The horrifying events of the past weeks in Syria and Iraq have significantly shifted the terms of the debate about whether intervention is desirable or sensible to counter the violence in the Middle East and its potential impact back in our own countries.

President Obama is rightly building the broadest possible coalition for action against ISIS and should be given all support necessary. It is also clear that he is developing US strategy in a way that recognises that the threat is bigger and broader than ISIS. This is important and should also be supported. Secretary John Kerry has succeeded in putting together a formidable array of allies for the immediate task; France has already taken action; David Cameron is pledging British support. Today’s leaders have this opportunity: as a result of changes in the politics of the Middle East, there is a real possibility of building a coalition that goes far beyond the West. Leading Arab nations are also part of the coalition. This is invaluable and corrects one of the principal weaknesses of Western strategy after September 11th 2001.

In addition, there are at least the beginnings of an emerging consensus which is global, about the nature of the threat we face. It is clear that there is a fundamental problem with radical Islamism; clear that it is deep; clear that the solutions are not easy or presently to hand; clear that this is the work of a generation not an election cycle; and clear – most important of all – that this is ‘our’ challenge and not simply ‘theirs’.

Without a comprehensive strategy, we will face a future marked by conflict and instability across swathes of the world and major acts of terrorism in our own lands.

However there is still hesitation and unresolved expanses of discord in how we describe the problem and therefore in how we confront it. Here I will set out my analysis of what has happened, what is happening and what will happen and my belief that without a comprehensive strategy, we will face a future marked by conflict and instability across swathes of the world and major acts of terrorism in our own lands.

By all means let us take strong action against ISIS and against the citizens of our own country that seek to join them. But action against ISIS alone will not suffice. We need to recognise the global nature of the problem, the scale of it, and from that analysis contrive the set of policies that will resolve it. I want to set out seven principles of understanding that I believe should underpin such a strategy.

Islamism of course is not the same as Islam. The religion of Islam is an Abrahamic religion of compassion and mercy. For centuries it shamed Christendom with its advances in science and social development. This is not a clash of civilisations. It is a struggle between those who believe in peaceful co-existence for people of all faiths and none; and extremists who would use religion wrongly as a source of violence and conflict. Our enemies are those who would pervert Islam. Our allies are the many Muslims the world over who are the principal victims of such a perversion.

I also completely accept that strains of extremism are not limited to the faith of Islam. Such strains exist in most faiths. But not on this scale or with this effect. I agree too that in times past, Christianity exhibited cruelty and engaged in persecution that produced war and suffering. How Christianity escaped from that madness, is its own story. But we’re dealing with the present.

