It was easy to be declared a witch in Salem in 1692: All you had to do was deny that witches existed.

After a number of the town’s teenagers began to hallucinate and convulse, bark like dogs and run around on all fours, two magistrates were tasked with rooting out the evildoers behind the bizarre afflictions. The men invented their own methods for detecting witchcraft, according to TIME’s 1949 review of the book The Devil in Massachusetts:

After due deliberation the magistrates declared that a devil’s “teat” or “devil’s mark” on the body of the accused was proof of guilt, that mischief following anger between neighbors was ground for suspicion, and, most important of all, that “the devil could not assume the shape of an innocent person.” This last meant that hallucinations would be accepted not as evidence of the wrought-up condition of the accuser but as proof of the guilt of the accused.

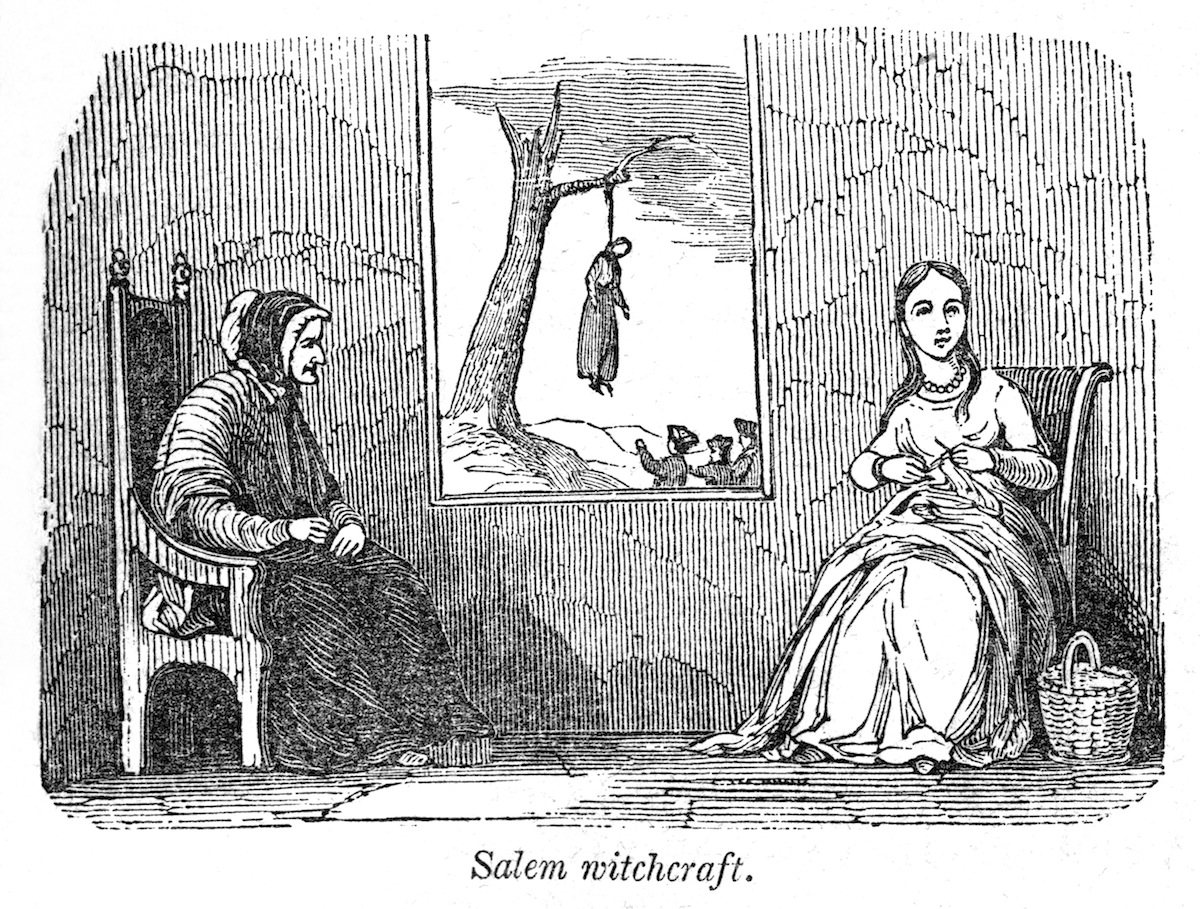

In practice, suspicion fell even more broadly. In the absence of a devil’s mark or neighborly mischief, anyone who stood up to authorities and publicly questioned their actions was likely to be Salem’s next top suspect. Such was the case with Martha Cory, “a hearty matron who had rashly asserted she didn’t believe in witches,” and who appeared soon afterward in a stricken girl’s vision. Since the girl was in church at the time, half the town heard her scream, “Look! There sits Goody Cory on the beam, suckling a yellow bird betwixt her fingers!”

Cory (also spelled Corey) was among the seven women and one man hanged as witches on this day, Sept. 22, in 1692. It was the last round of executions before the tide of public opinion turned and the trials began to subside. They had claimed 20 lives.

Although Cory had urged her examiners not to believe “all that these distracted children say,” according to Charles Upham’s book Salem Witchcraft, the jury was less moved by her words than by the convulsions of her accusers while she spoke. In the midst of the proceedings, one woman threw her shoe at Cory, hitting her “square on the head.”

Cory’s husband Giles, who defended his wife and was therefore labeled a “dreadful wizard,” had been executed three days earlier — pressed to death under a pile of stones. In the backwards justice of the trials, those who confessed were spared, while those who protested their innocence were often killed. Giles Cory, who refused to plead guilty or even to stand trial before a corrupt court, endured the torture of a slow death instead.

Asked for his confession whenever a new layer of stones was added to the pile, he is reported to have answered only, “More weight!”

Read a 1999 story about the rise of Wiccanism in the armed forces: I Saluted a Witch

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com