Inside the hospital wing of Alcatraz, which is typically closed to the public, there are two adjacent rooms the size of closets. Together they make up the entire space officials dedicated to treating mentally ill prisoners before the notorious penitentiary was shuttered in 1963. And thanks to the Chinese artist and rights activist Ai Weiwei, for the next seven months those rooms will be very loud.

This paltry psych ward now holds one of seven site-specific installations in four locations around the island that Ai – everyone calls him Weiwei – has taken over for a new exhibit opening Sept. 27. Cheekily titled “@Large”, the installations, which remain on view through April 26, are designed to use the setting of an infamous prison to explore issues of human rights, punishment and the loss of freedom.

In one of the two spartan rooms plays a loop of Tibetan chants, in the other an American Indian song intoned by the Hopi tribe—thumping tracks that resonate in one’s ears like voices might in one’s head. Both are meant to remind visitors of how confined and oppressed those peoples have been at times throughout history. The latter is also reminding America, in particular, about the imprisonment of Hopi men at Alcatraz who refused to send their children away to government boarding schools in the late 19th century. “That was the darkest time,” the National Park Service’s Michele Gee says about jailing the island’s earliest prisoners of conscience. Weiwei calls that particular piece “Illumination.”

There are plenty of impressive things to note about this unprecedented exhibition. One is that the 57-year-old Weiwei designed and built his elaborate pieces without ever setting foot on the island. A vocal critic of the Chinese government, Weiwei has not been permitted to leave the country since being detained for 81 days in 2011 on tax evasion charges that were brought against him after he had conducted a lengthy investigation of government culpability in the shoddy construction of schools that collapsed in China’s 2008 earthquake, killing thousands of children. Another is the installations themselves, like “Trace,” which consists of 176 portraits of political prisoners fashioned out of 1.2 million Legos; or “With Wind,” an intricate dragon that fills an entire room in the form of some 100 hand-painted kites that hang like dominoes from the ceiling.

Less obvious is how logistically complex the project was, which not only involved getting architectural plans and videos and photographs to the artist but also seeking the approval of government agencies going all the way up to the State Department. Though the project was first conceived in 2012, the actual assembly of @Large took just nine months. And the person who should be credited for putting all the works together so quickly (sometimes literally putting them together, after carrying them across San Francisco Bay by rented barge at night) is curator Cheryl Haines. Haines is a fixture in the San Francisco art world and executive director of a non-profit called For-Site, which exists to install ambitious art in unexpected places. And she is the person who suggested to Weiwei the idea of doing an exhibition in Alcatraz while visiting him in Beijing. “Of course it’s difficult for him that he doesn’t have personal freedom and that he’s not able to come,” she says, currently sporting blue hair in an attempt to keep her calm through the storm. “But Ai Weiwei is incredibly adept at understanding the built environment … and he welcomed the challenge.”

Less obvious still may be the fact that agencies of the U.S. government, which to some extent is lumped in with more egregious human-rights violators in the exhibit, would work so hard to highlight the dark underbelly of American history, from the treatment of American Indians to the dire conditions of Alcatraz in its days as a prison. Because of the not-always-great relations between the U.S. and China, the National Park Service, which oversees Alcatraz Island and its facilities, made the choice to seek permission from the State Department before giving a Chinese political dissident one of the nation’s most popular visitor sites to use as a stage. “We knew from the get go that his belief in self-expression and his values are part of his art,” says Greg Moore, CEO of the non-profit Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy that staffs Alcatraz. “Ai Weiwei takes us beyond the gangster years into something that’s not only part of our history but part of our present.”