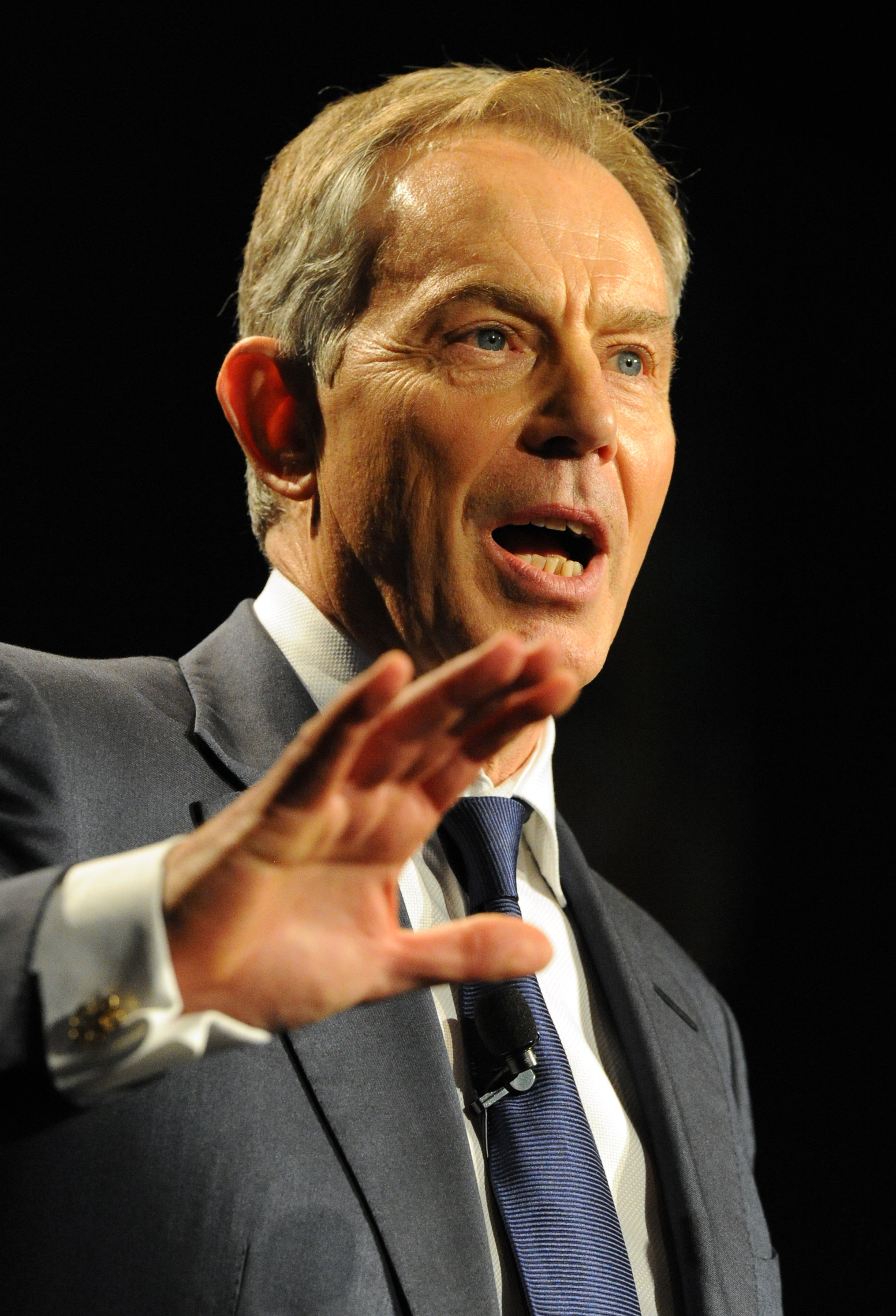

The views I put forward are of course in part shaped by my experience dealing with this issue as Prime Minister after the terror attack, planned from the training camps of Afghanistan, of September 11th 2001, in which over 3000 innocent people lost their lives on the streets of New York and elsewhere; and the terror attacks in Britain of 7 July 2005 by British born Muslims. But they’re equally the product of the last 7 years spent outside official office, in the Middle East every month, seeing and hearing first-hand what is happening there and having the opportunity, without the vastly varied in-tray of a leader in office, to study this phenomenon.

The two Foundations which I have established – one around Africa Governance and the other concerned with promoting respect between religious faiths and countering extremism – have also allowed me to examine the dynamics of what is happening not only in the Middle East but in the world, precisely around the challenge we now face. In the case of the Faith Foundation the connection is obvious. In the case of the Africa Governance Initiative, though it is primarily about helping African Governments implement vital programmes of change, it is increasingly clear that unless a way is found to deal with the de-stabilising power of religious extremism many African countries will be unable to make the progress they so urgently need.

So this is why I chose to do what I now do. I became convinced whilst PM that this was the issue of our time. I am even more convinced now.

1. Join the Dots. It Is One Struggle

There has been a tendency to see the conflicts happening in different parts of the world as unconnected, as driven by a collection of separate, essentially localised disputes. So we respond to each in its own way. One crisis arises and we act; another rears its head and we take another action. Or perhaps better we should describe our policy as a series of reactions. We have not yet a sense of a unifying core of strategic analysis leading to a set of actions that are governed by that core and that have coherence on a global scale.

