Two years before the Korean peninsula erupted in a civil war that saw the North and the South (and the U.S., the United Nations, the Soviet Union and China) engage in a conflict that shaped the post-World War II world, a short, brutal rebellion in the young Korean republic paved the way for the cataclysmic Korean War to come. The Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion, as it came to be called, took place in October 1948, when communist rebels — many of whom had been in the American-trained Korean Army — revolted against the (authoritarian) government of President Syngman Rhee.

As tensions on the peninsula again reach a boiling point and as the rhetoric from both sides — especially from the North’s young, largely untested leader, Kim Jong Un — grows more belligerent and more bizarre, the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion might seem like little more than a historical anomaly: a minor, forgettable blip in Asia’s long, fraught history.

But in cultures that measure their histories in terms of millennia, rather than decades or even centuries, a revolt and its repression is not merely remembered seven decades later; instead, it helps inform every utterance, every threat, every gesture emanating from South Korea and North Korea today.

Here, in an effort to perhaps add some needed context to the current situation on either side of the 38th parallel, LIFE.com presents a series of photos by the great Carl Mydans, who was on the ground when the rebellion began, and bore witness to the carnage that followed. Most of these pictures never ran in LIFE magazine. (We should also note that the Yeosu-Suncheon Rebellion came on the heels of the South Korean army’s notoriously violent suppression of an uprising on the island of Jeju, off the southern coast of Korea, in April 1948.)

[See all of TIME.com’s Korea coverage.]

In November 1948, in an article titled, “A New Communist Uprising Turns Men Into Butchers,” LIFE painted an unsettling picture of the rebellion, complete with the observation that the United States “gave South Korea a government” after the Second World War — suggesting, unintentionally perhaps, that the Korean peninsula was once again little more than a convenient crossroads upon which more powerful nations have always fought their proxy wars.

Sooner or later the cold war in Korea was sure to turn hot, and so it did in late October on a signal from the Soviets. The reasons were well known: Korea had been split between U.S. and Soviet control at Yalta, and the Soviets obstructed all later efforts to unite it, preferring to establish a Communist “people’s republic” in North Korea and equip it for civil war which would make all Korea Red. The urgency increased in August when the U.S. gave South Korea a government under President Syngman Rhee. When the Red rebellion came, it splattered blood across the new southern nation.