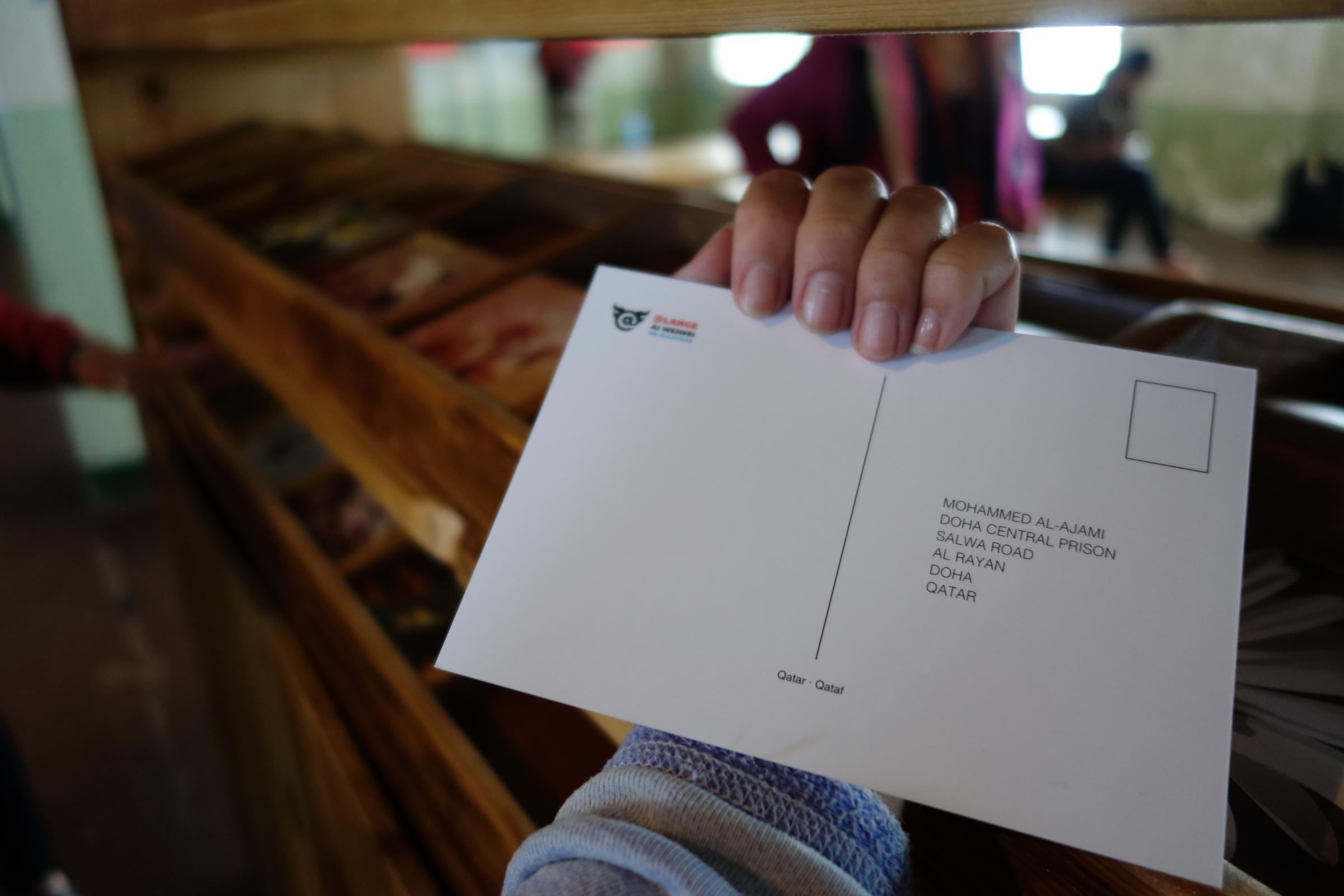

Also in the hospital wing is “Blossom,” which consists of porcelain flower sculptures snugly fit into existing amenities like bathtubs and sinks. The work, the curator says, might be interpreted as an offering of sympathy to those who are imprisoned or an allusion to China’s Let One Hundred Flowers Bloom Campaign in 1956, a time when free expression was briefly tolerated among citizens, before being abruptly and ruthlessly suppressed again. In the Dining Hall, the single exhibition space that is normally open to the public, Weiwei offers visitors the chance to send an actual token of sympathy to political prisoners who are still incarcerated in various parts of the world—via postcards that are covered in symbols and birds of the prisoners’ respective countries and are pre-addressed. Aides working on the “Yours Truly” installation — some of the 47 trained to guide visitors through the exhibition — will put the cards in the mail once they’ve been written.

Weiwei plays with sound again in Cell Block A, where songs and speeches of the oppressed or imprisoned play out of each cell. Inside is a spare stool for a listener to sit, and outside is the name of the prisoner. Installing the speakers required using a hallway behind the block, as Haines and her team were not allowed to remove so much as a screw on the vents from which the sounds of “Stay Tuned” emanate.

One of the most uncomfortable and eerie no-go zones that visitors will be let into for the exhibition is the gun gallery, a narrow hallway where armed guards once walked above rooms of prisoners, ready to shoot if necessary at a signal from an unarmed guard keeping watch on the ground. This is the walkway from which viewers will see “Refraction,” a sculpture that looks like a metal bird stuck in mid-flap, unable to fly under a suffocating ceiling.

Much of the challenge in getting @Large off the ground, Haines says, was making sure not to disturb even the broken glass in window frames of the historic buildings as the team installed Weiwei’s pieces. (The park did, however, install Plexiglass to protect people from the shards.) Part of the reason the exhibition is opening in September, after the height of tourist season, is that marine birds like cormorants nest there during the summer, and “ecological resources” were not to be disturbed either. Still, the exhibition has led to change on Alcatraz; for the first time there will be WiFi on the island, which the artist wanted so that people could share experiences of @Large on social media. And Moore says that letting people into the specially opened spaces may prove a “pilot” for permanently opening them in the future. There is also hope, Haines says, that the exhibit will lure more locals to join the roughly 1.5 million visitors who boat to the island each year, Bay Area residents who might have some money burning in their pockets that could go to the National Park Service or local arts programs.

The bright colors and delicate shapes of @Large somehow highlight the drab, sad conditions of the prison, like a child holding a bright balloon in the middle of a blackened, post-apocalyptic landscape. “If you look at the actual objects, they’re layered but beautiful,” says Haines, who previously worked with Weiwei on an exhibition in which various artists crafted abstract homes for native animals of the Golden Gate area. Ai chose sweet, cylindrical blue-and-white porcelain houses, and For-Site hung them temporarily in the forest for screech owls.