I say that what is happening in Syria, Iraq, and across the Middle East; and what is happening in Pakistan, Nigeria, Mali, or in parts of Russia or in the Xinjiang province of China or in multiple other parts of the globe, are linked. They form different parts of one struggle. They all have their individual aspects. They all have unique dimensions. It would be odd if it weren’t so. But they have one huge and central element in common: extremism based on an interpretation of Islam which represents a clear ideology that, even if loosely at times, is shared by all these different groups of extremists.

So in every case there are distinct factors. Some are to do with long standing grievances over territory, or ethnic and tribal differences. Some are protests against central Governments and policies of repression. Some involve a dispute over the ownership and management of resources. But to deny as a result of these distinct factors, the common factor of religious extremism and of a particular ideology associated with the extremism, is wrong as a piece of analysis and dangerous in its consequences for policy.

I understand this is a contentious analysis. For example, in respect of the Middle East there has been a revival of the old Sykes-Picot debates, and whether it was the drawing of the map of the region by the British and French back in 1920 which is at the root of the present troubles. This is a quaint but ultimately fanciful explanation for what is happening. It is true of course that some of the lines then drawn have been fiercely contested. Some were at the time. True also that there are those within the region who see a chance in all the chaos, to right a perceived wrong of the past, since it is certainly true that the lines were drawn not by the people of the region but by the external powers, Britain and France.

But since those lines were put, however capriciously on the cartographers table almost 100 years ago, (and there was less caprice in it than sometimes imagined), the region has undergone a vast demographic transformation and become the centre of the world’s energy production.

For example, in 1920, the population of the UK was around 50m; France 40m; Germany 60m. Today the figures are roughly 60m for UK and France and 80m for Germany. i.e. a significant increase but not a transformation. Consider the figures for countries of the Mid East (not all obviously affected by Sykes-Picot, but all part of the same region). Egypt in 1920, 13m; now almost 90m. Syria less than 2m in 1920, by 2011, over 20m; Iraq in 1920, under 3m, now over 30m. Saudi Arabia had a population of just over 3m. Today it boasts 30m. Ancient Palestine, a hundred years ago, had less than 1m Arabs and Jews combined; now it is around 12m for Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

In 1920, oil production was minimal. The people, small in number, eked out a living often as poor farmers.

The last century has been transformative in a unique way in the Middle East. Going back would not be easy.

In any event all of these problems would be manageable if there was not violence and terror being visited on the region. Yes, there are long standing grievances and scars of tribe and tradition; but the reason why there is a living nightmare in the Middle East today, is not because of the politics of identity, but the politics of hate driven by Islamist extremism.

It isn’t the case that if we dealt with the historic issues of identity and boundaries, we would curb the extremism; it is literally the other way round: if we eliminated the extremism, we could resolve the issues of identity and borders.

The ideologies of the 20th C which caused such distress and conflict also manifested themselves in existing grievances and disputes in a variety of different ways and situations. But there is no doubt that the common factor of shared ideology crucially impacted both the manner in which conflicts arose and the vehemence with which they were conducted. Revolutionary communism had many faces. So did fascism. But their essential ideological character played a defining part in how the history of the 20th C was written, the alliances that were formed, the spheres of influence created. We have to see this ideology born out of a perversion of religious faith, in the same way.

In saying this I do not want at all to minimise the importance of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict or its effect on extremism. I believe this conflict remains absolutely central to the future of the region. I speak and write about it so much I do not want to repeat myself here.

However I think it is also now clear that this conflict, in itself, cannot explain the turmoil of the region at this present time.

By seeing the struggle against Radical Islamism as one, albeit with many different arenas of action, we then can see plainly what before has been obscured: that no strategy to counter it, will work, unless it is comprehensive i.e. unless the big picture is perceived and understood. This alone has fundamental implications for policy.

So we are right in the immediate term to concentrate on defeating ISIS. Defeating them is indeed vital. But another ISIS will quickly arise to take their place unless we go to the root of the issue and deal with this ideology wherever and however it shows itself on a coordinated global basis.

