Some maintain that the Pentagon is a self-licking ice cream cone, dedicated to its own preservation. If that’s true, it’s also worth noting that an expanding terrorist state is an oxymoron—one that will eventually collapse from its own internal contradictions.

The fact that the U.S. and its allies attacked a financial hub of the Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) on Tuesday–the first day of strikes in Syria—and spent Wednesday and Thursday bombing its oil-production facilities, highlights ISIS’s predicament.

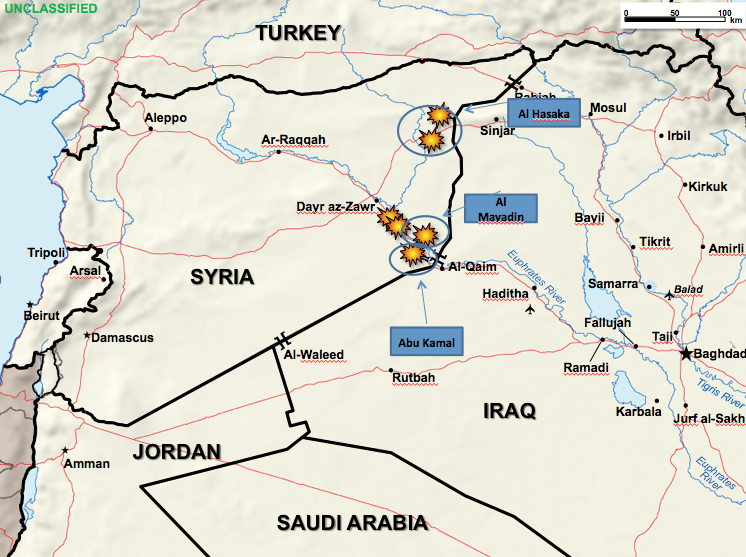

Unlike a smaller terrorist organization—al-Qaeda, for example—ISIS now occupies, and purports to govern, a wide swath of desert straddling the Syrian-Iraqi border. It needs the estimated $2 million a day it’s grossing by smuggling oil because many, if not most, of its 30,000 fighters are in it for the cash, not the ideology. But the refineries represent only a small slice of ISIS’s oil revenues. It makes most of its money from crude oil, and the U.S. has refrained so far from attacking oil fields in the region.

If the money eventually dries up, Pentagon officials believe, many ISIS fighters will head back home. The terrorists control about 60% of Syria’s total oil production, according to a Syrian opposition estimate.

“Substantial uncertainty pervades our understanding of the mechanics, volume, and revenue associated with the terrorist group’s black market petroleum operations,” the Senate Energy Committee said in a report released Wednesday. “Depriving ISIS of whatever dark revenue pool it generates from its sales of oil will put additional strain on an organization with little capacity to expand its oil field operations.”

Wednesday’s attacks by six U.S. and 10 Saudi and United Arab Emirate warplanes took all 12 targeted refineries offline, U.S. intelligence believes. “They’re not going to be using these refineries for some time,” Rear Admiral John Kirby, the Pentagon spokesman, said. “We’re trying to remove the means through which this organization sustains itself.”

Generating such revenue requires industrial-like facilities, which can go from money-makers to targets in the flash of GPS-guided bomb.

That highlights an edge the U.S. and its allies have on ISIS. Sure, the terror group’s recruits, armed with AK-47s and pickup trucks sporting machine guns, can take over small refineries sprinkled across eastern Syria. But once they have them, they can’t keep them running under aerial assault.

Pentagon officials acknowledge they don’t know how long it will take for the lack of oil money to begin having an effect. But they know what they are looking for. “We’ll know when they have to radically change their operations,” Kirby said. “We’ll know when we can see that they no longer are flowing quite as freely across that [Syrian-Iraq] border. We’ll know when we have evidence that it’s harder for them to recruit and train, or they just aren’t doing as much training and recruiting.”

That’s the conundrum ISIS faces as it tries to expand and become a functioning state: so long as the rest of the world isn’t willing to let that happen, ISIS eventually will have to revert to becoming a poorer and smaller—though still dangerous—group.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com