By the morning of February 6, 1990, I’d been living on a fine edge for more than a decade, always courting disaster to experience the biggest high. I’d been living the deranged life. I felt so nihilistic, yet why hadn’t I just tuned in and dropped out? Instead, I followed Jim Morrison’s credo, the credo of Coleridge and, at one point, Wordsworth, the credo of self-discovery through self-destruction I so willfully subscribed to until this moment:

Live every day as if it’s your last, and one day you’re sure to be right.

On this fateful morning, I’m standing wide-awake at dawn in the living room of my house in Hollywood Hills, overlooking the Los Angeles basin that falls and stretches away toward the high-rising pillars of downtown. I haven’t slept, still buzzing from the night’s booze and illicit substances lingering in my bloodstream, staring at the view of the city beginning its early morning grumblings. Daylight unfolds and casts shadows within the elevation, as if God is slowly revealing his colors for the day from his paint box, the hues of brown and green of earth and foliage offset by the bleached white of the protruding rocks that hold my home in place on the hillside.

Standing at my window, I hear sirens blaring in the distance. Someone wasn’t so lucky, I think as I tune in to the rumble of cars ferrying tired and impatient commuters on the 101 freeway that winds through the Cahuenga Pass, the sound of a world slowly getting back in motion. The constant moan of the freeway echoes that of my tired and played-out soul.

Just the night before, after almost two years of work, we put the aptly titled album Charmed Life to bed. I’m feeling some pressure, home early from the de rigueur studio party. I say that as if we threw one party to celebrate the completion of the album, but the truth is that the party went on for two years. Two years of never-ending booze, broads, and bikes, plus a steady diet of pot, cocaine, ecstasy, smack, opium, quaaludes, and reds. I passed out in so many clubs and woke up in the hospital so many times; there were incidents of returning to consciousness to find I was lying on my back, looking at some uniformly drab, gray hospital ceiling, cursing myself and thinking that I was next in line to die outside an L.A. nightclub or on some cold stone floor, sur- rounded by strangers and paparazzi.

I’ve been taking GHB, a steroid, to help relieve symptoms of the fatigue that has been plaguing me and preventing me from working out and keeping my body in some semblance of good shape. If you take too much GHB, which I’m prone to do, it’s like putting yourself in a temporary coma for three hours; to observers, it appears as if you are gone from this world.

When we began recording in 1988, we promised each other we’d be cool and focused, and not wholly indulge in drugs and debauchery. But as weeks stretched into months, Fridays often finished early with “drop-time”—the moment we all took ecstasy. And then Friday soon became Thursday and so on, until all rules were taboo. We somehow managed to make music through the constant haze. It seemed like every few days I was recovering from yet another wild binge, and it took three days to feel “normal” again. The album proved to be slow going and the only way to feel any kind of relief from the pressure was to get blotto, avoid all human feelings, and reach back into the darkness once again. Somewhere in that darkness, I told myself, there was a secret of the universe or some hidden creative message to be found.

We’d invite girls to come to the studio to listen to the music. Mixing business with pleasure seemed the best way to see if the new songs worked. We’d be snorting lines of cocaine, and then the girls would start dancing. Before long, they’d end up having sex with one or more of us on the studio floor. Once the party was in full swing, we walked around naked but for our biker boots and scarves. Boots and Scarves became the running theme.

The girls loved it and got in on the act. It helped that we recruited them at the local strip bars; they felt comfortable naked. We had full-on orgies in those studios we inhabited for months. It was like a glorified sex club. We were all about instant gratification, lords of the fix.

Now that it’s all said and done, I feel exhausted and shattered. The keyed-up feeling that prevents me from sleeping is the result of the care and concern I put into making a record that will decide the course of my future. That’s the sort of pressure I put on myself every time. Then there’s the fact that the production costs have been astronomi- cal; the need to keep the bandwagon rolling has drained my spirit and sapped my will.

Months later, Charmed Life will go on to sell more than a million copies. The “Cradle of Love” single and video, directed by David Fincher, will both become massive hits. But I don’t know this when I retreat to my home alone at 2 a.m., intending to get some rest after wrapping recording. The breakup of my relationship with my girlfriend, Perri, the mother of my son, Willem, has left me bereft, but finishing the album has been my only priority. “If the thing is pressed . . . Lee will surrender,” Lincoln telegraphed Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox in 1865. And then: “Let the thing be pressed.” That’s a rock ’n’ roll attitude. The difficult has to be faced straight-on and the result forged out of sweat and tears. That’s where I take my inspiration. The wide-screen version of the last few years’ tumultuous events plays in my subconscious and cannot be ignored. What can I do to keep away these blues that rack my thoughts and creep into my bones? It’s a fine day, warming up, the sun burning off the morning smog. Still, I feel uneasy, dissatisfied in the pit of my stomach. With the album now finished, I’ll have to take stock of life and contemplate the emptiness without Perri and Willem.