2. The Problem is Getting Worse not Better

The evidence is clear: the problem is growing not diminishing. The coverage of these issues in the Western media is led by events. The more horrific – such as the murders of the hostages – the more it intrudes on our conscience. But the truth is whilst we have focused on the hideous rampage of ISIS out of Syria into Iraq, the killing in Syria has continued, with now more dead than in the whole of Iraq since 2003; the slaughter of the innocent by Boko Haram in Nigeria goes on; the growth of militia violence in Libya is unabated (and I warn that Libya is going to become a problem potentially as bad as Syria if we do not take care); in Xinjiang in the last months hundreds have died and in the hill country of Pakistan the Army of the State fights an existential battle against terrorism, with hundreds of thousands displaced.

The timely summit on Africa held by President Obama in the early part of August swiftly became as much about the terrorist menace as about the more positive story of investment and commercial opportunity. Countries like Kenya are confronted now with an extraordinary challenge that puts at risk all the immense and substantial progress of the past years; and this has happened in the space of months.

And I haven’t even mentioned Somalia or Yemen or the Central African Republic or the travails of Central Asia. Just last week, we saw terrorist attacks in Thailand and a foiled plot in Uganda, neither country normally featuring on the roll call of extremism; and of course the arrests in Australia.

In our own countries, the biggest security threat we face: our own citizens – radicalised Muslims – who have gone to fight ‘Jihad’ in Syria, returning home battle-hardened and bent on bringing their ‘holy’ war to our own towns and cities.

In a grim harbinger of things to come, the spectre of anti-Semitism is again stalking the streets of Europe. The response of the political class has so far been confined to strong statements of disapproval. But this is an evil that requires gripping right now with firm and uncompromising action against both the perpetrators of violence and their ideological fellow travellers. When, a few days back, Chancellor Merkel took the extraordinary step of attending a rally in Berlin against anti-Semitism, accompanied by her entire Cabinet, it was a welcome response to recent events in Germany; but it was also an illustration of the seriousness of the problem.

3. The Challenge is a Spectrum not Simply a Fringe

This argument goes to the heart of the scale of the challenge and why we find it so hard to comprehend it, let alone defeat it. The problem is not that we’re facing a fringe of crazy people, a sort of weird cult confined to a few fanatics. If it was, we could probably root it out, kill or imprison its leaders, deter its followers and close the doors to new recruits.

The problem is that we’re facing a spectrum of opinion based on a world view which stretches far further into parts of Muslim society. At the furthest end is the fringe. But at the other end are those who may completely oppose some of the things the fringe does and who would never themselves dream of committing acts of violence, but who unfortunately share certain elements of the fanatic’s world view. These elements comprise, inter alia: a belief in religious exclusivity not merely in spiritual but in temporal terms; a desire to re-shape society according to a set of social and political norms, based on religious belief about Islam, wholly at odds with the way the rest of the world has developed, for example in relation to attitudes to women; a view of the West, particularly the USA, that is innately hostile and regards it essentially as the enemy, not only in policy but in culture and way of living.

This Islamism – a politicisation of religion to an intense and all-encompassing degree – is not confined to a fringe. It is an ideology (and a theology derived from Salafist thinking) taught and preached every day to millions, actually to tens of millions, in some mosques, certain madrassas, and in formal and informal education systems the world over.

It is the spectrum that helps create the fringe. A large part of Western policy – and something I remember so well fighting in Government – is based on the belief that we can compromise with the spectrum in the hope of marginalising the fringe. This is a fateful error. All we do is to legitimise the spectrum, which then gives ideological oxygen to the fringe.

Compile a compendium of all the formal and informal methods of teaching religion in Muslim communities, even in our own countries, and what you will find is much more frightening than you would think: that in many countries even those considered moderate, there is nonetheless a significant number of young people taught a view of religion and the world that is exclusive, reactionary and in the context of a world whose hallmark is people mixing together across the boundaries of race and culture, totally contrary to what those young people need to succeed in the 21st C. Only Foundations like my own and the Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund are even attempting such an endeavour – a sign of the paucity of the strategy, on a global scale, which we require.

