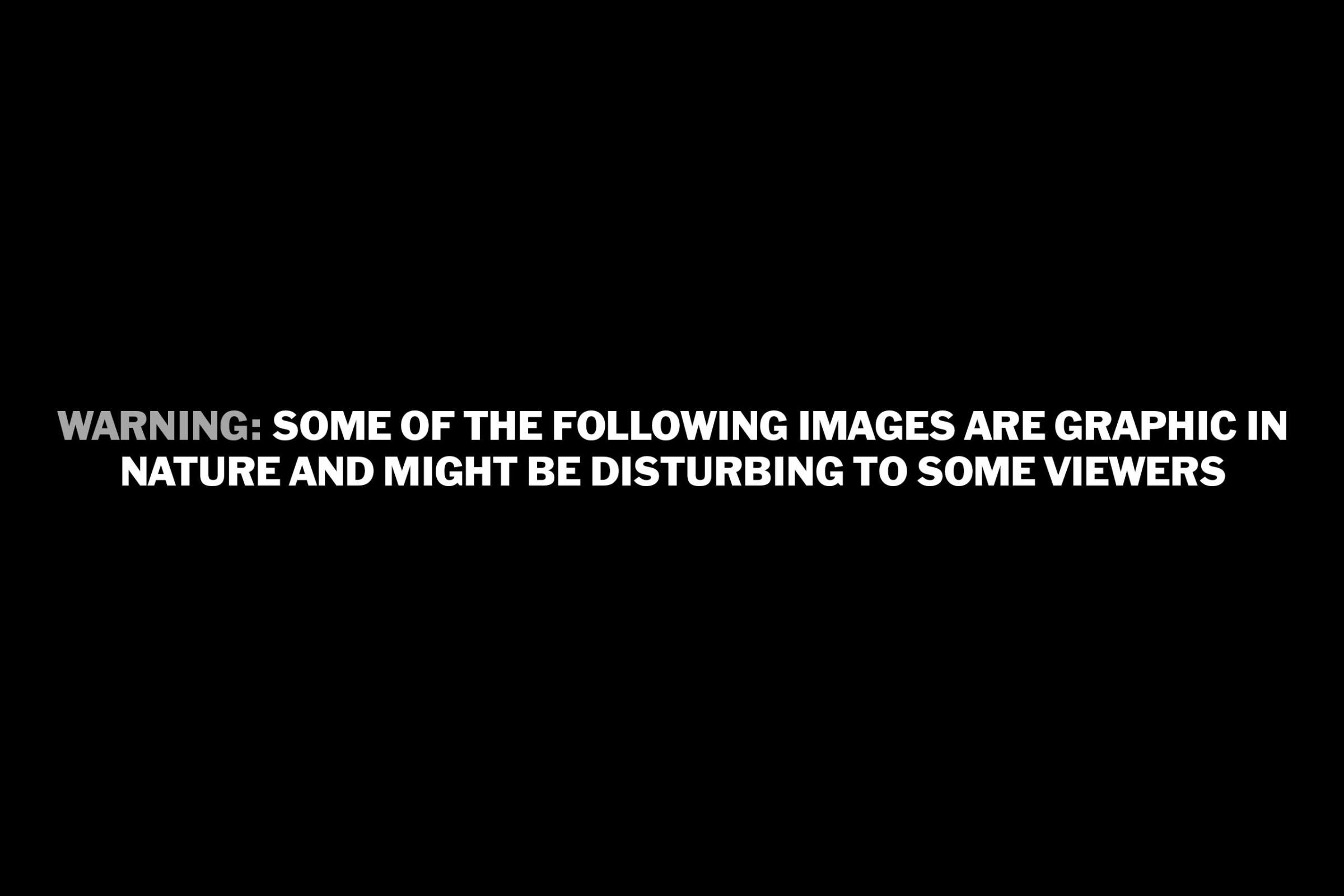

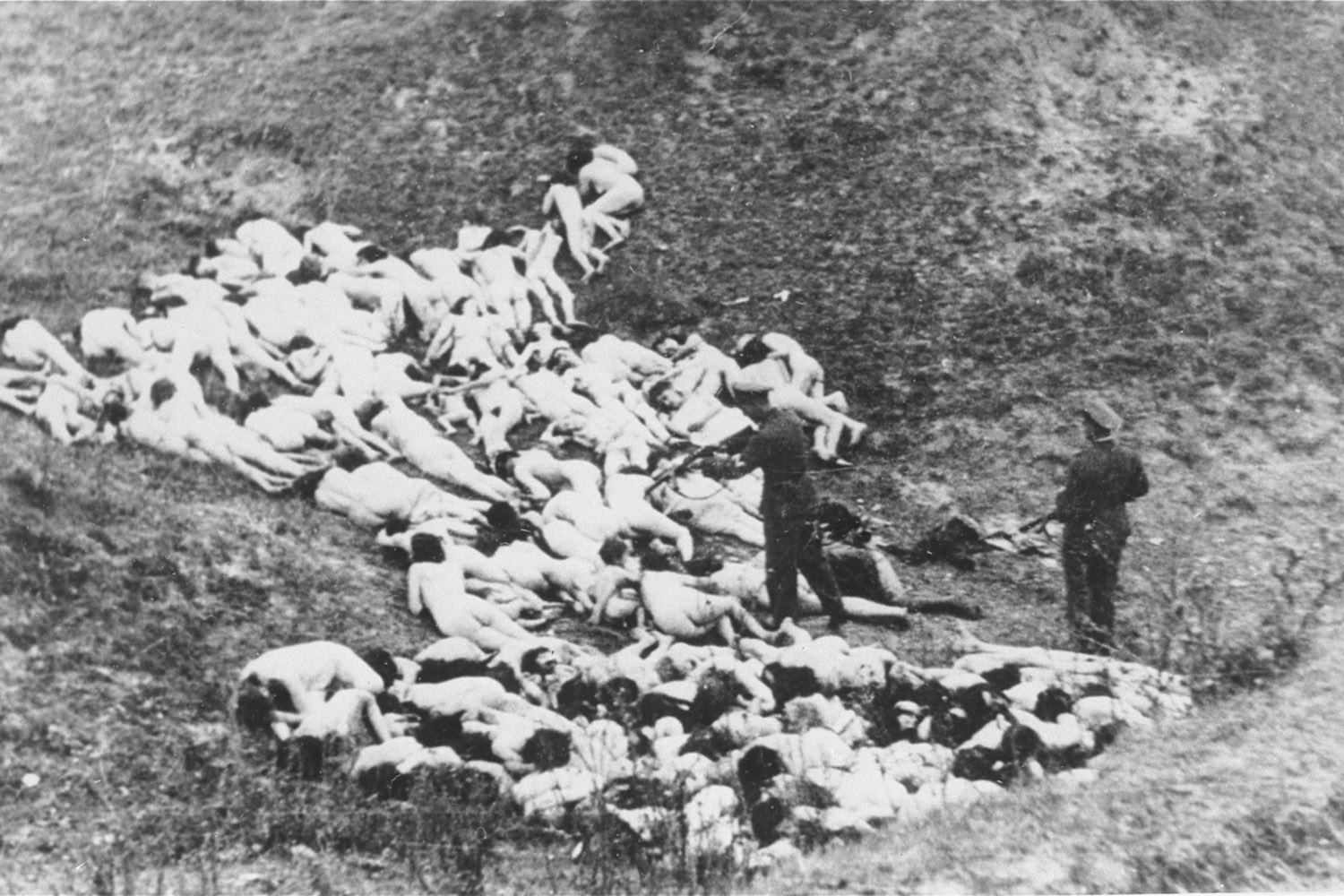

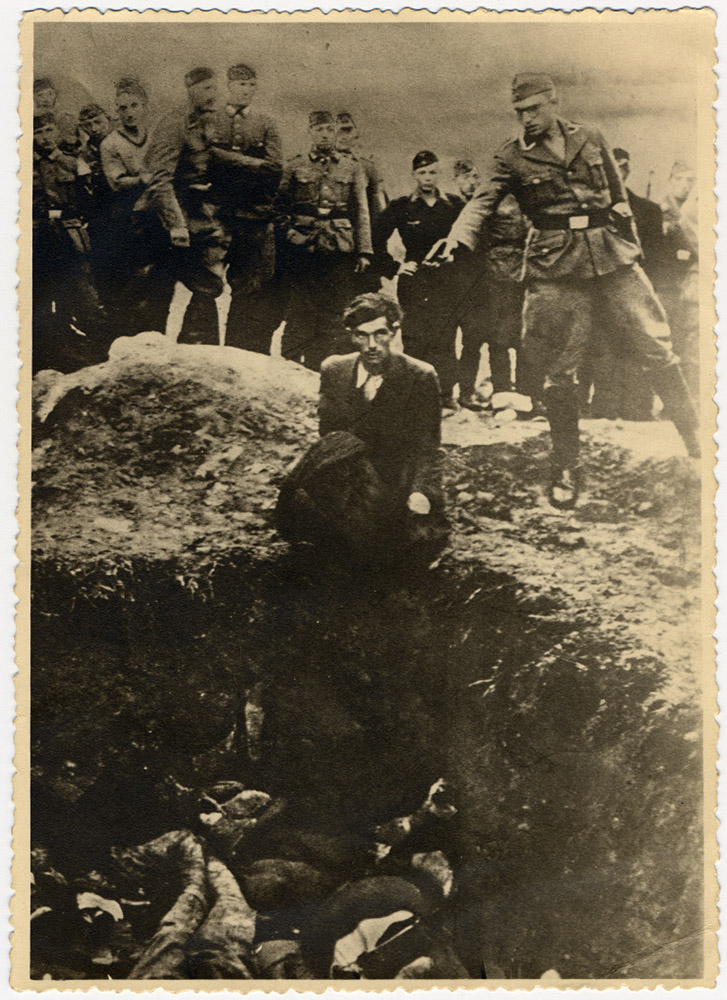

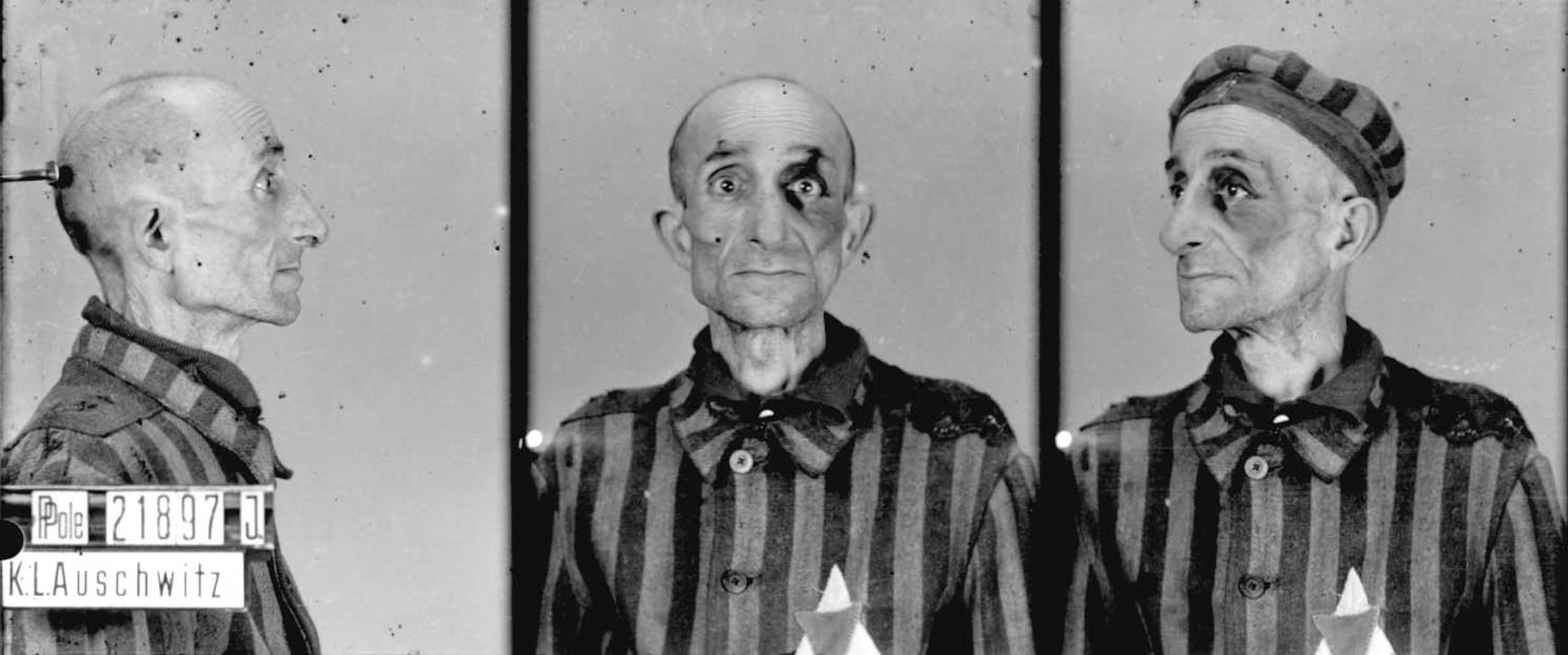

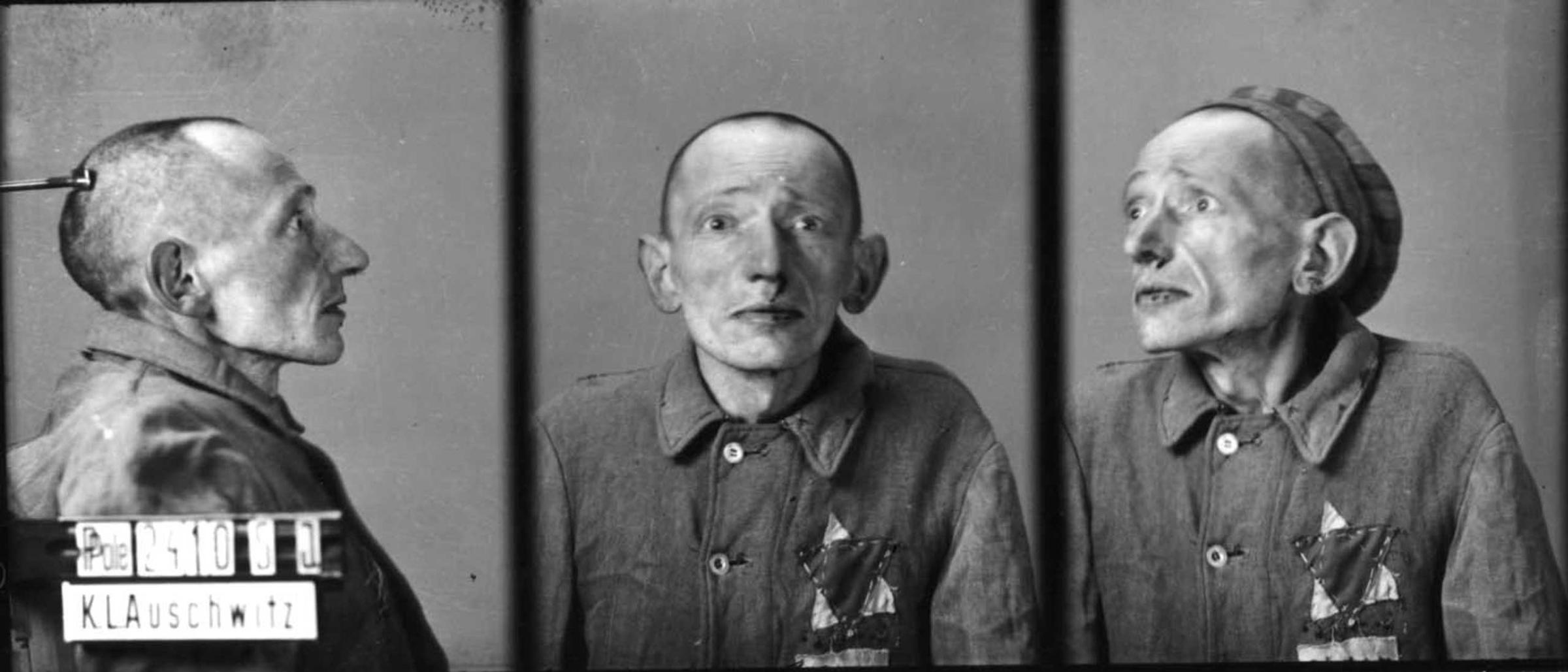

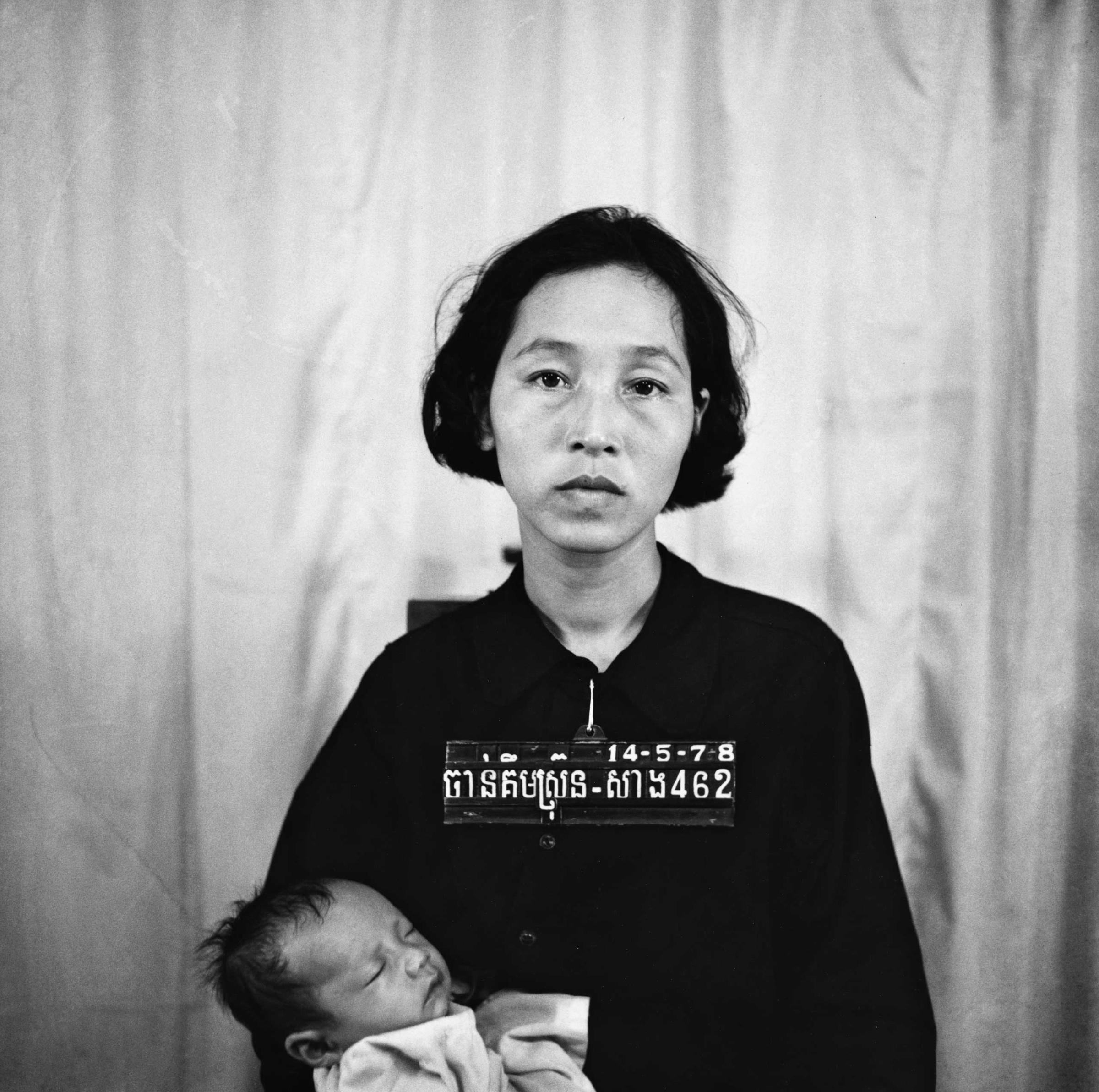

During the last century, photographs of mass murder in Nazi Germany, Argentina, Cambodia, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia seared the civilized conscience with their revelations of barbarity. Some of the more irrefutable images were the most clinical, eschewing the empathy of the documentary observer while cataloging the horrors as a form of record-keeping, leaving it to the viewer to arrive at the moral calculus of each atrocity.

Given that extensive image archives tend to emerge only after the fact, a crushing sense of moral failure on the part of the viewer could be mitigated by a sense that, had the international community only known of the atrocities sooner and in such visceral detail, a more active response might have been provoked. Many documentary photographers today continue to take enormous physical and psychological risks for just this reason: to expose contemporary abuses so that, the expectation endures, something may be done to rectify them.

