Despite their wholesome, all-American reputation, Charlie Brown and his friends embody an amount of malaise better associated with French existentialists. Over nearly 50 years and more than 18,000 comic strips, Peanuts made punchlines out of loss and futility. The joke was on humanity. And it started right away: creator Charles Schulz relied on themes like unrequited love and the cruelty of children as early as the comic’s newspaper debut on this day, Oct. 2, in 1950. The very first strip shows Charlie Brown walking by two children, one of whom declares, over four panels: “Well! Here comes ol’ Charlie Brown!/ Good ol’ Charlie Brown… Yes, sir!/ Good ol’ Charlie Brown…/ How I hate him!”

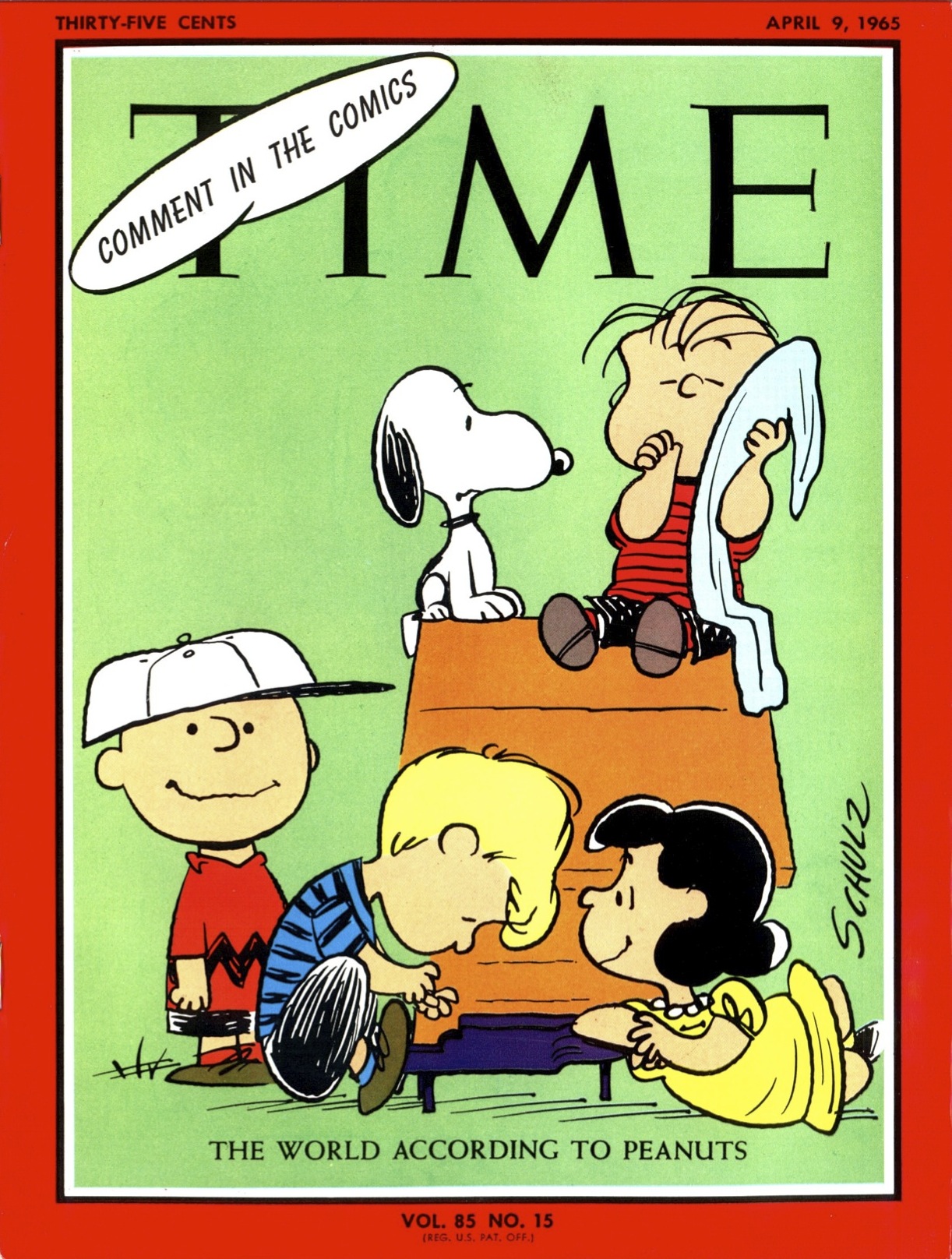

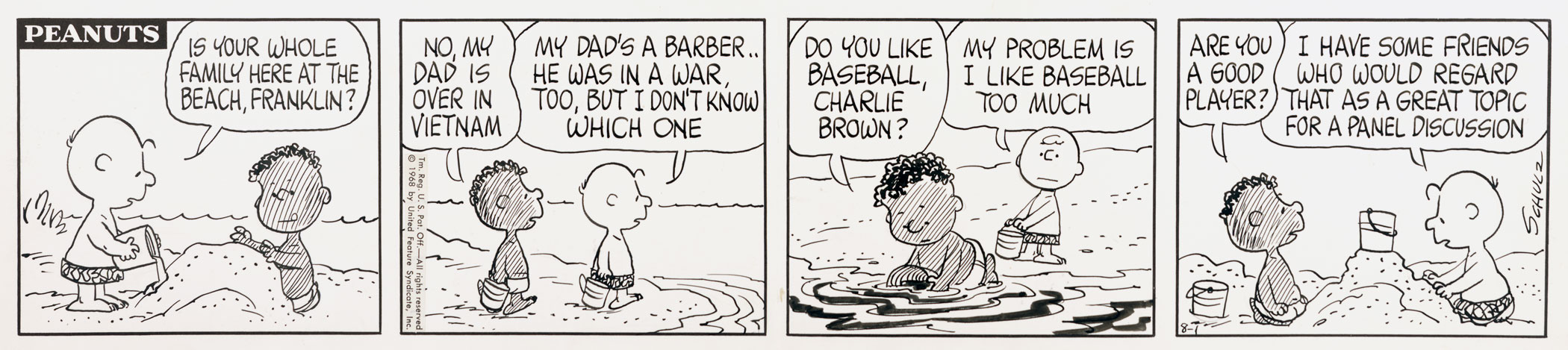

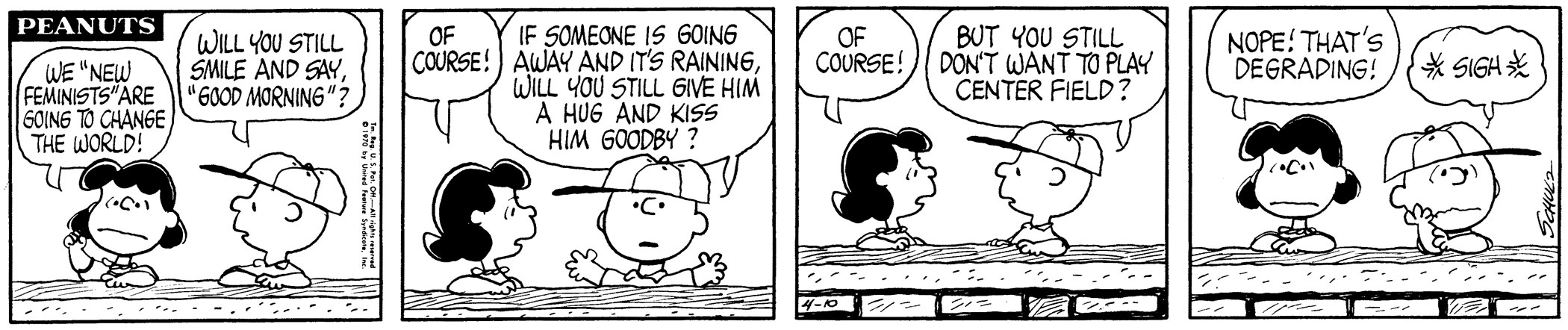

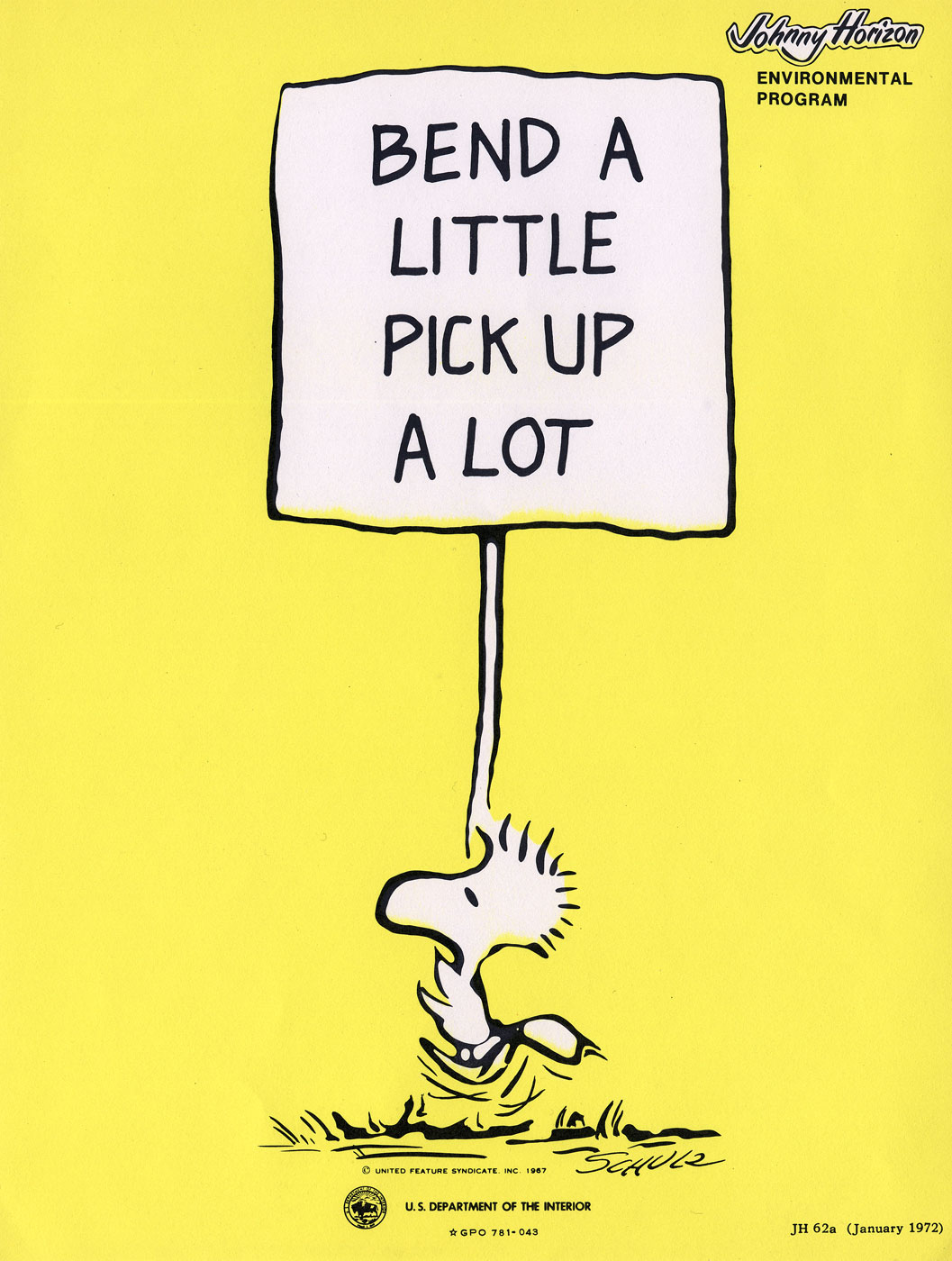

That combination of wit, pathos and social commentary was why TIME put Peanuts on the cover in 1965, and why the power of the strip persists to this day, as evidenced by plans for a 2015 Peanuts movie, complete with 3D computer graphics, and the fact that the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, Calif., is currently hosting an exhibit about the way the strip addresses still-relevant social issues.