Then go to the online following of the more radical clerics and see how some, including those with views actually very close to the fringe, have followers numbered not in thousands or even tens of thousands, but in millions. Read some of the twitter feed coming out of parts of the Mid East. Read the sermons that some of the most acclaimed radical clerics give. Mohamed al-Araifi, banned in 26 European countries for his views on women and Jews, alone has 10 million people who subscribe to his account.

So we may naturally prefer to see these people who have come to our attention in the last weeks as isolated lunatics, to be hunted down like serial killers and with their demise the problem is eradicated. Would that it were so. But it isn’t. Unless we confront the spectrum as well as the fringe, we will only eliminate one group and then be faced with another.

4. Fight the Fringe; Speak Out against the Spectrum

The fringe and the spectrum require different strategies. There is a clear difference between those with whom we disagree, however strongly, and those who are an active security threat.

We have to fight the fringe. Here are certain guiding principles of analysis when devising the means of doing so.

The first is that it is hard to envisage compromise with such people. They have no reasonable demands upon which we can negotiate. This is not like Irish Republicanism. There may be individual conflicts – like the Mindanao dispute in the Philippines – where there can be a peace agreement reached because the primary cause of conflict is local. But in general, though political engagement can reduce the support and freedom of manoeuvre of the fanatics, or divide off the merely disaffected, as was the case in Iraq up to 2010, there is no alternative to fighting and defeating the hard-core.

At a certain point, once they know superior and determined force is being used against them, some of them at least may be prepared to change. And some undoubtedly have taken up arms because of genuine grievances. So yes it is true that in Iraq after 2006, as a result of the ‘Awakening’, the political process that brought the Sunni tribes to an understanding with the Government was crucial. However so was the surge; so was the day after day, night after night, war of attrition and suppression waged with such courage by US, UK and other forces.

The second is that the moment they cease to be fought against they grow; and fast. ISIS now controls a territory in Syria and Iraq larger than the size of the UK. Just think about that, let its full ghastly implications sink in. This is right on the doorstep of Europe. Boko Haram was reported recently to have taken the Northern city of Bama in Nigeria. Weapons from Libya together with funding have increased their reach and firepower. Libya itself is in the grip of warring factions where the risk is not just the vanquishing of internal stability, but the export of arms, money and extremist personnel across the world. As fighters are pushed out of Yemen, they go across to Somalia and from there across west to the northern parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. With territory comes the opportunity for these groups to gain money through extortion and kidnapping, to access resources, and build manpower.

The third is that whilst terror is upright and busy, it is impossible for any country to solve its everyday challenges and embrace with confidence the future. It is not simply the act of terror and the fact of carnage that de-stabilises a nation. It is the fear, the chaos, the tremor throughout the whole of society, deepening fault-lines, exacerbating existing divisions and giving birth to new ones. That is why it has to be fought against with vigour and without relenting.

Fourth and hardest of all, because the enemy we’re fighting is fanatical, because they are prepared both to kill and to die there is no solution that doesn’t involve force applied with a willingness to take casualties in carrying the fight through to the end.

This is where we get to the rub. We have to fight groups like ISIS. There can be an abundance of diplomacy, all necessary relief of humanitarian suffering, every conceivable statement of condemnation which we can muster, but unless they’re accompanied by physical combat, we will mitigate the problem but not overcome it.

Airpower is a major component of this to be sure, especially with the new weapons available to us. But – and this is the hard truth – airpower alone will not suffice. They can be hemmed in, harried and to a degree contained by airpower. But they can’t be defeated by it.

If possible, others closer to the field of battle, with a more immediate interest, can be given the weapons and the training to carry the fight; and in some, perhaps many cases, that will work. It may work in the case of ISIS. There is real evidence that now countries in the Middle East are prepared to shoulder responsibility and I accept fully there is no appetite for ground engagement in the West.