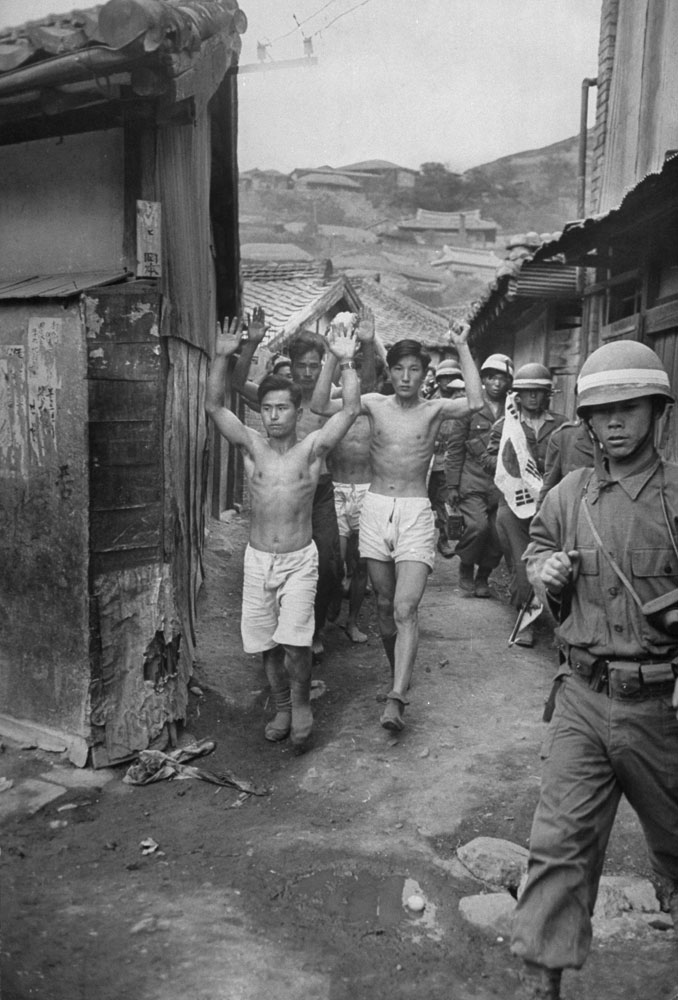

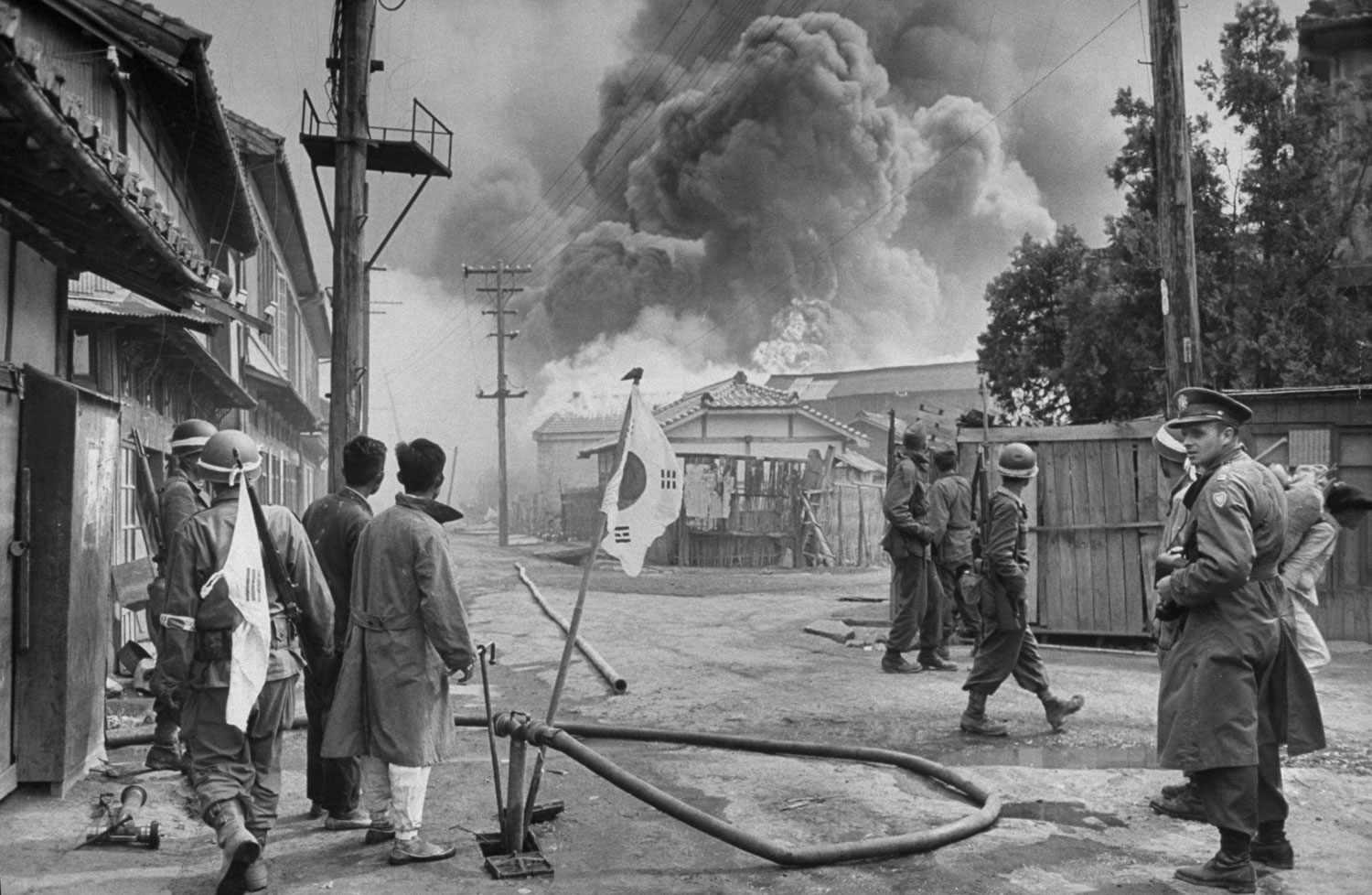

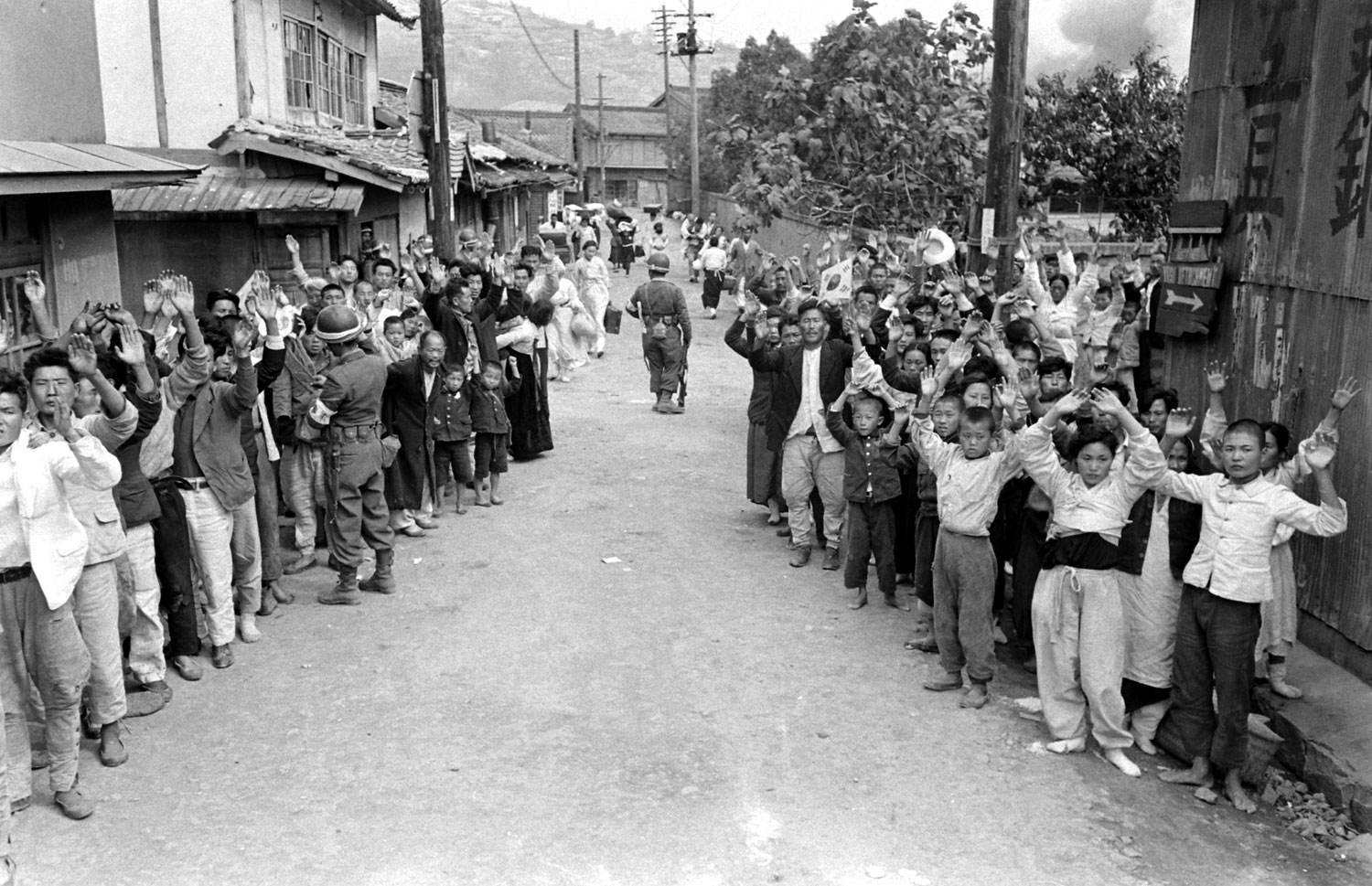

It began on the cool night of Oct. 19 while the Moscow radio trumpeted the news that Soviet troops were leaving Korea. Simultaneously a Red cell of 40 soldiers in a regiment of the American-trained Korean national army at the southern port of Yosu [today spelled “Yeosu”] killed the regimental officers, gathered the entire regiment in revolt, murdered the local police and quickly captured both Yosu and the city of Sunchon 25 miles to the north. There the rebels, still in American Army uniforms, and followers raised the flag of the North Korean People’s Republic, and for a few bloody days ruled a small chunk of Rhee’s south. Before they melted into the hills, at least temporarily repulsed by loyal troops, LIFE’s Carl Mydans was on the scene with a camera to record the brutal consequences.