“Most of us will lose more often than we win. That’s the joke of Peanuts,” TIME’s James Poniewozik wrote in 1999, when Schulz announced that he would quit writing the comic. “Schulz made it funny with characters who faced a Sisyphean suburban world of kite-eating trees and yanked-away footballs with resilience and curiosity.”

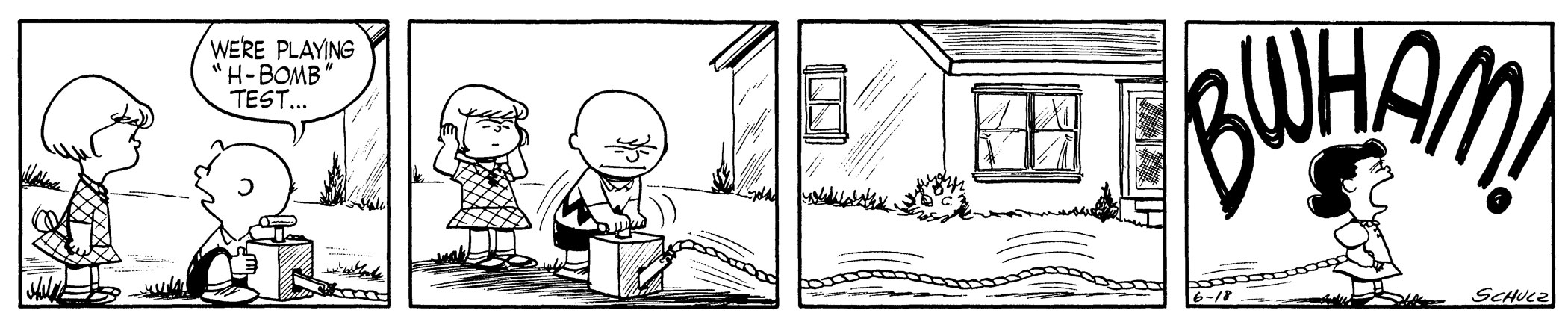

Schulz, who struggled with depression and anxiety, poked fun at his own challenges by exaggerating them in his main character. (One example that Poniewozik cites: “On Tuesdays I worry about personality problems,” Charlie Brown commented in a 1960 strip. “Thursday is my day for worrying about the world getting blown up.”)

And Schulz drew on real-world friends and relations to populate the strip with its quirky characters. One, the Little Red-Haired Girl, for whom Charlie Brown pines but to whom he is invisible, was based on a former co-worker who had rejected Schulz’s marriage proposal. In his biography, Good Grief: The Story of Charles M. Schulz, he acknowledged that he had never gotten over his disappointment.

The humor of Peanuts lies in the extremity of bad luck the characters — particularly Charlie Brown — endure. Schulz’ obituary in the New York Times pointed out that Charlie Brown “once held onto the string of a kite that was stuck in a tree for eight days running, until the rain made him stop.” The obituary, reporting Schulz’s death from colon cancer the day before his final Sunday comic strip was published in 2000, goes on to quote Schulz’s summary of his formula: “All the loves in the strip are unrequited; all the baseball games are lost; all the test scores are D-minuses; the Great Pumpkin never comes; and the football is always pulled away.”

But Charlie Brown persevered nonetheless, and Schulz kept writing. More than 350 million readers joined him in laughing at life’s cruel absurdities. “You can’t create humor out of happiness,” he wrote in his 1980 book, Charlie Brown, Snoopy and Me. “I’m astonished at the number of people who write to me saying, ‘Why can’t you create happy stories for us? Why does Charlie Brown always have to lose? Why can’t you let him kick the football?’ Well, there is nothing funny about the person who gets to kick the football.”

Read a 2000 remembrance of Charles Schulz, here in TIME’s archives: The Life and Times of Charles Schulz

See How Peanuts Addressed Feminism, Nuclear War and More

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com