But we should not rule it out in the future if it is absolutely necessary. Provided that there is the consent of the population directly threatened and with the broadest achievable alliance, (to which I return below), we have, on occasions, to play our part. To those who say that after the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq, we have no stomach for such a commitment, I would reply the difficulties we encountered there, are in part intrinsic to the nature of the battle being waged. And our capacity and capability to wage the battle effectively are second to none in part because of our experience there.

However we’re not talking here about armies of occupation. We are, in certain situations where it is necessary and subject to all proper limitations, talking about committing ground forces, especially those with special capabilities.

What helped turn the tide back in favour of Assad in Syria was the entry into the conflict of Iranian backed Hezbollah. They fought the ground war. They took casualties. On one account I was given, in a short period before the end of 2013, they took more casualties than the UK in the whole of Iraq in the years we were present there. For the same reasons extremist groups rose to prominence in the Syrian opposition because they were prepared to fight where the battle was hottest.

I know as well as anyone all the difficulties in advocating even the contemplation of such a course. It may require change whether in NATO or within the framework of European Defence to improve the force capability we have presently and our ability to work in alliance with others. It may even require a new configuration of combat forces altogether. But I repeat: you cannot uproot this extremism unless you go to where it originates and fight it.

The spectrum is a different matter. Here the most important thing is to expose it, to speak out against it, to make sure that at each point along the spectrum the proponents of this ideology are taken on and countered; but also be prepared to engage in dialogue and to acknowledge, as has been the case in Tunisia, that some of those on this spectrum may be willing to leave it. So there should be openness in our attitude, but the total absence of naivety. To engage successfully, we have to be willing to confront.

We are not doing this as of yet. The truth is that Islamism, unless fundamentally reformed, is incompatible with modern economies and open-minded, religiously pluralistic societies. This truth has to be recognised. This is not to say that it should be subject to oppression. Certainly in our types of society, people are perfectly entitled to hold views that we believe are destructive to our way of life and that we profoundly disagree with. Provided that that they express them within the law, that is their right.

But it is also our right to point out why they are indeed incompatible with all we hold dear. And it is our duty, if we believe in what we say we do, to take on the argument with vigour and to watch with vigilance to see that Islamism does play by the rules in our own country. And where, as so often abroad, they operate outside the law and seek to subvert progress we should be keen to expose them and be loyal to those, in these countries, who share our way of thinking.

This is why I argue that in the Middle East and elsewhere, we should not view the ideological struggle between Islamists and those who want open-minded societies, as one in which we’re neutral. There is a side we should take. And we should do so with energy, because they need our support.

This is why what has happened in Egypt is so important and what will happen in the future is vital; including to our own interests. Of course there will be disagreements, sometimes strong ones, – as over the jailing of the Al-Jazeera journalists or the death sentences handed down to hundreds of people in one ruling. I am not suggesting we do not criticise where it is right to do so. This is not advocating a policy of ‘turning a blind eye’ to human rights abuses. It is simply realising that in the complexity of the situation the country finds itself, we have to be the friend onside and supportive – though prepared to speak critically – not the distant commentator blind to the reality of the assault on its way of life by radical Islamism which this ancient and proud civilisation of Egypt faces.

Governments are not NGOs. We have to represent and advance broad strategic interests in defence of our values. It is massively to our advantage that President Sisi succeeds. We should help him. We should not make the mistake of dealing with the Muslim Brotherhood as if it were merely an Arab version of the Christian Democrats. It isn’t and there is little sign it ever will be.

World-wide, we should be on the look-out for where there is evidence that Islamist organisations are on the march. Those that fund and support them should know that we’re watching, should know that what they want hidden, will instead be exposed to the light.

5. Support Modern-minded Muslim Opinion. They Are Our Allies

One of the tragic myths of the past years has been the idea in the West – almost like a new Orientalism – that Arabs in particular and even Muslims in general are irredeemably lost in the mire of religious and ethnic dispute, that their mind-set is incompatible with democracy, that the whole thing is really about Shia vs Sunni, that they’re condemned by some invincible force of history to be in conflict and mayhem.