For this project, Haines spearheaded the fundraising of more than $3.5 million dollars, so that it would not cost taxpayers or the overburdened Parks Service a dime. It won’t cost visitors anything either; access is free for people who book regular tours to Alcatraz through April. If there’s demand, Haines says, they may also organize a special boat just for Weiwei pilgrims.

“With @Large, the conversation has broadened to encompass more types of human rights around the world,” she says. “We keep upping the ante, clearly.”

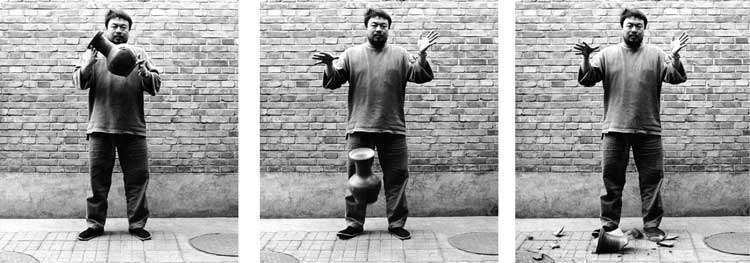

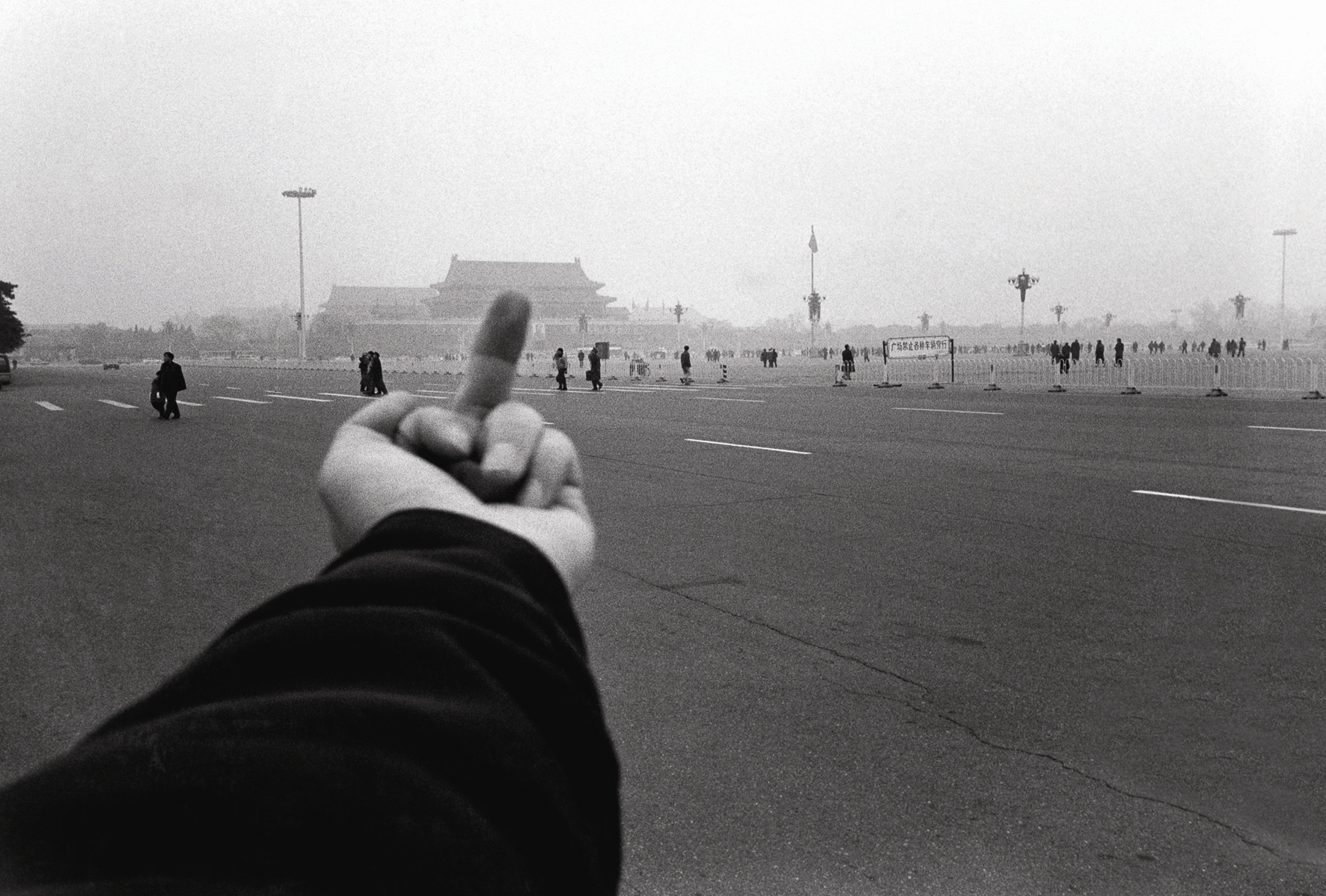

These Are Some of Ai Weiwei’s Most Influential Works of Art

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com