It might be the end of the line for the U.K. The Scottish vote on independence is happening tomorrow, with millions going to polls to decide whether their country should secede from the union with England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Scots seems almost evenly split on the issue. With the nays saying a withdrawal will jeopardize the country’s ability to use the British Pound and its membership of the E.U., and the yays arguing that the country could better control its own future, free from London rule.

The U.K. already has one international border — where Northern Ireland meets the Republic of Ireland — but Great Britain (the island consisting of just England, Scotland and Wales) hasn’t had one since the act of union joined England (which had already annexed Wales) and Scotland — in 1707.

So what would happen if it did?

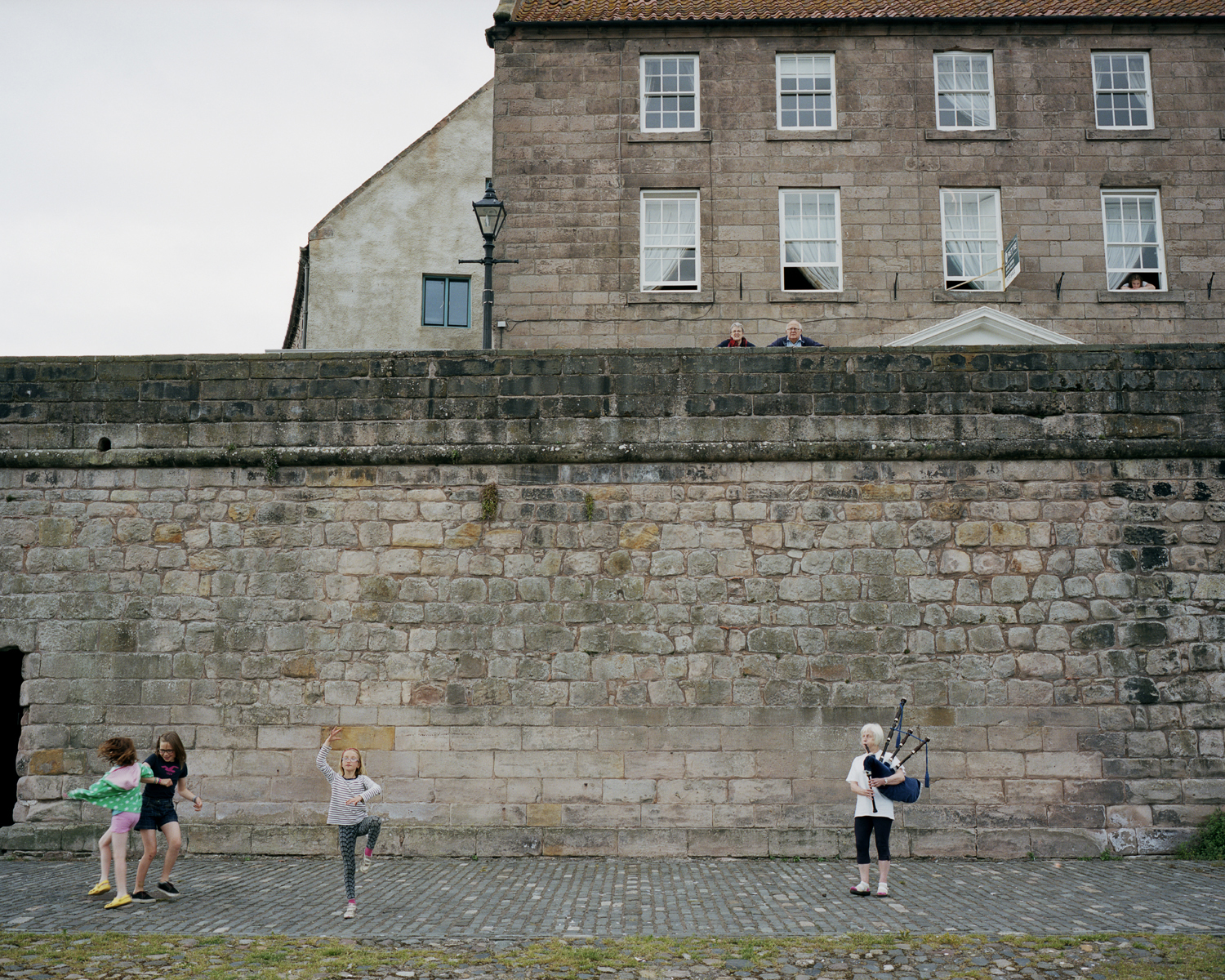

That’s the question Jo Metson Scott explores in her project Borderland, which is loosely pegged to tomorrow’s plebiscite. Fascinated with life in the geographic extremities of Britain, Scott spent months documenting the northernmost parts of England, where towns and parklands skirt the existing Scottish border.

“I wanted to do something on people that were living on a potential [international] border,” she tells TIME. “And how that affects someone’s identity and their culture. Not just looking at the wider political implications, but on the smaller daily activities, too: like how it will affect what hospital they go to.”

To do this, she traveled with writer Sarah Saey (who penned witty prose to accompany the work) to places such as the very Scottish-sounding Berwick-upon-Tweed and Kilder Forest Park, areas that are, in fact, in England. Here Metson Scott photographed locals who do cross-border business on a near-daily basis and whose lives are deeply rooted in both countries – people who live in towns that might seem Scottish to a Londoner but likely pretty English to someone from Aberdeen. But the work, she adds, was in no way meant to act as political commentary – this is straight up documentation of a way of life.

The images that emerge are an intimate look at life in a buffer zone. Here, signifiers of both nations seem to blend: we see rolling green hills, English townspeople sporting kilts and a mist-shrouded rock that could be mistaken for something in the Scottish lowlands, if it didn’t have “England” emblazoned across its front.

“As the border goes from west to east, it starts to veer north,” Metson Scott says. “So the most southern part of Scotland is further south than the northernmost part of England. A lot of the time you would get confused — not sure of what country you are in,” she adds, laughing. “I screeched to a halt when I saw a highland cow in England!”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com