You still hear people say ‘Arabs think this’ or ‘the feeling in the Muslim world is that’. This is no more accurate than saying ‘the British think this’ or ‘Christians think that’. The fact is that opinion on most issues in the West is divided. There is a plethora of views. It is no different today in the Arab or Muslim world.

The true significance of the so-called Arab Spring – in reality a series of revolutions across the region – has not been properly understood in the West. Having been initially naive about the ease with which societies creaking under oppressive regimes and out of date institutions could make the transition to modernity, we’re now in danger of making the opposite mistake, believing that the instability that has followed these revolutions shows the inherent incapability of those societies to adapt and change.

What we’re actually witnessing is an agonising, immensely challenging but profound transition away from the past to the future. The regimes ultimately collapsed under the weight of their own contradictions, the biggest one being the contradiction between the need for a modern economy and well educated workforce in societies of burgeoning populations; and the reality of a system totally unsuited to such an economy and the absence of such education. Islamism often became the way that people protested against the regime under which they were groaning. When the old order passed away or came under attack, there was then a struggle between those who wanted a modern economy and society to come into being and those who wanted to turn instead to a religiously based order.

This is still the essential battle.

The lesson from Iraq or Afghanistan is that where it is possible to have a process of evolution, then that is the optimal outcome, because the instability which accompanies revolution and the ousting of the old order is so difficult to bring under control and in the disorder that follows revolution, the wrecking forces of extremism have the opportunity to get out on parade.

This is why in respect of both Libya and Syria, as I argued at the time, it would have been better, if it had been possible, to have had an agreed process of change even if it meant for a transitional period leaving the existing leadership in place as the change happened.

However where the Western debate misses the point is in thinking that the systems that have been in place or still are, were or are sustainable for the long term. In other words when people say things like – maybe it would have been better if Saddam were still governing Iraq or Gaddafi in Libya or now want us suddenly to ally ourselves with Assad because then at least we would have stability, they fail to understand one crucial point: the people living under those regimes won’t accept it. The promise of stability of such a kind is hollow. This is the significance of the revolutions. So leave aside the actual misery of the people under those Governments. What the events following 2011 show is that the choice is revolution vs evolution. The status quo is not on offer. That is where the Islamists and the liberals agree.

The problem with the modern-minded elements – if we can describe them like that – is that they are numerous but not organised; whereas the Islamists are both numerous and well organised.

The important thing now is that we recognise that this struggle is ongoing, that it is not lost, and that we should do all we can to ally ourselves with those who want to get to the future but face inordinate challenges in doing so.

This issue – so connected with the debate inside Islam – cannot in the end be won other than by Muslims. But we have both an interest in the outcome and a role in supporting those who realise that the only hope for the future lies in a world in which different faiths and cultures learn to live with each other in mutual harmony and respect.

6. East and West Should Work Together

One thing is irrefutable: this is a challenge which East and West share. The extremism and its attendant ideology have caused serious attacks and terror in both Russia and China to say nothing of course of India. So the great powers of the East, without doubt, desire the right outcome to this battle as much as us.

I completely understand the hesitation of the West at any notion of an alliance in any form with Russia. The events in Ukraine cast their long and dark shadow. For the avoidance of doubt, let me make it clear I am not suggesting that we reduce our pressure on Russia in any way in respect of Ukraine. I am not contemplating some omnibus deal in which in return for help against the forces of Islamism, we yield on the proper protection of the people of Eastern Europe.

I am making two points. The first is that the main security challenge of the 21st C remains the Islamist threat. I do not minimise the risk of a more conventional confrontation between the big powers such as we saw in the 20th C. It is possible that Russia, relinquishing the old Soviet armour, decides to wear new battle garb forged by exaggerated sentiments of nationalism and to take it to the point of all-out war. We should certainly not be complacent about the danger.

