On Thursday, when Scottish voters put their relationship with the U.K. to the ballot, three hundred years of membership in the United Kingdom will be at stake. But those 307 years of togetherness haven’t passed unquestioned. In fact, it was almost exactly 40 years ago that the movement for an independent Scotland reached a similar tipping point.

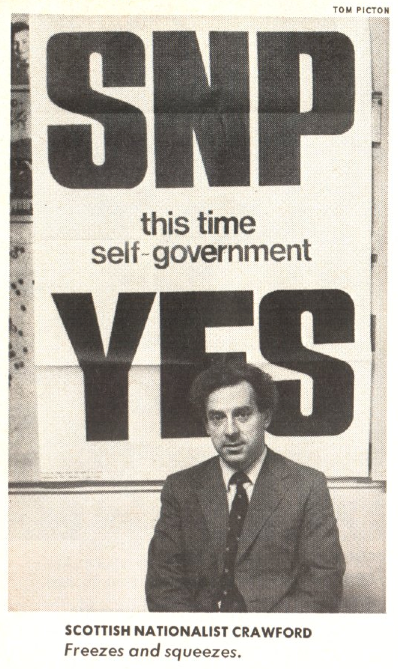

The Scottish National Party had spent nearly half a century as a mere footnote to Scottish history when, in the mid-1970s, it became a force to be reckoned with. In 1974, running on a self-government platform, the party secured 30% of the vote, driven largely by Scottish interest in gaining control over North Sea oil production. “There is no rancor toward England in most cases, no implied violence or even incivility, just a general feeling that she’s a tired old ship that is foundering at sea,” TIME reported on Oct. 28 of that year. Polls at the time found that 17% of Scots wanted complete independence and 85% wanted self-governance without a split. By the end of the following year, Prime Minister Harold Wilson had announced that there could be a vote in Parliament delegating some of its duties to the regional governments in Scotland and Wales.

It took years for that promise to go anywhere, but in 1979 Scotland and Wales voted on “devolution,” that process of delegating authority. Wales rejected the referendum — and, in a surprise, Scotland did too. This despite the fact that polls one month prior to the vote had shown a 2-to-1 preference for devolution. The final count? A mere 33% voted yes.

“Appealing to local pride, the Scottish Nationalists argued that if devolution failed to pass, Scotland would ‘be good for nothing more than to tart up a few British ceremonies.’ But the antidevolution forces, led by the Conservative Party, mounted a late-blooming campaign that focused on an even more basic Scottish instinct: they charged that the cost of home rule would be quickly felt in the form of higher taxes,” TIME reported.

For this week’s vote, a large majority of Scots are expected to turn out to vote, and recent polls have shown that the yes/no votes could be close. But the 1979 vote, over a much less drastic change, was supposed to be a win for devolution. Instead, the status quo won handily. If this week’s vote follows the pattern of the 1970s decision, then a large percentage of the yes votes indicated in early polling will disappear when the decision must be made.

Support for increased Scottish independence has been fairly steady since the ’70s, according to the Scottish Parliament’s own historical records. In fact, that Parliament — which had been dissolved April 28, 1707, in order that a united Parliament of Great Britain could come into session — only exists because of that support. The first meeting of the Scottish Constitutional Convention took place in 1989, and in 1997 the U.K. government published a white paper on the topic of a Scottish Parliament. A referendum for devolution was held in September of that year, and the resulting “yes” vote led to the 1998 passage of the Scotland Bill, which established a Parliament that opened the following year. The powers of the Scottish Parliament, known as “devolved powers,” included education and housing; the “reserved powers” that stayed with the U.K. Parliament included immigration and defense. In 2012, another Scotland Act added — for example, setting a national speed limit — to the list of devolved powers.

The last time Scottish self-governance lost at the polls, TIME posited that the “no” vote wasn’t just a matter of taxes: “Some Scots also began to ponder the fact that devolution might lead to the breakup of the United Kingdom, which none but the most extreme nationalists want.”

Which is, of course, exactly what the Sept. 18 referendum — no matter of mere devolution — will determine. It’s no longer such an extreme-sounding prospect. In fact, Alex Salmond, the First Minister of Scotland, told TIME in 2011 that he believes Scotland will join the list of nations that used to live under English rule sooner or later.

Read the full interview with Alex Salmond here: Is Scotland’s Independence from the U.K. Inevitable?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com