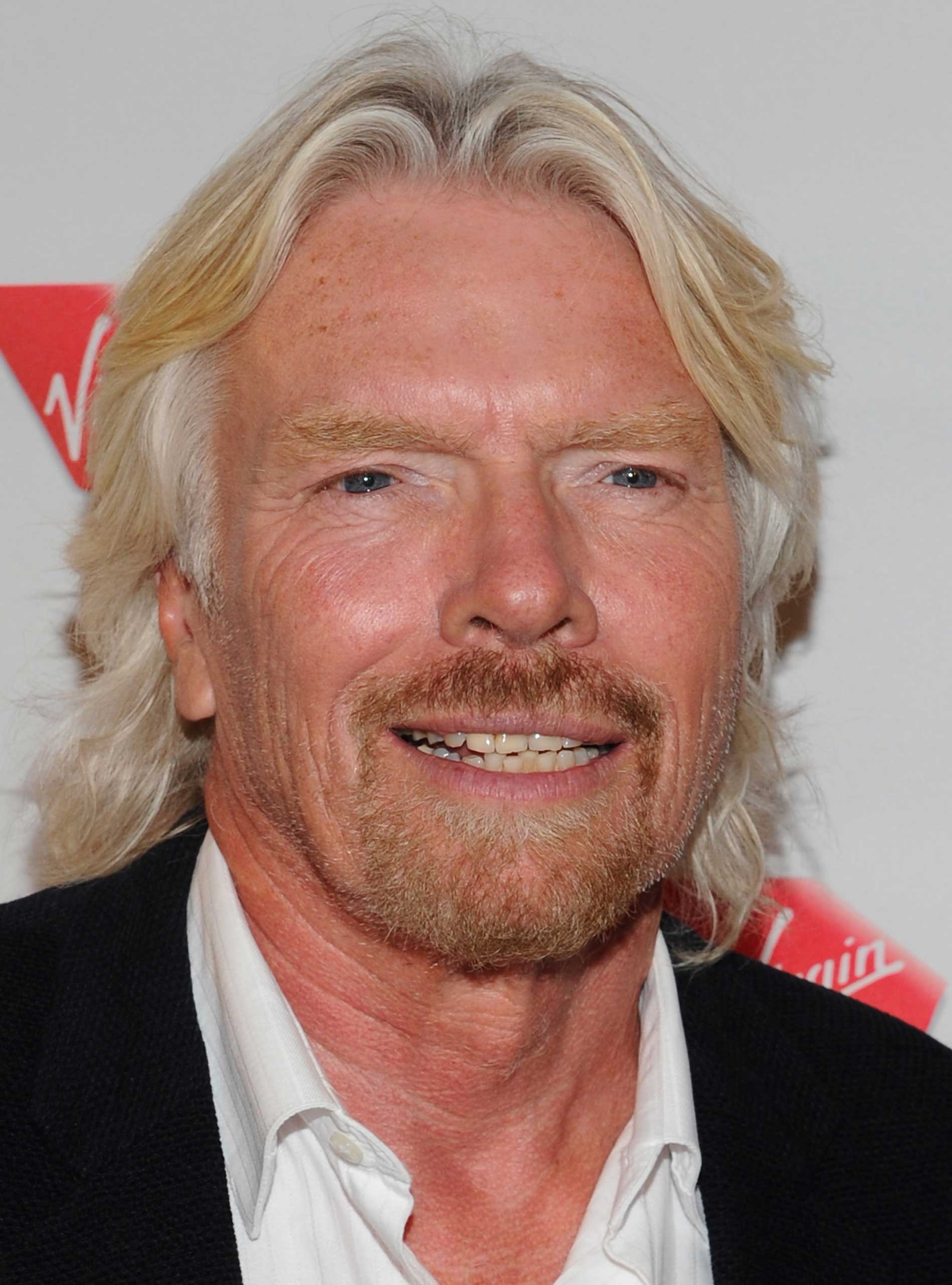

He is more than a business pioneer—he’s an entrepreneurial guru and a leadership rock star. Searching the web for articles by or about Sir Richard Branson, we quickly noticed something: writers gush about him. Branson, in turn, gushes about innovation and the people who work for him. Lots and lots of gushing.

It’s easy to see why. People matter to Branson. He openly uses the word “love” when referring to his employees. He talks about respect for them and how he wants them to feel wanted and cared for. And he credits them for much of his astounding business success. He once won a lawsuit against a competitor and split the $500,000 award with his workforce.

So his latest announcement, giving his employees unlimited vacation time, fits with his benevolent philosophy of leadership and business success. And it has stirred up a lot of gushing for its boldness and the trust it expresses for employees.

We remain skeptical.

At first glance, Sir Richard seems to fit the mold of what we refer to as pragmatic benevolence. Benevolent leaders care about and listen to their employees. They recognize that talent and passion drive results, and that happy workers are more creative and engaged. And such leaders know that fostering debate and candor is a much better way to reveal creative ideas and innovative solutions than to lead from the top down. That is why benevolent leaders listen carefully to subordinates. Or as Branson puts it, “It’s so important to be a good listener. And so many people, they think they know it all and they like hearing their own voice, but being a good listener, you can get so many other ideas from other people to work out whether your idea is a good one or not.”

But look closer and it is not so clear that the no-limits vacation policy benefits the people he claims to love so dearly. What is clear is that so-called “endless summer” vacation policies benefit the companies that implement them.

First of all, they are good for the bottom line. By giving employees unlimited vacation time, instead of giving a set number, say 14 or 21, companies do not have to pay departing workers for unused days. That is a lot of money a company does not have to keep in the bank or on the books.