But my belief is that the 21st C will not repeat the pattern of earlier times. The stakes are too high; the lessons of history too unambiguous. I think the principal threat today will come from non-State actors or from rogue States. Look at the death and terror of the past years since 9/11, and most of it has come from these sources. Radical Islamism is the issue.

On this issue, we need the East as partners. We need them as partners for many reasons to do with effective action against the threat, to coordinate, to cooperate and to disrupt the activities of the Islamists. But we need them for another reason. As will be very obvious reading the propaganda of the extremists and those further along the spectrum, essential to the propagation of their world view is the notion that this is a fight between the culture of the West and Muslims.

We need to have it absolutely clear that this is false. It is actually a global battle between those who believe in religious tolerance and respect across boundaries of faith and culture; and those who don’t; between those who accept globalisation and those who don’t, not because globalisation produces injustice, but because it necessarily involves the mixing and mingling of people.

In making this case, it is important – I would say essential – to have East and West lined up together. India should have a central part in any such alliance of nations East and West, because of its size, its experience and its religious composition.

7. Education is a Security Issue

This is the question upon which the least is said in this whole debate, which is both perplexing and alarming. Each and every day the world over, millions, even tens of millions of young children are taught formally in school or in informal settings, a view of the world that is hostile to those of different beliefs. That world view has been promulgated, proselytised and preached as a result of vast networks of funding and organisation, some coming out of the Middle East, others now locally fostered. These are the incubators of the radicalism. In particular the export of the doctrines of Salafi Wahhabism has had a huge impact on the teaching of Islam round the world.

I am not saying that they teach youngsters to be extremists. I am sure most don’t. But they teach them to take their place on the spectrum. They teach a view of the world that warps young and unformed minds, and places them in a position of tension with those who think differently.

If we do not tackle this question with the honesty and openness it demands, then all the security measures and all the fighting will count for nothing. As I have said before, especially foolish is the idea that we leave this process of the generational deformation of the mind undisturbed, at the same time as we spend billions on security relationships to counter the very threat we allow to be created.

We need at the G20, or some other appropriate forum, as soon as we can, to raise this issue as a matter of urgent global importance and work on a common charter to be accepted by all nations, and endorsed by the UN, which makes it a common obligation to ensure that throughout our education systems, we’re committed to teaching the virtue of religious respect. This doesn’t mean an end to religious schools or that we oblige countries to teach their children that all religions are the same. Catholic schools will continue to teach their children the virtues of the Catholic faith. Muslim countries will continue to teach their children the value of being Muslim. But we should all teach that people who have a different faith are to be treated equally and respected as such. And we should take care to root out teaching that inspires hatred or hostility.

The work which my Foundation does – now in 30 different countries – shows clearly the benefits of education programmes which teach young people about ‘the other’ in ways which enhance mutual respect. There is plenty of evidence such programmes work. We just need to act on it.

This should be a common global obligation, like action to root out racism or action to protect the environment. Nations should feel the pressure to promote respect and to eradicate disrespect.

It follows from all the above that what is required is a major overhaul of policy. This should be done without recrimination or unnecessary dispute about the past. There will continue to be fierce debate about the post 9/11 decisions particularly Iraq. But the fact of the Arab revolutions since 2011 in the Middle East and North Africa and the obvious prevalence of the Islamist problem far beyond the boundaries of either Iraq or Afghanistan, mean that this issue has to be re-thought and debated anew.

Neither should anything here be taken as a criticism of the new generation of leadership in the West. On the contrary I sympathise enormously with the challenge which it is their grave responsibility to meet. This is a problem of the first magnitude. It dismayed and often disoriented those of us before them. It will continue well beyond the present leaders. Certainly we made mistakes. And for sure our understanding frequently fell short. This is the way of things when new and original threats of great significance arise. But now we need to pool our energies and focus our attention, learning from the past so as better to address the future, without a narrow or partisan political debate, without attempts to discredit or decry, but with the combined rigour of analysis and action the situation now urgently demands.

This essay originally appeared on religionandgeopolitics.org, an online resource by the Tony Blair Faith Foundation that provides detailed analysis of religion and conflict.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com