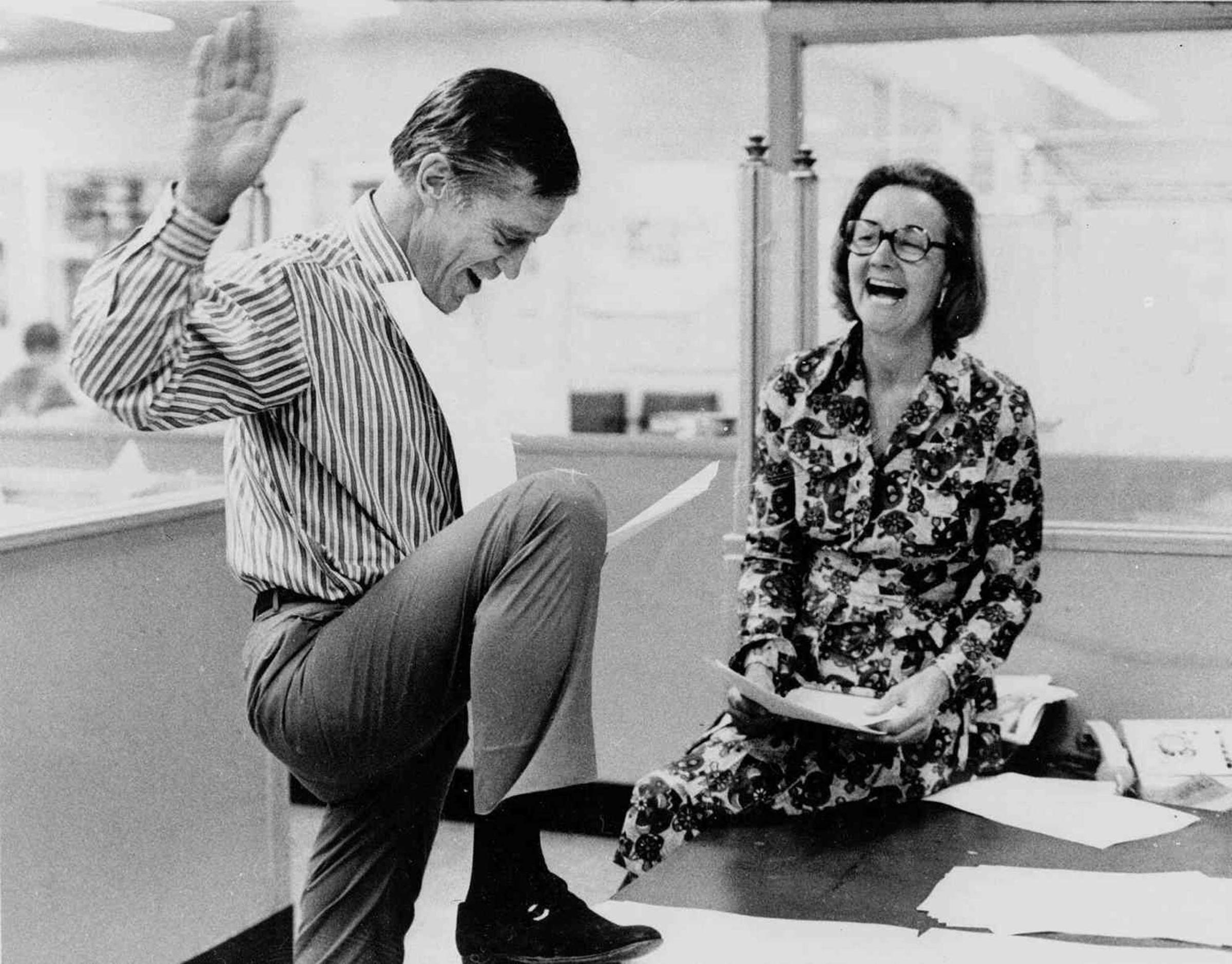

Photos: Benjamin Bradlee's Life in Pictures

Which made him an odd fit, in a way, for the newspaper business. Set aside, for the moment, the improbable heroics of Watergate and the Pentagon Papers, which would never have happened as they did without the peculiar protagonist Richard M. Nixon. The overwhelming bulk of the newspaper life is forgettable stories cranked out in mediocre fashion, the latest snowstorm, ballgame, traffic accident, charity dinner, Senate election, drought, chicken recipe. Having Bradlee sit down at your table in the Post’s lunchroom, where he often dined with the troops amid the plastic trays and sad salads, was like having Sinatra plop down beside you at a Trailways bus station. Great stuff, but you couldn’t help thinking that something was being squandered, that he really ought to be elsewhere, bedding Grace Kelly at the Hotel Hermitage in Monaco, or stealing the Mona Lisa, or outwitting Dr. No.