The bike will blow away these post-album blues, I think. As I open the garage door, the chrome of my 1984 Harley-Davidson Wide Glide gleams with expectation, beckoning me.

The L.A. traffic is thick and the warmth of the sun is fresh on my face, its glow spreading over my bare head. California has yet to pass legislation making the wearing of helmets compulsory, and I’ve always liked the feel of the wind in my hair. My bike clears its throat with a deep, purring growl. The gleaming black tank and chrome fixtures flash in the sharp, sacrosanct daylight. I’ve opted for all denim to match the blue-sky high.

The Harley’s firm hold on the road this morning is comforting, and I begin to relax; its curves perfectly match the contours of the pavement below. I try to outrun the demons. The sweet, jasmine-honeyed air intoxicates my spinning mind. I rev the bike, which reacts easily to my commands as I sail breezily along the winding canyon road toward Sunset Boulevard. The lush greenery and trees lining the road refresh my thoughts, and my concentration wanders. My mind is filled with images of Peter O’Toole as Lawrence of Arabia speeding through the English countryside, testing his bike, pushing it to the limit, when—

WHAM!!!

An almighty explosion interrupts my silent reverie. I feel my body violently tumbling through the air, floating into a pure void. I black out before landing.

I sense beings crowding around me. I hear voices, some very close and loud, others softer and farther away. The whirl of movement in this dark vortex tells me that other worlds exist; I can feel their magnetic pull. People have a gravity of presence, and I can feel their move- ment as I slowly regain my senses. I’m not sure if I’m alive or dead.

I’m transported to just above myself. There are no white tunnels or distant lights, rather a red dimension. Walking through the shadow world on the other side, I see the beings who grace the crimson night crowding around to greet me. They pour out their love. The strange dimension sends a beam of thought: You’re all right. We love you. Don’t worry, here is love. They press and push. The circle of people holds my soul in a warm embrace.

Now I slip into a warp of darkness, pulled from this loving dimen- sion. I hang in a slip of time between life and death; I slowly begin to regain consciousness. The screen behind my eyes has yet to come on. It’s as if God has not yet spoken those immortal words “Let there be light.”

**

I heard the crash. Bikers say that if you don’t hear that crash, you’re already dead. I open my eyes. Bright sunlight floods in. I’m staring at the curb, my forehead resting just an inch from the sidewalk’s edge. I’m lying in a bloody heap in the street, my Harley not too far away.

I’m positioned awkwardly on my left side, on top of my left arm. I free my arm, only to see something is very wrong. My wrist is f-cked up, leaving my fingers contorted, clawlike.

I lift up to look at the rest of my body and a terrific pain courses through my nerve endings. Any attempt at movement brings waves of agony that rack me to the core. Looking down, I see that my right boot is without a heel, smashed into the asphalt. I try to move my leg; nothing happens. I see a bloody, mangled stump sticking through my torn jeans. It looks as if my foot and my lower leg are separated from me, the denim lying flat on the pavement beneath my knee, a pool of blood quickly spreading from the soaked cloth. I lie there and wait for help.

The immortal biker slogan “There are those who have been down and there are those who are going down” reverberates through my brain as I watch a man walk across the street. Though he sees my condition, he asks, “Are you all right?” Ignoring the question, I blurt out, “I’ve got Blue Cross Blue Shield—take me to Cedars-Sinai,” before passing out.

I’m zapped back to reality with a sharp jolt as the EMTs move me from the street to the ambulance on a stretcher. They start to cut my clothes off, and I actually think to myself, Just as well I didn’t wear my favorite leather riding jacket.

The herky-jerky movements of the ambulance as it picks its way through traffic—slowing down then speeding up—combined with the blaring siren are strangely comforting. The actions of the two paramedics are cool, calm, and deliberate. I am in good hands. The speed with which they transfer me to the hospital gurney and take me to the emergency operating room reminds me of an experience I had in Thai land the year before, where I was escorted speedily out of the country by a platoon of the Thai Army, tranquilized and lashed to a military stretcher. By the time I reach the emergency room, the pain is so intense my thoughts are stopped cold as my injuries wreak havoc on my nervous system. I am probably screaming, but I am deaf to any sound.