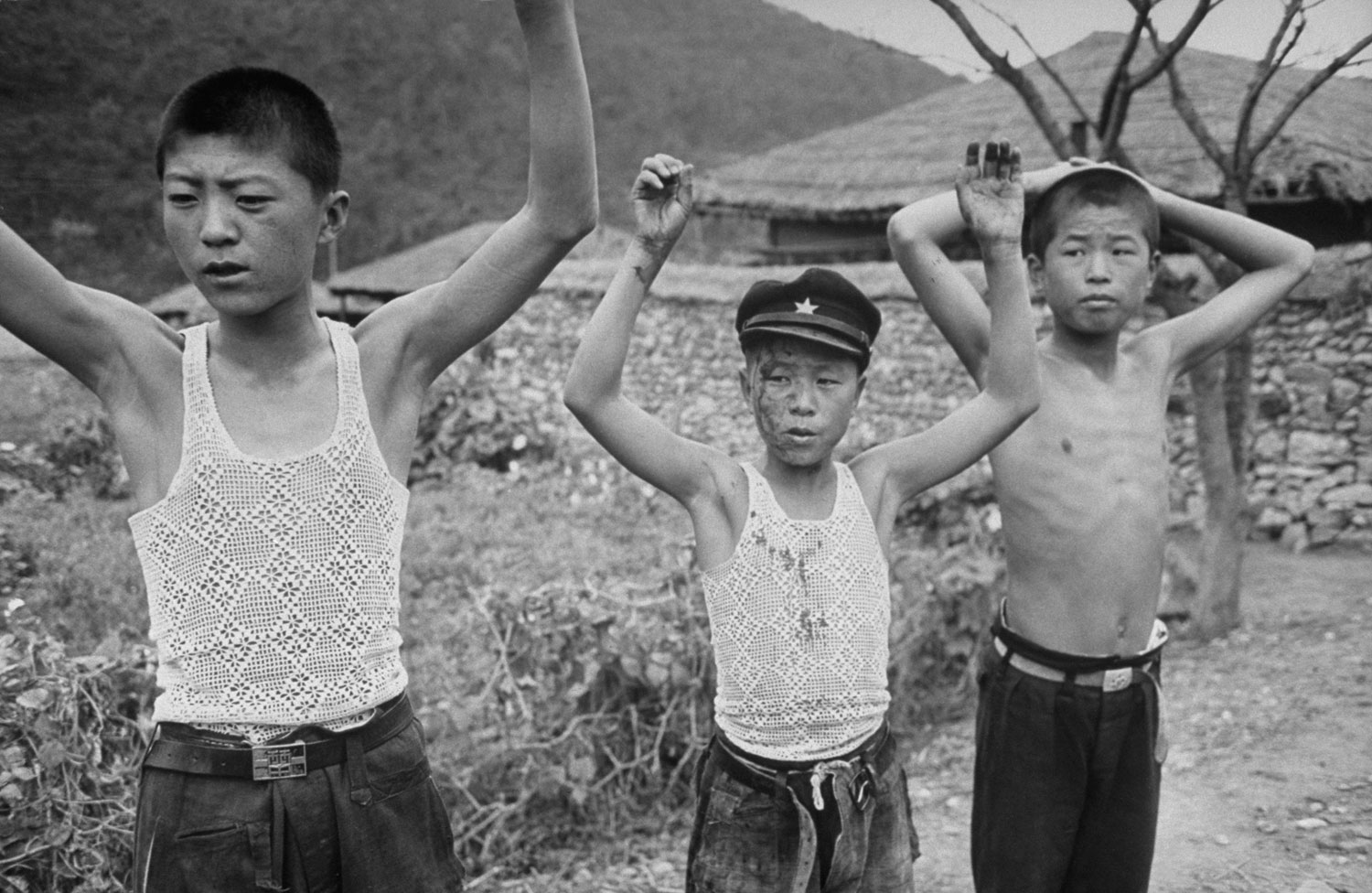

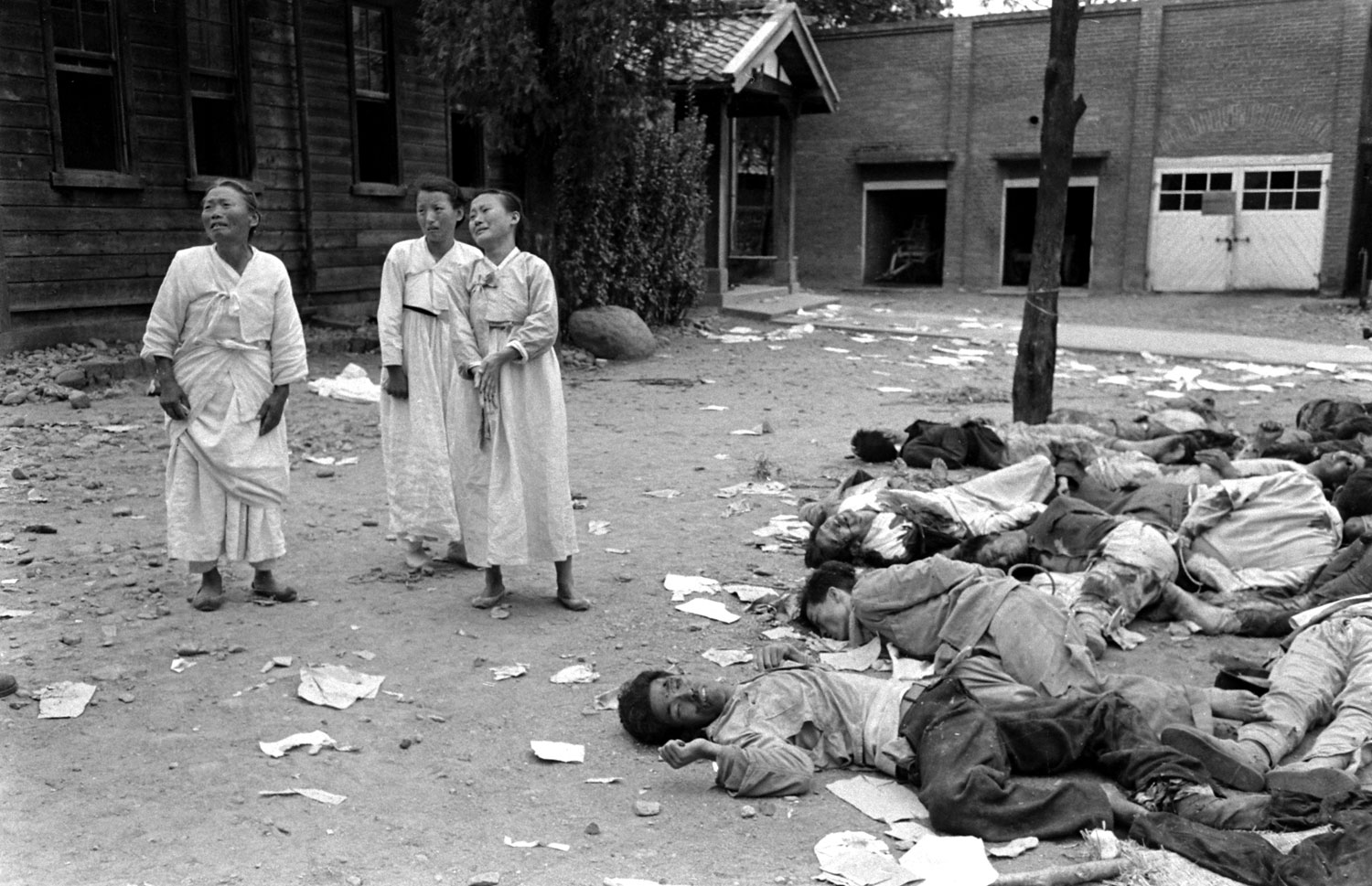

At Sunchon [today spelled “Suncheon”], which means “Peaceful Heaven,” the rebellion’s Red leaders opened the city jail and let political prisoners lead them through the city from house to house pointing out enemies for revenge. With this help the rebels had slaughtered about 500 civilians and 100 police before the Korean national army retook Sunchon (pop. 60,000) on Oct. 23. Then it was the government’s turn, and LIFE’ Carl Mydans watched with horror as the process of retribution began. [This is what he] cabled:

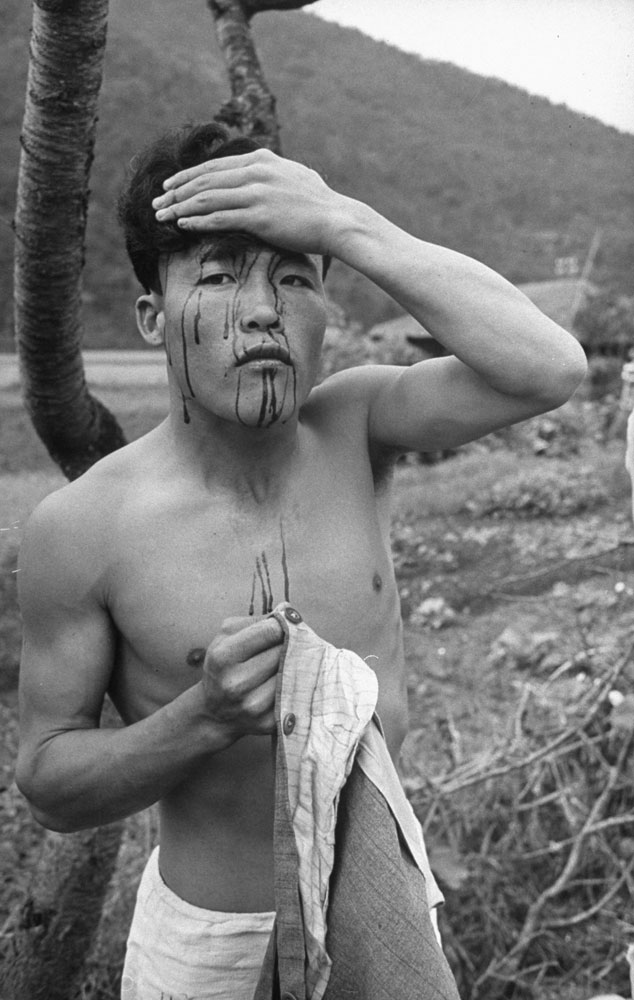

“Now the national army, aided by a few police who had fled to the hills and come back, repaid brutality with brutality. We watched from the sidelines of a huge playground with the women and children of Sunchon while all of their men and boys were screened for loyalty. Four young men stripped to their shorts were on their knees begging. One had his hands up in a symbol of prayer. Suddenly these suppliant hands were crushed into his mouth and nose as a rifle but smashed his teeth. Behind them stood men with clubs . . . who beat the kneeling group until the beaters, grinning, had to pause for breath. . . .

