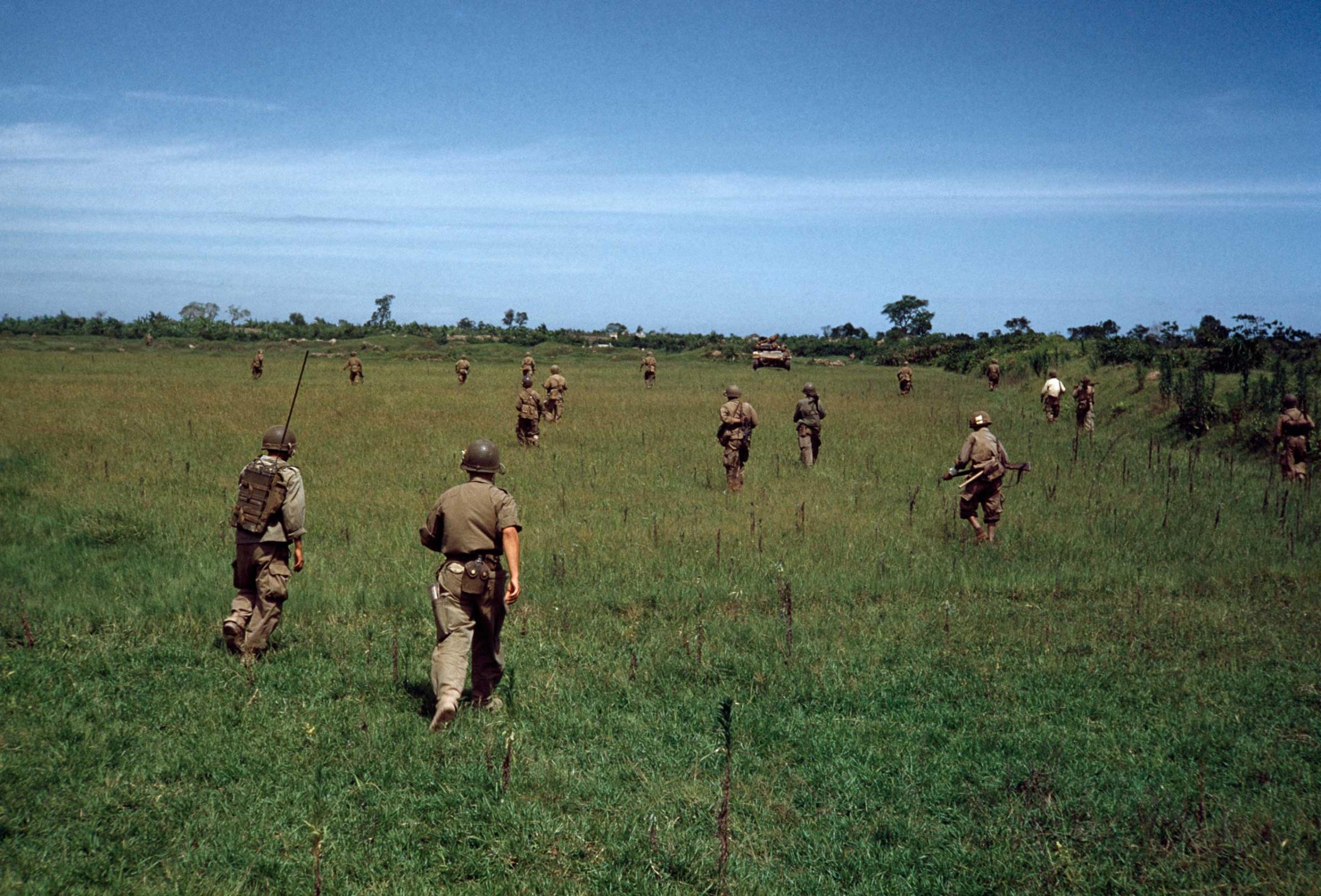

For many, Robert Capa is the quintessential photojournalist. Honest, insightful, poetic and fearless, Capa’s work granted license and creative inspiration to any and all who followed in his footsteps. Despite changing trends in photographic storytelling through the decades, Capa’s images endure. Ask any photographer — or most anyone with a sense of photography, history or culture, for that matter — and chances are pretty good they’ll be able to cite one or more of Capa’s black and white photographs as models of the craft: “Falling Soldier,” the D-Day landings, the Liberation of Paris.

It’s just as likely, though, that very few will realize that his color work is phenomenal, too.

A new show at the International Center of Photography in New York offers an extraordinary chance to see more than 125 unpublished and unseen color photographs by Capa.

According to Cynthia Young, the show’s curator, ICP holds more than 4,000 color Capa transparencies of varying formats — 35mm, square format, even 4×5 sheet film. “He really had two cameras around his neck at all times — three even, often in two different formats,” Young tells TIME. Featuring work from the 1930s through the ’50s, the color photographs celebrate Capa’s eye for war, fashion, culture, even portraiture.

It’s not clear why Capa shot some photographs in black and white and others in color. Capa always shot both, Young says, and he was well aware that magazines would pay more for color. “He could sell the color for more than a black and white picture,” she said. “It was more exotic and [garnered an] exclusive for certain stories.”

Splashing color into some of his iconic (and previously monochrome) looks at the 20th century’s armed conflict, Capa fans will be surprised by the vibrancy of the black in white scenes now generously revealed in color. And it isn’t just images of destruction that surprise. “After Capa’s war narratives,” she explains, “it’s often hard [for the public] to fit his post-war images into the Capa narrative.”

As to why these photos haven’t been seen before 2014, Young points to shifting attitudes towards color photography. “People are interested again in the origins of early color work,” she says, explaining that color used to only be the “domain of amateurs.” Young also notes that technology had improved the museum’s ability to restore the aging and often fragile negatives to their original dynamic range.

In 2004, Magnum felt it pertinent, on merit alone, to publish a book of Capa’s color work. Sharing the same name as the ICP show a decade later, the book highlights color work Capa made on a ship convoy steaming across the Atlantic early in WWII. The book and show also highlight stories Capa shot at the homes of Ernest Hemingway and Pablo Picasso, showing the legendary creatives enjoying time with their families.

“He wasn’t known as a portrait photographer, but the images are stunning,” Young explains. “They’re only possible with big loving personality Capa had.”

Capa in Color is on view at the International Center of Photography from January 31 through May 4, 2014.

Vaughn Wallace is the producer of LightBox. Follow him on Twitter @vaughnwallace.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com