The fact is, I have been deaf to many things. The road I’ve taken may have been the one less traveled, but definitely not in a good way. It was littered with disregarded warning signs. Despite spiritual reassurance by those friendly beings regarding my mortality, back in the real world, it’s payback time. It is not the first time nor the last that William Broad will be held to account and asked to pay a heavy price.

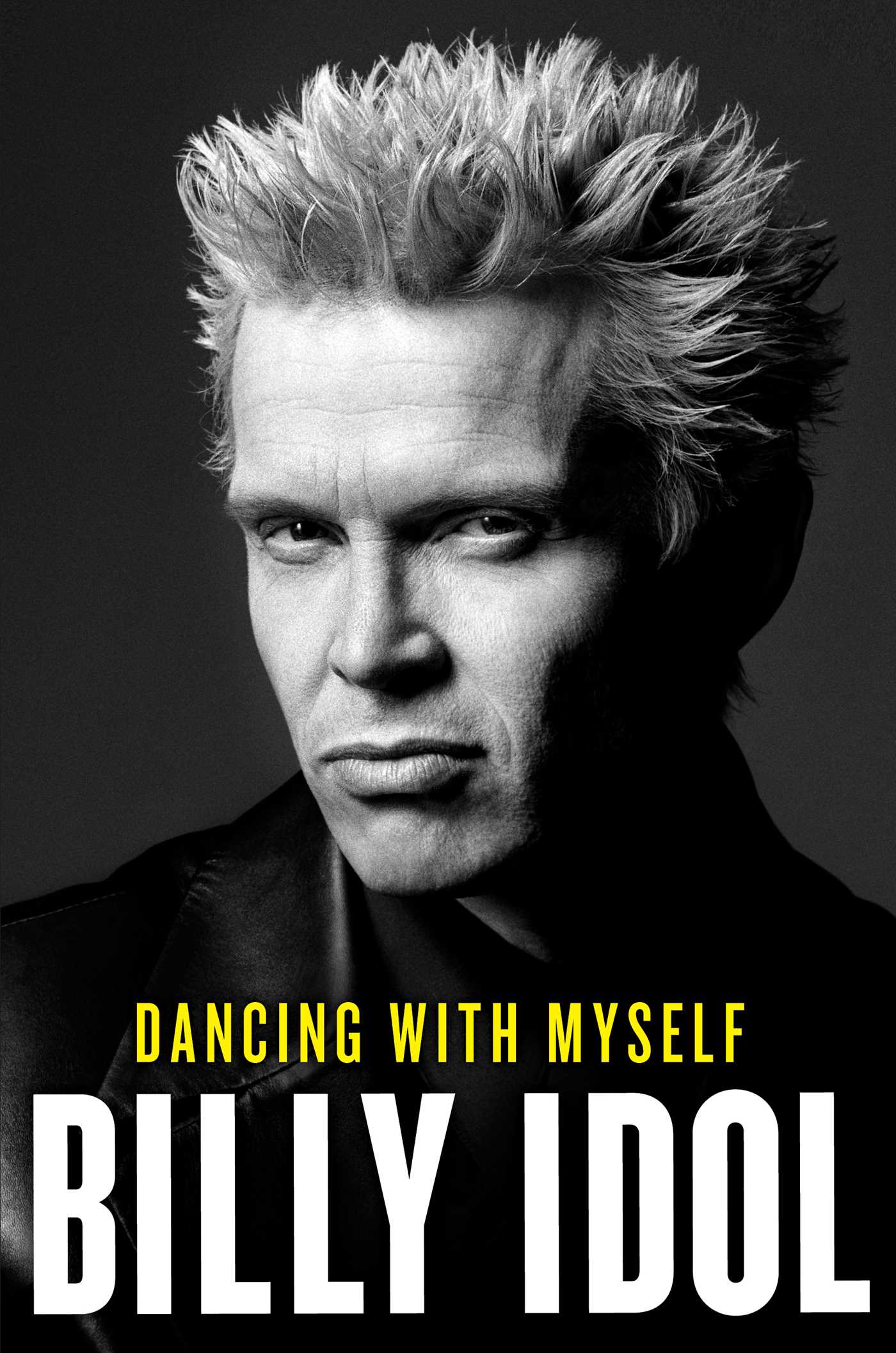

From DANCING WITH MYSELF, by Billy Idol. Copyright © 2014 by Billy Idol. Published Touchstone, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Reprinted by permission.

Billy Idol is a multi-platinum recording artist and Grammy nominee, and has written songs such as “White Wedding,” “Rebel Yell,” and “Cradle of Love.” He lives in Los Angeles.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- What Student Photojournalists Saw at the Campus Protests

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Scientists Are Finding Out Just How Toxic Your Stuff Is

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com