Ordinary news hacks — even the best of them — do not pal around, as Bradlee did, with John F. Kennedy and Lauren Bacall. They do not, as Bradlee did, arrange the sale of Newsweek by the Astors to the Grahams. They do not, as Bradlee did, have a sister-in-law whose mysterious death prompts a clandestine visit from the CIA’s top spymaster, desperate to retrieve her diary. They do not, as Bradlee did, live in a mansion that once belonged to Abraham Lincoln’s son.

Yet Ben wore all this with impossible ease, just as he wore his handmade shirts from London’s Jermyn Street as casually as a mortal wears Land’s End. God, those shirts — as beautiful and numerous as Gatsby’s, but minus the stain of anxiety. Only three types of men wore shirts like that: toffs, posers and Ben.

Anyway: impossible ease. He sized people up in an instant (of one failed job applicant he growled simply, “nothing clanks when he walks”) and met them as they were. He was the same fellow chatting with a movie star as he was with my father-in-law, a retired electrician with whom he swapped stories of card games in the Navy. When I introduced him to my nephew, another Benjamin, he bent to look the boy in the eye and said in a brotherly tone, “They can call you Ben, and they can call you Benjamin — but don’t ever let ’em call you Benjie!”

What made Bradlee a great newspaperman was that he had exactly the right blend of intelligence and impatience, plus an infectious hunger to be in the know. Feeding Ben a good bit of gossip was like turning over the last card of an ace-high straight, with his wide-eyed smile as the payout. He also had a restless attention span, so his reporters vied relentlessly to find stories sexy and important enough to catch and hold his interest. Whole sections of the Post went almost entirely unnoticed by him — his response to news that the paper’s dance critic had won the Pulitzer Prize was “Who the hell nominated him?” But the parts of the paper that Bradlee cared about were bright, bewitching and boffo.

(Ben had a thing about ballet coverage. He once summed up his animus toward the New York Times by noting, “it’s a paper with four f-cking dance critics!”)

As Shakespeare would appreciate, these gifts had a downside, and when it was revealed Bradlee experienced the low point of his career. A reporter named Janet Cooke decided to dazzle the editor with an invented story, because she couldn’t find a real one hot enough to do the trick. Plenty of people, inside and outside the newsroom, were skeptical of Cooke’s tall tale of an 8-year-old heroin addict with no last name and rather stilted diction. They noticed that the story was untethered by geography, dates and on-the-record sources. But Bradlee believed in it, and he was all that mattered, bigger than all the skeptics, bigger than the fail-safes, bigger even than the Pulitzer committee that awarded Cooke a prize for feature writing. The prize had to be returned when the lies unraveled.

It was around that time, 1981, that young Don Graham, successor-in-waiting to his remarkable mother, Post publisher Katharine Graham, clearly realized that there would never be — could never be — another Bradlee. Plenty of wannabes stalked the newsroom, wearing bespoke shirts and trying to copy Ben’s way of snarling out cuss words while grinning incandescently. When it came time to anoint Bradlee’s successor, however, Graham passed over all of them in favor of an unglamorous Midwesterner. Len Downie did not push out a bow wave. He was, in some ways, the anti-Ben. But if there was a better all-around newspaper editor, I don’t know who it was.

Ben sailed on as the one and only. In his later years, he groused amiably that he was just a museum piece, his office merely another “stop on the tour” of the Post. As newspaper circulation and profits sank year after year, Bradlee never indulged in second-guessing or armchair quarterbacking — petty pastimes that would have been beneath him. Though he was the most celebrated newspaper editor of his lifetime, perhaps the most celebrated of all time, he pronounced himself baffled by the competitive pressures of the digital age, and thankful that his era was the era of expansion and wealth.

I’m thankful too. For only the adrenaline charge of those go-go years, the generation after World War II, could have drawn such a man to the newspaper game. And the fact that Ben Bradlee was a part of it, never mind the prizes and the books and the movies — just the fact of Bradlee, the force, the charisma, threw an electric glow over the whole business and made it a joy to go to work. Though his ship passed over the horizon, he left a luminous trail dancing in his wake.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the location of the London shirtmaker where Bradlee ordered his dress shirts. It was Turnbull & Asser on Jermyn Street.

Read next: Jill Abramson: Ben Bradlee Was Luminescent

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com