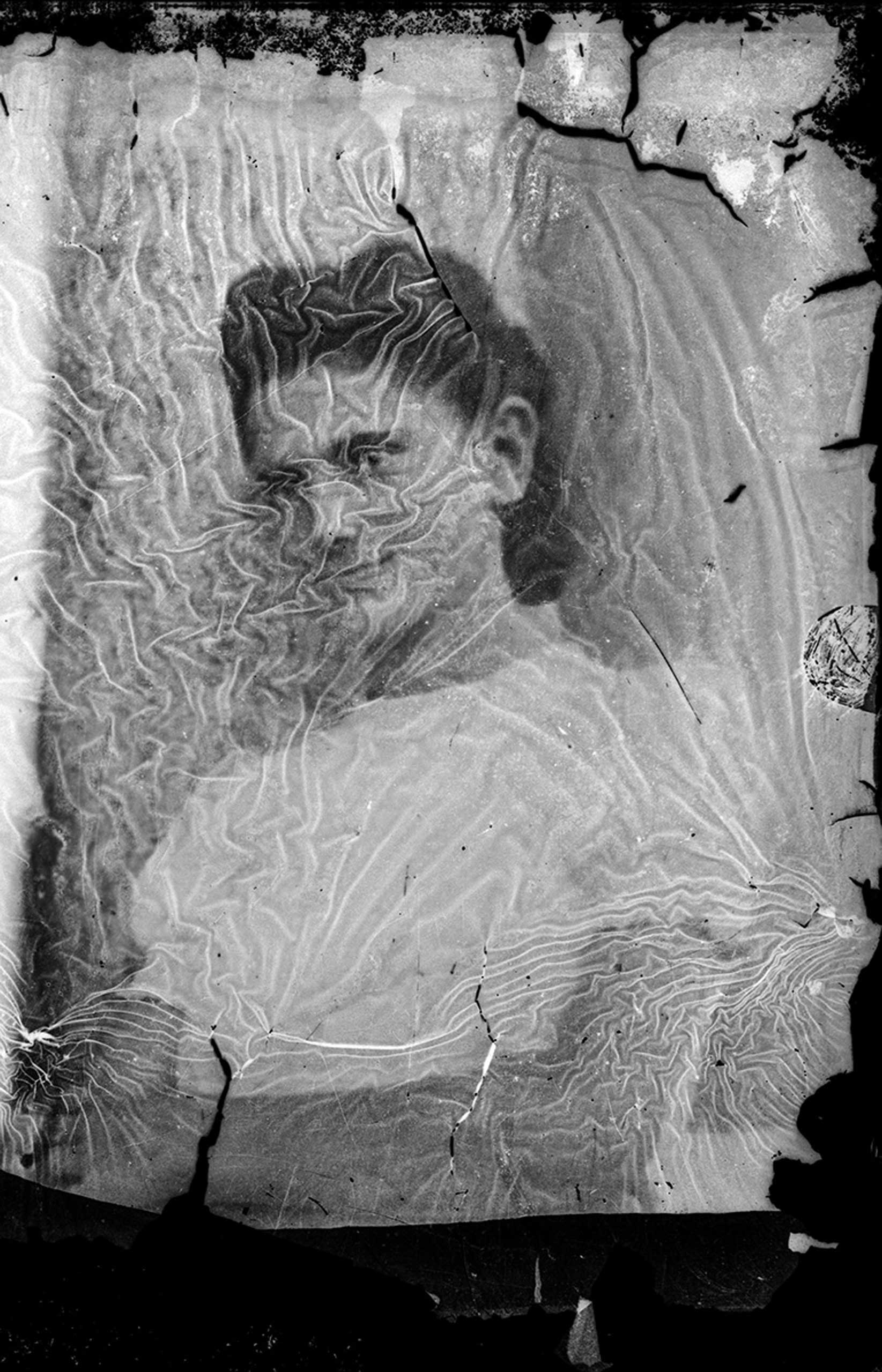

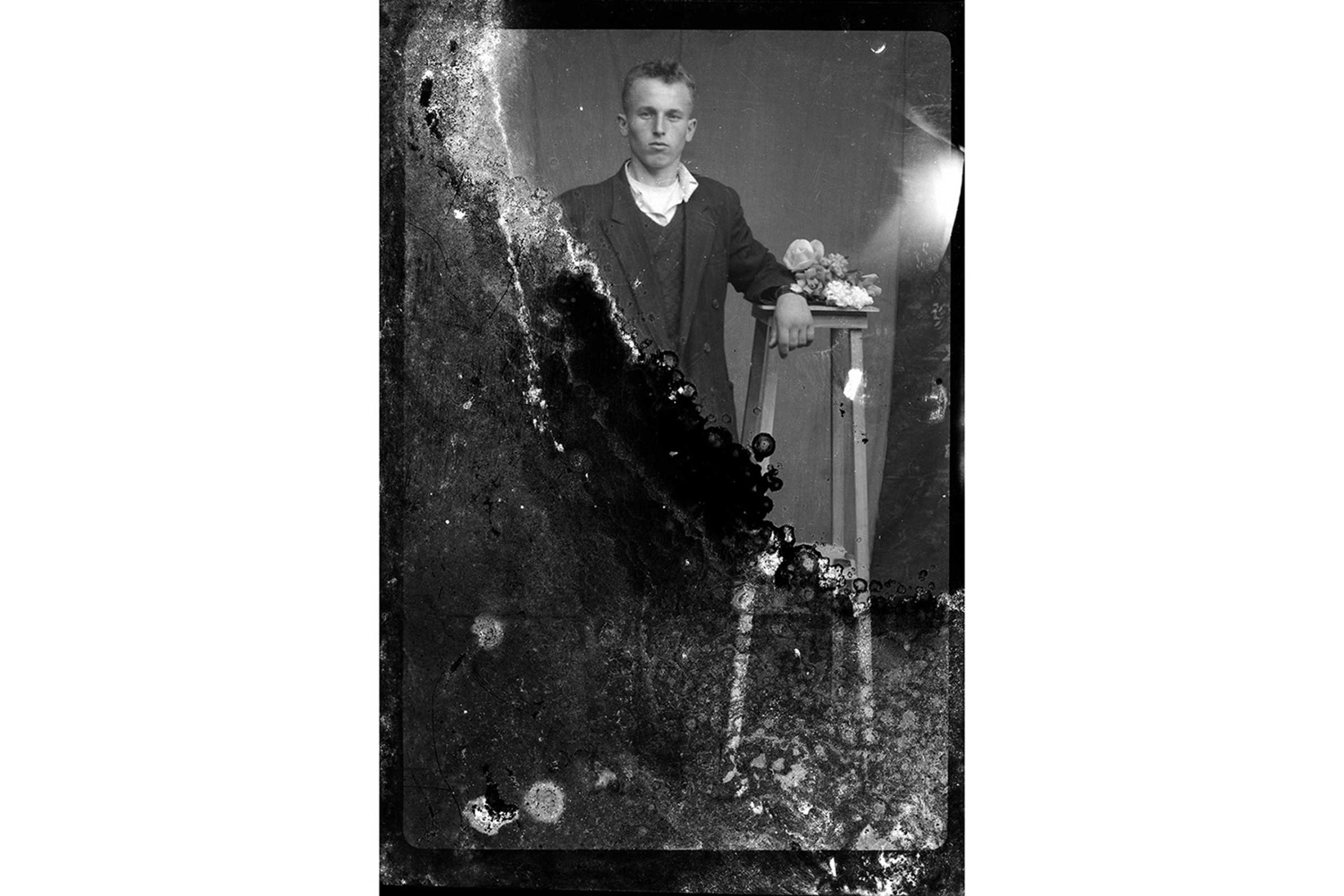

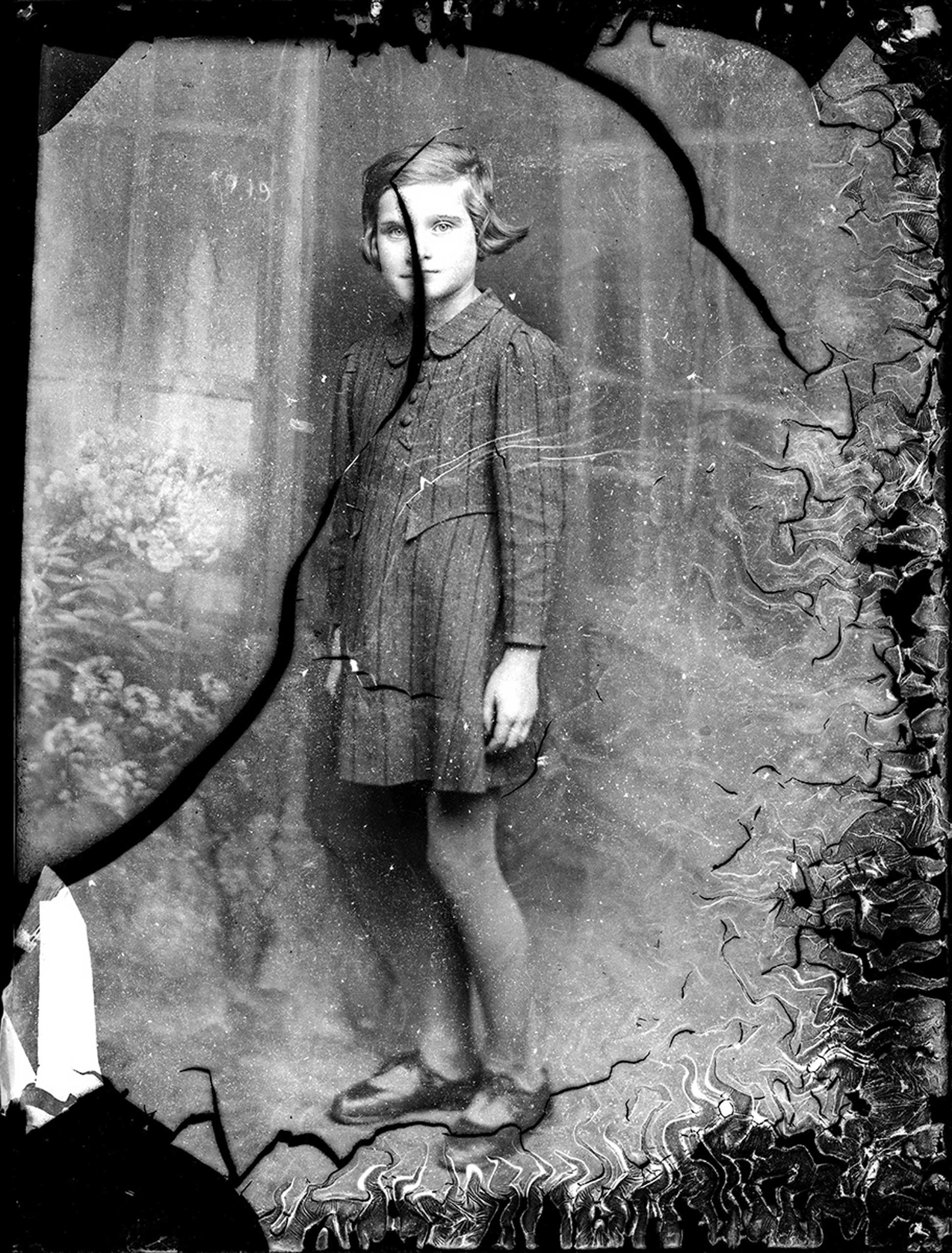

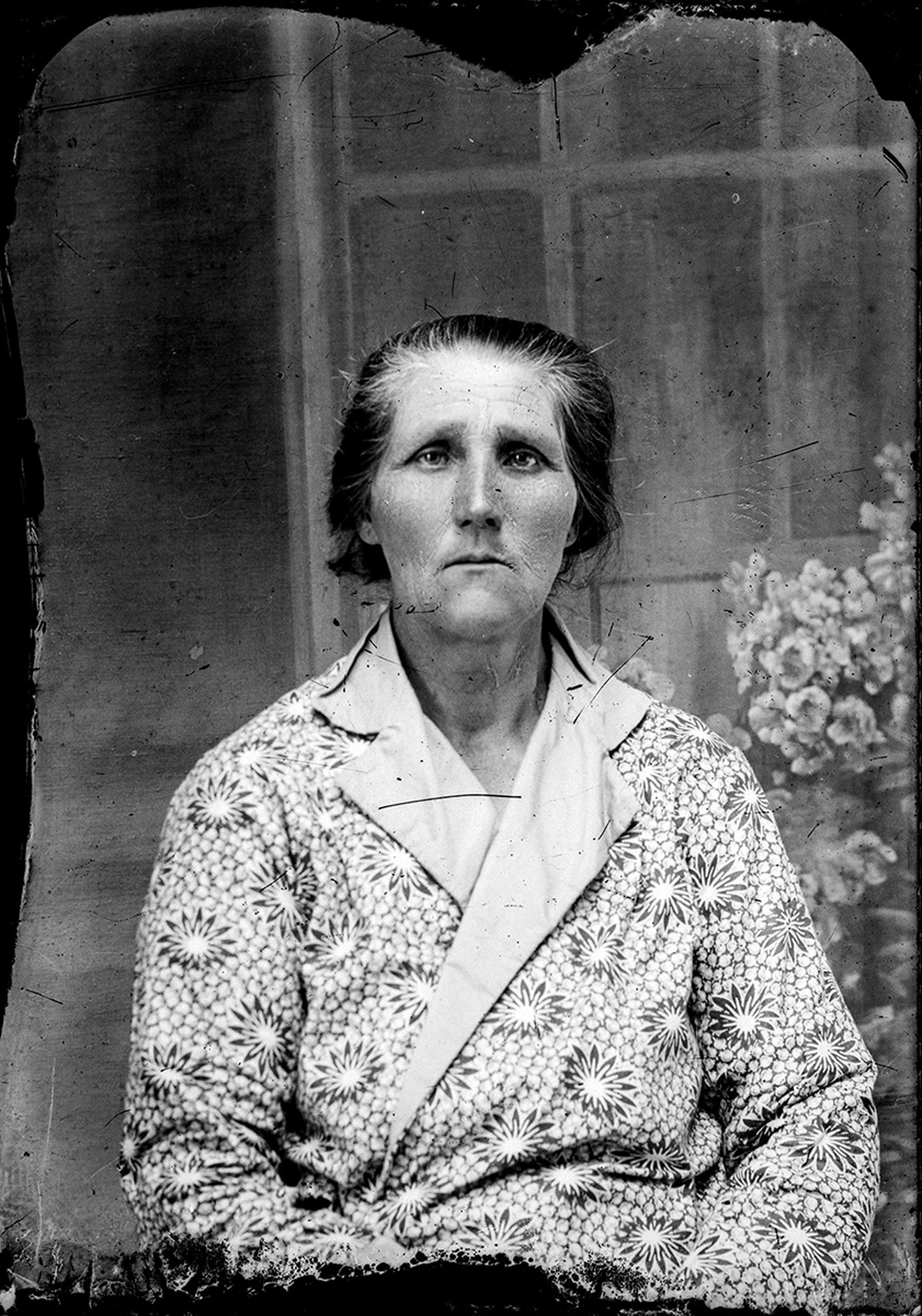

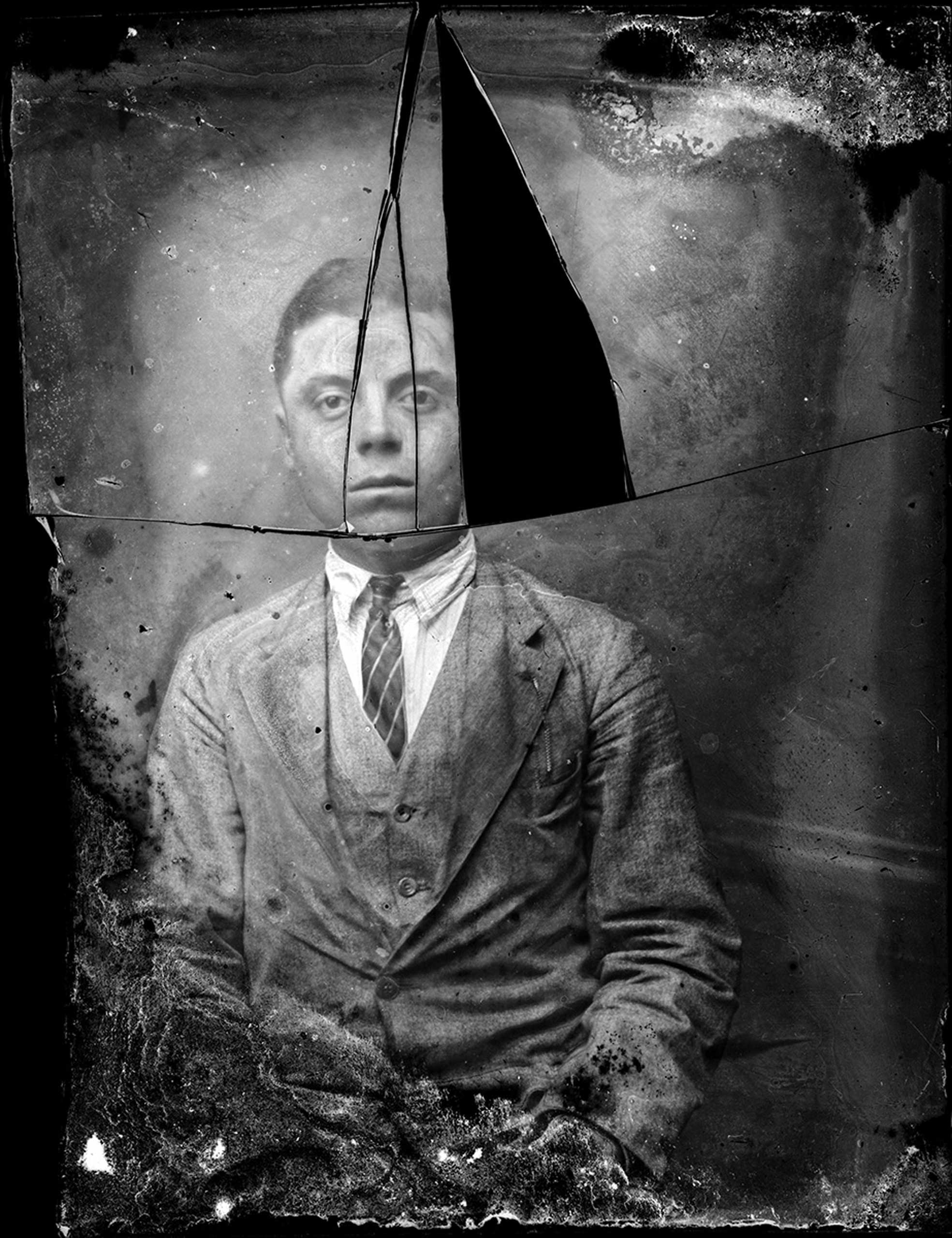

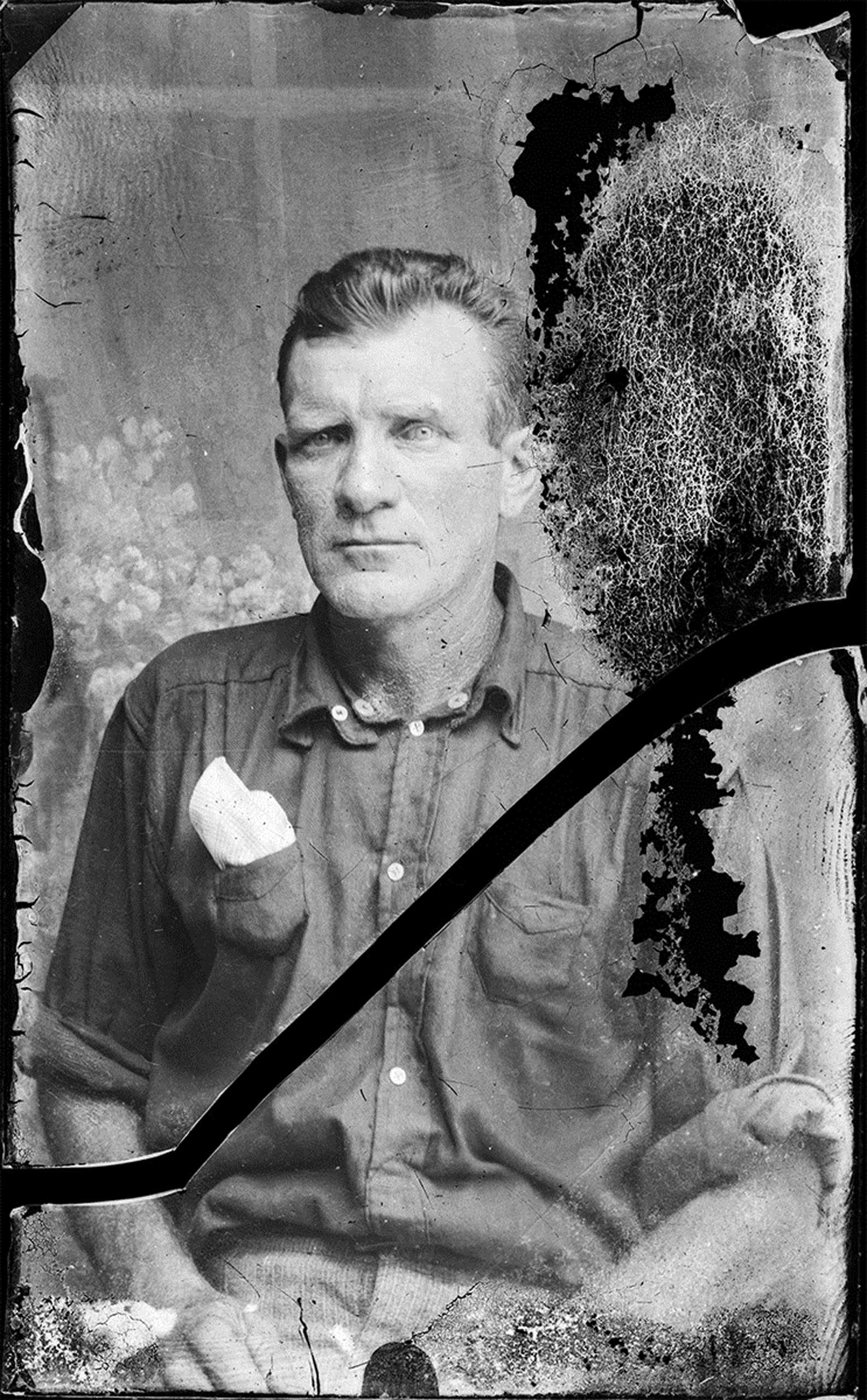

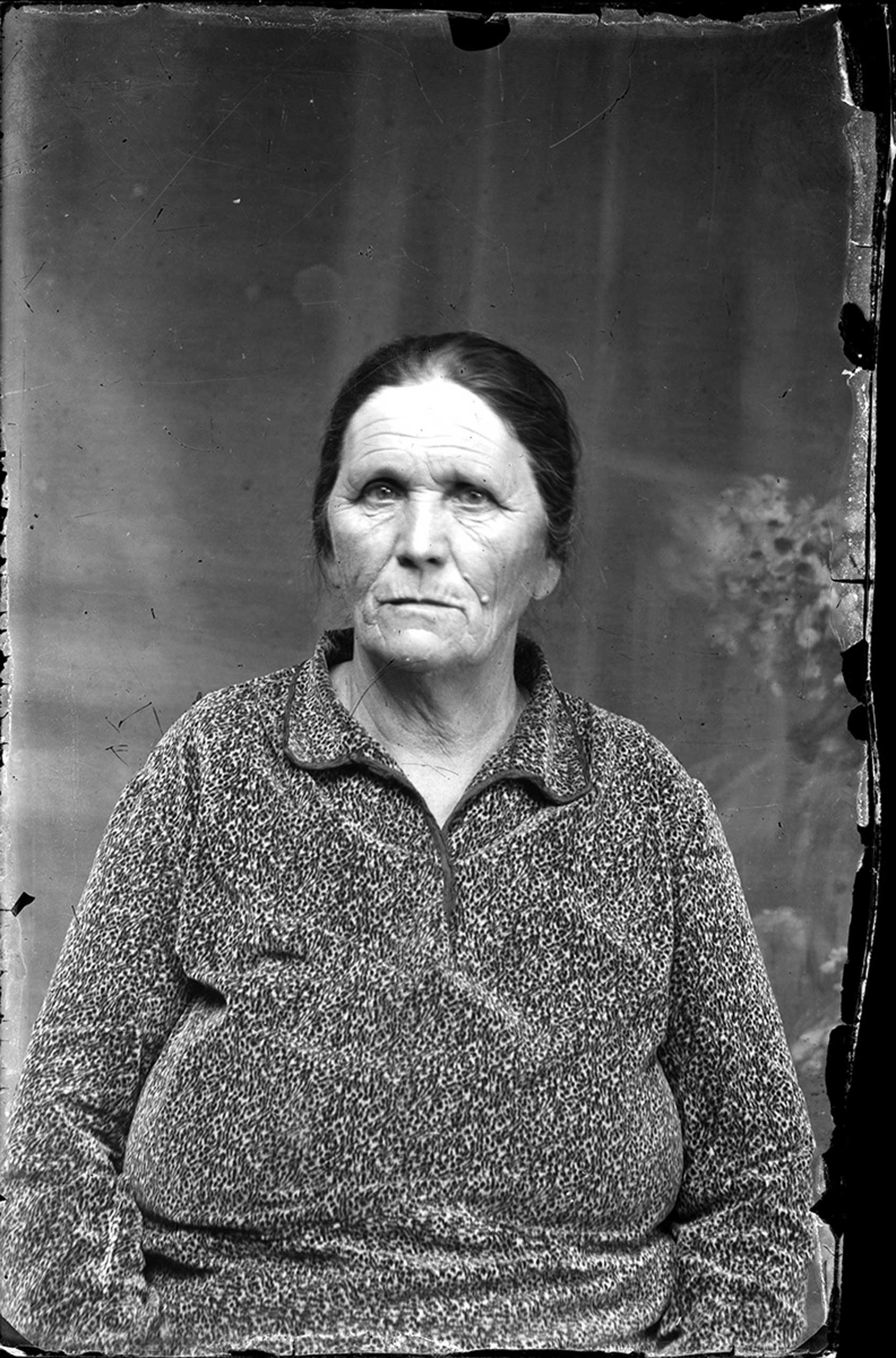

Time has rendered these portraits virtual abstractions. Beyond the psychedelic swirls of their shrinking, pealing emulsion, next to nothing is known about the subjects of the photographs, and very little about the photographer who made