Second, companies can highlight the policy in their recruiting efforts. Imagine a young (and relatively inexpensive) college graduate offered a job with Netflix or Virgin Mobile and told he can take as much vacation time as he wants, as long as he gets his work done. Sounds like college itself. Show me where to sign, dude!

And third, if your main job is to draw attention to the Virgin Group (of which Branson is not its CEO or chairman, but rather listed only as founder), then announcing a no-limits vacation policy is destined to get the pundits gushing as usual. Free press. Practically free advertising.

And if we look at it from the perspective of the beloved employees, unlimited vacation time is anything but unlimited. With one of the least generous vacation policy cultures in the industrialized world (only South Korean workers earn fewer vacation days), U.S. workers work more hours and later into life than in decades prior, and more so than workers in similar societies. More than a quarter of “guaranteed” vacation days go unused in the U.S. The two most vacation-deprived countries in the world are the U.S. and Japan.

So is it really true that if you treat employees like adults, show them trust, and let them use their own judgment they will get more rest and be more productive?

Nope.

Hiring highly motivated and responsible people of course makes sense. But the same attributes that Branson looks for in his employees makes them less likely to take vacation time. All organizations have a combination of internal cooperation and competition. On the cooperation side, nearly all work in this modern age is accomplished by teams. People tend to feel loyal to their team members. When you take vacation time, who does your work while you are away? Your team! That is one reason people do not use their “guaranteed” paid time off. On the competition side, not everyone can get promoted at the same time, so management watches and evaluates each individual against others to determine who gets the raise, the promotion, or the place on the cool new project team. Are you sure you want to take that last week of the quarter off to travel with your family?

And then there are the jobs that depend on day-to-day routine processing, rather than project work that comes to completion just in time for vacation (or not). If you have a job processing receivables, or maintaining equipment on a daily basis, or monitoring and responding to customer complaints, or working the helpdesk, or keeping up with social media, your absence, however limited, puts your work on your colleague’s desk. On a team of three, you just upped your buddy’s workload by half. How many days will you be gone?

Finally, this new policy (or “policy-that-isn’t,” as Branson puts it) is highly ambiguous, and most people are reassured by a reasonable degree of structure. Tell someone she has exactly 21 days to use for vacation per year, and she has to use them without checking her email and that she does not have to worry about any problems while she is gone, and her mind will be more at rest than if you tell her to take all the time off she wants as long as she maintains the same level of performance and responsibility she would if she were in the office.

In many of the situations above, even if you take a vacation, you will probably dial in remotely to stay up on some work, or respond to at least a few of the hundreds of emails otherwise waiting for you on that first Monday back.

So we ask Sir Richard: Is this anything more than another stunt? One answer can be inferred from the original announcement he made in his blog:

. . . simply stated, the policy-that-isn’t permits all salaried staff to take off whenever they want for as long as they want. There is no need to ask for prior approval and neither the employees themselves nor their managers are asked or expected to keep track of their days away from the office. It is left to the employee alone to decide if and when he or she feels like taking a few hours, a day, a week or a month off, the assumption being that they are only going to do it when they feel a hundred per cent comfortable that they and their team are up to date on every project and that their absence will not in any way damage the business – or, for that matter, their careers!

Okay, now review those last two words about what he is warning people to be sure not to damage. Now ask yourself if you have ever been 100% comfortable about your career while working for a large corporation. Obviously someone is keeping track of something or this would not qualify as an organization. He is giving every salaried worker the opportunity to outperform colleagues. He is potentially undercutting cooperation, and probably adding to the stress of his employees. And he is even making it acceptable to take no time off.

“Oh, please!” you might say. “That is such a cynical interpretation of such a wonderful and visionary policy.”

So ask yourself this: Did he listen to his employees? We know he listened to his daughter, because the Daily Mail reported it, but nowhere is it reported that he involved his employees in the decision.

Truly benevolent leaders, partly out of real caring and partly out of pragmatism, want their subordinates to honestly weigh in on many big questions, especially those that will affect motivation and well-being. Did he say to his employees, “What vacation policy is best for you and the company?” The new policy only affects his staff of less than 200 people. But he says if it is successful he will encourage other companies in the Virgin Group to offer the policy to more of its 50,000 employees worldwide. How much will he involve those employees in this next big decision?

Will he ask for ideas and opinions from several hundred employees? Or several thousand? Will he encourage an internal research team to review the most effective vacation policies across industries? Will he hold focus groups? Will he make it clear that asking him tough questions or disagreeing with him or offering other ideas that he might not have considered or may not even feel comfortable with is not only okay but rewarded? Will he openly acknowledge that different people are motivated by different policies, and ask how can we offer unlimited vacation to some employees while others get a set amount of days that they have to take off without any negative consequences because the management structure will make sure the workaholics do not get rewarded more than involved fathers and mothers?

Such a process of employee discussion inevitably involves constructive, passionate debate and tense but healthy conflict. And yet there could be huge payoffs before his next big announcement. Such a pragmatic and benevolent process will most likely result in a policy or combination of policies that make for a more motivated and satisfied workforce, and a lot of people going home to tell their families, “the boss really cares about my opinion, and about us.”

But that would not produce much gushing in the press.

Peter T. Coleman is a professor of psychology and education at Teachers College and the Earth Institute at Columbia University and director of Columbia’s International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution. He’s also a consultant and New York State certified mediator whose clients include IBM, Citibank, and the UN.

Robert Ferguson is a psychologist, executive coach, and management consultant who has provided consulting and training to organizations including Credit Suisse (USA), Merrill Lynch, and Aegon.

Their book, Making Conflict Work: Harnessing the Power of Disagreement, is out this week.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com