In this century, however, with trillions of photographs and videos competing for one’s attention online, and news media (as well as governments) less capable of prioritizing issues from among the bewildering array evoked, specific imagery is often unable to focus the public on subjects of larger importance. No iconic imagery has emerged from the war in Afghanistan, the longest in U.S. history, to provoke a societal debate akin to the photograph of the girl being napalmed or the man being executed on the street at point-blank range during the Vietnam War. The most pivotal imagery from the recent U.S. military involvement in Iraq remains the party-style pictures of torture from Abu Ghraib prison, made not by photojournalists but by the implicated soldiers themselves. Even domestically, photographs of twenty elementary school children and six adults gunned down in Newtown, Connecticut, did little to move either the Congress or local governments towards more effective gun control. Will images of climate change ever emerge that will get governments to realistically confront numerous environmental challenges?

But shouldn’t the existence of 55,000 photographs by the Syrian military police documenting the deaths of some 11,000 detainees who had been executed, and in many cases tortured, still provoke widespread condemnation, particularly in a conflict that is ongoing where millions are still at risk? In this “age of image” (or is the label ironic?) a recent report by a distinguished group of experienced outside experts authenticating this enormous cache of smuggled photographs has met with only a muted international response. Some feel that the photographs, only a few of which have been released so far, come as no surprise, or that previous images, such as those of chemical attacks on civilians, had already confirmed the Syrian government’s criminal behavior. Others point to vicious actions on the part of rebel groups as a rationale supporting the government’s brutality, or contest the credibility of the photographs. There is also a sense that the international community will not be drawn into another war no matter what the photographs might demonstrate.

The photographs, showing “signs of starvation, brutal beatings, strangulation, and other forms of torture and killing,” according to the outside forensic team which also verified that the photographs had not been digitally manipulated, have not so far served as a clarion call to conscience. This report even explains the governmental logic behind the making of the photographs: “The reason for photographing executed persons was twofold: First to permit a death certificate to be produced without families requiring to see the body thereby avoiding the authorities having to give a truthful account of their deaths; second to confirm that orders to execute individuals had been carried out.” In each case the cause of death was to be reported as “either a ‘heart attack’ or ‘breathing problems,’” with the bodies, a great majority of them who were young men who would be unlikely to have such health problems, buried in rural graves. Caesar, the pseudonym for the Syrian police photographer who smuggled out the bulk of the images, “informed the inquiry team that there could be as many as fifty (50) bodies a day to photograph which required fifteen to thirty minutes of work per corpse.”

For several decades a global war of images has been intensifying. It is a conflict in which how one spins the images of the events may trump the actual outcomes of the events themselves. Rather than allow photographers to contradict the relatively optimistic assessments of governmental officials, as happened to the U.S. during the Vietnam War, photographers have been banned from conflict areas or embedded with troops, restrained from publishing certain kinds of photographs not deemed to be in the military’s best interests. Simultaneously journalists are increasingly being targeted, kidnapped and killed by warring parties, some of which are also recording decapitations and other attacks to foment terror in their own image war.

An older social contract that surrounded the making and distribution of documentary photographs assumed the willingness of the viewer to accept the photograph’s reality as well as its invitation to a response, both personal and societal. One might feel disgusted or angered, or a whole array of other feelings, but the relationship between image-maker and viewer, particularly when concerning war and other forms of violence, was meant to be a serious one pivoting around issues of life and death.

But in an ongoing war of images, where every photograph proferred may be suspect, this social contract becomes frayed. The release of this report on the death of thousands of executed detainees just as peace talks were beginning, and the report’s sponsorship by Qatar, a supporter of the rebels, can lead observers to want to relegate the imagery to no more than another volley in the attempt to claim the higher ground. While the existence of 55,000 photographs showing such barbarity would have previously been more than enough to strike a profound chord in the public conversation, perhaps viewers and governments alike are becoming habituated to such horror on a mass scale. Or perhaps we are now also aware that in the United States alone we regularly take more than 55,000 photographs every 15 seconds.

Fred Ritchin is a professor at NYU and co-director of the Photography & Human Rights program at the Tisch School of the Arts. His newest book, Bending the Frame: Photojournalism, Documentary, and the Citizen, was published by Aperture in 2013.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com