them. The greater part of their allure comes not from the information revealed, but from what is obscured and denied to the viewer.

Costica Acsinte was a Romanian army photographer during World War I who, following his discharge, opened a small commercial studio in Slobozia, about 80 miles east of Bucharest. For two decades after the war, he was likely the only professional photographer in the county, and by the time of his death in 1984, he had built an archive of epic, anthropological scope containing upwards of 5,000 glass-plate negatives and several hundred prints.

“Anybody who needed a picture had to come to his studio,” says Cezar Popescu, the one-time lawyer-turned-photographer who for several years has been painstakingly working towards digitizing the entirety of Acsinte’s archive with no institutional or state support.

Popescu, whose father had once worked with Acsinte’s son as a photographer, recognized the work several years ago after a small regional history museum published a few postcards from the archive. The museum acquired the plates — which had been kept in wooden crates open to the elements and even to curious livestock, Popescu says — from Acsinte’s family a few years after his death. The pictures remained mostly untouched until Popescu finally convinced the museum to let him scan them all before they crumbled completely.

“Piece by piece I hope to add as much information as I can,” he says, “but right now my main concern is to get the plates digitized. The degradation is quite rapid. Day after day, I notice another crack [in the emulsion].”

Few of the plates have inscribed dates or captions. Other than occasional military insignia, most bear no indications of when or where they were made or who their subjects are. “I’m not the guy who can tell you if the content of the pictures is important or not,” Popescu adds. “To me it just seems a shame to lose something so irreplaceable.”

As with most abstract work with few or no fixed referents, each encounter with the images feels unique. Popescu hopes someone out there can one day recognize a relative, or notice something of historical or regional significance, in one or more of the works. But their haunting aesthetic quality allows viewers to read into them whatever they want.

Since Acsinte’s death in 1984, there have been no know licensing restrictions on these images. In fact, the entirety of Acsinte’s work is in the public domain, as under Communist rule in Romania creative photography could legally retain copyright for just a few years. The pictures are free for anyone to take and share, edit and interpret, sequence and re-sequence, on a blog, a printed page, a wall, a billboard — anywhere. Find the entire archive available for download via Flickr or follow on Facebook and Twitter. Recognize any faces? Send us a tip at LightBox@TIME.com.

Update: February 2014: The original version of this article had mistakenly referred to Costica Acsinte as “likely the only professional photographer in the country,” rather than “county.”

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based writer, editor and photographer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com