Correction appended: Sept. 29, 2014, 9:50 a.m. E.T.

For a region of only about 400 square miles, Hong Kong has seen more than its share of protest in the last century. The uprising that sprang into action this week — as “Occupy Central” protesters demand the ability to elect their next local government head, the Chief Executive, without the intervention of Beijing — is part of a long history of political conflict in the area.

1967: Communists in the British colony of Hong Kong rise in support of the Cultural Revolution sweeping China

When England took control of Hong Kong in 1842 after the first Opium War, British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston is said to have remarked that it was “a barren island with hardly a house upon it” — but by the middle of the 20th century Hong Kong was becoming a prosperous business center. The cultural difference between the Communist mainland and the neighboring region was thrown into stark contrast in 1967.

Though the initial protests of that summer seemed to have arisen organically among Hong Kong workers, China supported the movement from afar and issued an ultimatum demanding that arrested protesters be freed; the ultimatum, however, did not involve any question of British control of the area. As TIME explained, the situation between the two nations was one of “mutual dependence”:

Britain wants to hold onto Hong Kong to protect its vast investments and to retain a Far Eastern headquarters for British banking and trade interests. It also does not know how it could gracefully withdraw from Hong Kong under the present circumstances without totally losing face in the Orient. In recent years, Red China has been building up its influence in the Crown Colony, and Britain has been too afraid of offending its overpowering neighbor to do anything about it. As a result, about one-fifth of the colony’s Chinese, who make up 99% of the 4,000,000 population, are openly pro-Peking, and the rest play it safe. Red China commands the support of three of Hong Kong’s major daily newspapers, the most important labor unions, and a large number of schoolteachers, which is one reason a high proportion of young Chinese in Hong Kong are Maoists.

That July, when shots from across the Chinese border killed five Hong Kong police officers, the U.K. responded by sending in troops, the first armed confrontation between British and Chinese soldiers in Hong Kong since Communist rule had begun in China nearly two decades before. Though the stand-off between the two powers could have gotten even more intense, by early August things had calmed down.

And that bitter history did not keep China and Hong Kong from getting closer in the decade that followed. Rather, they grew to rely on one another, economically at least: TIME reported in 1979 that China sent an annual $2 billion in exports to Hong Kong, while the same amount went back to the mainland in remittances from residents and earnings of Chinese companies located there. Hong Kong businesses relied on Chinese labor, while the Chinese government used Hong Kong as an outlet for its economic dealings with the rest of the world.

1989: Tiananmen Square helps Hong Kong’s independent political identity take shape

Economic interdependence was a major factor in shaping the 1984 decision about what Hong Kong would look after the U.K. handed over control in 1997. According to the agreement, the preexisting “system of law” and capitalist economy would be preserved even as the region became part of China. The decade-long period of transition, however, was marked by more strife.

In 1989, as pro-democracy protests gripped the mainland, a full one-sixth of Hong Kong’s population (by TIME’s count) came out to march in support of that cause. Meanwhile, many in Hong Kong weren’t much happier with the U.K. than they were with China: even as it began to seem that Beijing’s grasp on Hong Kong might be tighter than expected, Westminster also made it harder for residents of the colony to settle in the U.K., a move that left many Hong Kong residents feeling stranded between two cultures. After the Tiananmen Square massacre that summer, the modern Hongkonger identity began to crystallize. According to TIME’s reporter in Hong Kong at the time, Hong Kong residents were both firmly pro-democracy and firmly Chinese:

The glittering glass-and-steel Bank of China, Southeast Asia’s tallest building and a prominent addition to Hong Kong’s spectacular skyline, was to embody the faith that both Hong Kong and China placed in a common future, a visible symbol of the ”one country, two systems” promised when the British crown colony reverts to China in 1997. Last week two enormous black-and-white banners drooped across the tower’s facade bearing a grim message in Chinese characters: BLOOD MUST BE PAID WITH BLOOD.

Overnight the savage massacre in Tiananmen Square shattered Hong Kong’s wary faith in that future. Thousands donned funeral garb to mourn the dead of Beijing. The stock market plunged 22% in one day in a paroxysm of lost confidence. Chinese flocked to mainland banks to withdraw their money, as much in anger as in fear. And the largely apolitical people of this freewheeling monument to commercialism discovered a newfound political activism.

The grief and fury felt in Hong Kong are the latest expression of a startling change in the colony’s view of itself. Throughout its almost 150-year history as a bold, pushy trading enclave, the business of Hong Kong has been business. The colony was a place where foreigners and Chinese alike came to make money and get away from the political turmoil on the mainland. But since the student movement blossomed in Beijing last April, Hong Kong has been galvanized. It has found an identity at last, and it is Chinese.