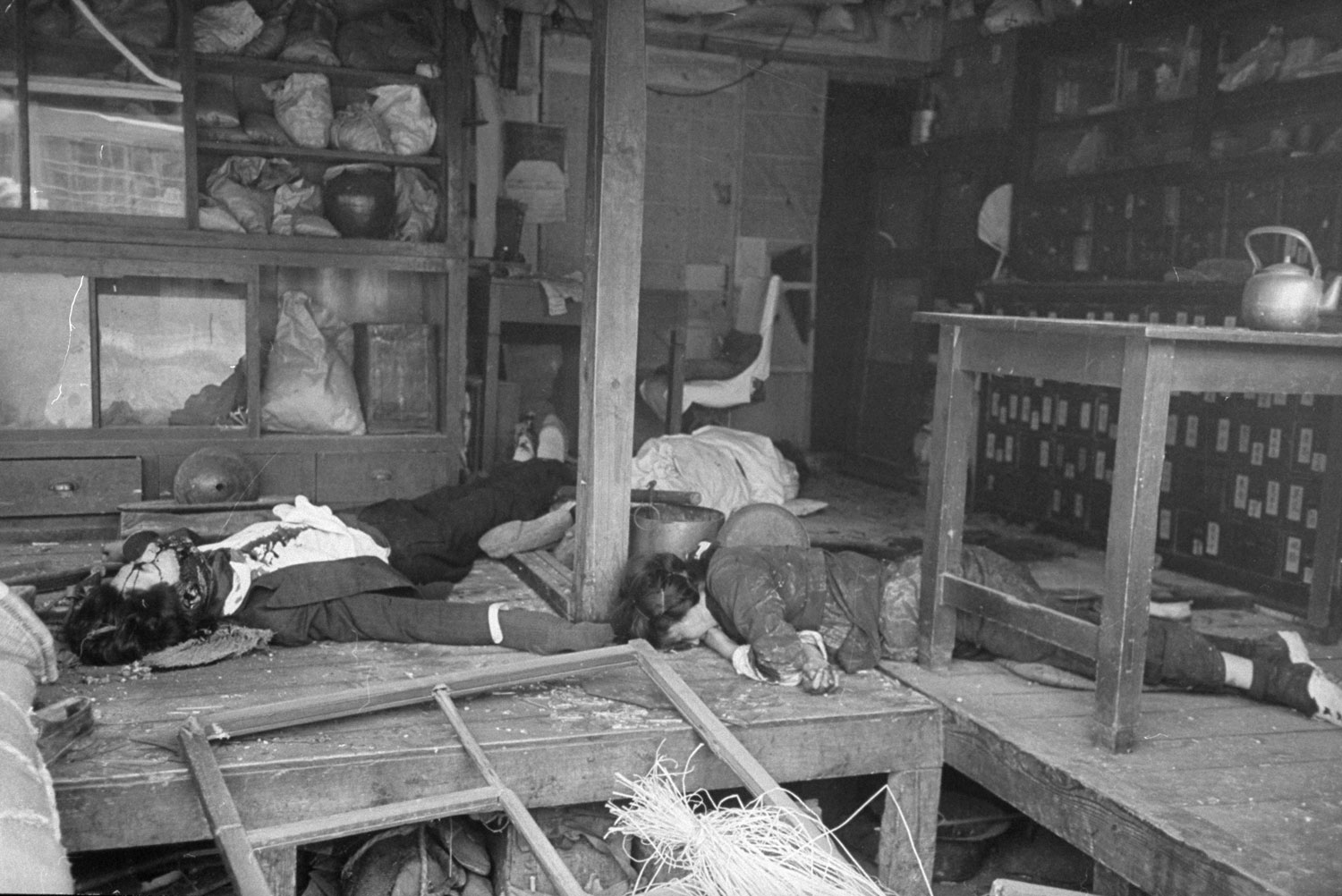

“We drove through the city — empty except for bodies — and here we saw the reason for the brutal retaliation. Bodies lay just as they had been slain by the rebels — in heaps with hands tied behind their backs. . . . Some were burned in charred masses on the streets, or lay alone where they had fallen beside looted shops and homes.

“Later, when it was safe, women streamed away from the big playground to poke among the heaps of bloated dead — a scene not easy to watch. When they found theirs, they were stoical at first. Then tears came and they were hysterical.”

In type-written notes sent to LIFE’s editors on October 24, 1948, Mydans was even more plainspoken about the terrors he and three other correspondents (see the photo above) witnessed during the rebellion and its suppression. “Covering this war is difficult and frightening,” he wrote. “Both factions in the fight wear the same uniform, ride in the same American vehicles and are armed with the same weapons. . . . Tonight as I write this in the hillside home of [Presbyterian missionary] Dr. Crane the reports of rifles and automatic weapons still sound nearby and to we four correspondents it carries the full feeling of war.”

“We entered Sunchon 1 PM on the 24th,” he continued. “The city stank of death and was ill with the marks of horror.”

Almost plaintively — but with never a hint of self-pity or complaint — Mydans also noted that “it is now midnight and we haven’t been to bed for two days. . . . We [he and the three other newsmen] are all the outside observers there are of this point in Korean history.”

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com