2003: Pro-democracy protests return

In the early ’90s, Hong Kong Governor Chris Patten — the last British governor of the region — proposed a plan to further democratize Hong Kong’s government, over Beijing’s objections. So when the transfer took place in 1997, the question of how much democracy would last, and for how long, lurked beneath the smoothness of the hand-over.

Less than a decade later, that concern proved well-founded: in 2003, Hong Kong residents took part in what was the biggest pro-democracy protest in the whole country since 1989, sparked by a new antisubversion national security law, which ended up not passing. As TIME noted, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive had been counted on to “keep Hong Kong in its place,” but it was becoming clear that such a task was easier said than done.

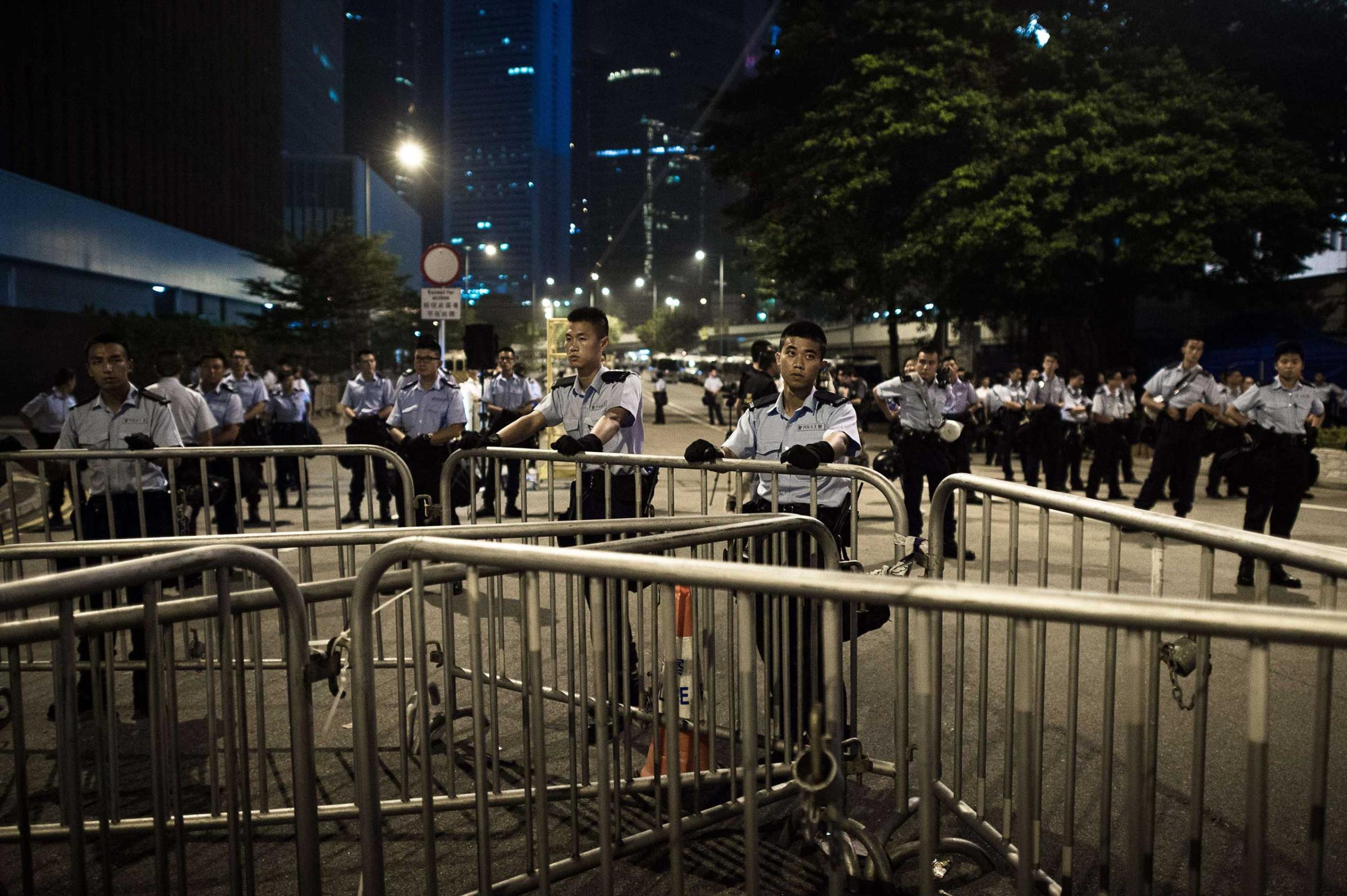

2014: “Occupy Central” begins

Read more about the ongoing protests in Hong Kong here, on TIME.com: Hong Kong’s Protesters are Fighting for Their Economic Future

Photographs of Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution

Read TIME’s 1989 cover story about the Tiananmen Square massacre, free of charge, here in TIME’s archives: Despair and Death In a Beijing Square

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the year in which England took control of Hong Kong. It is 1842, not 1942.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com