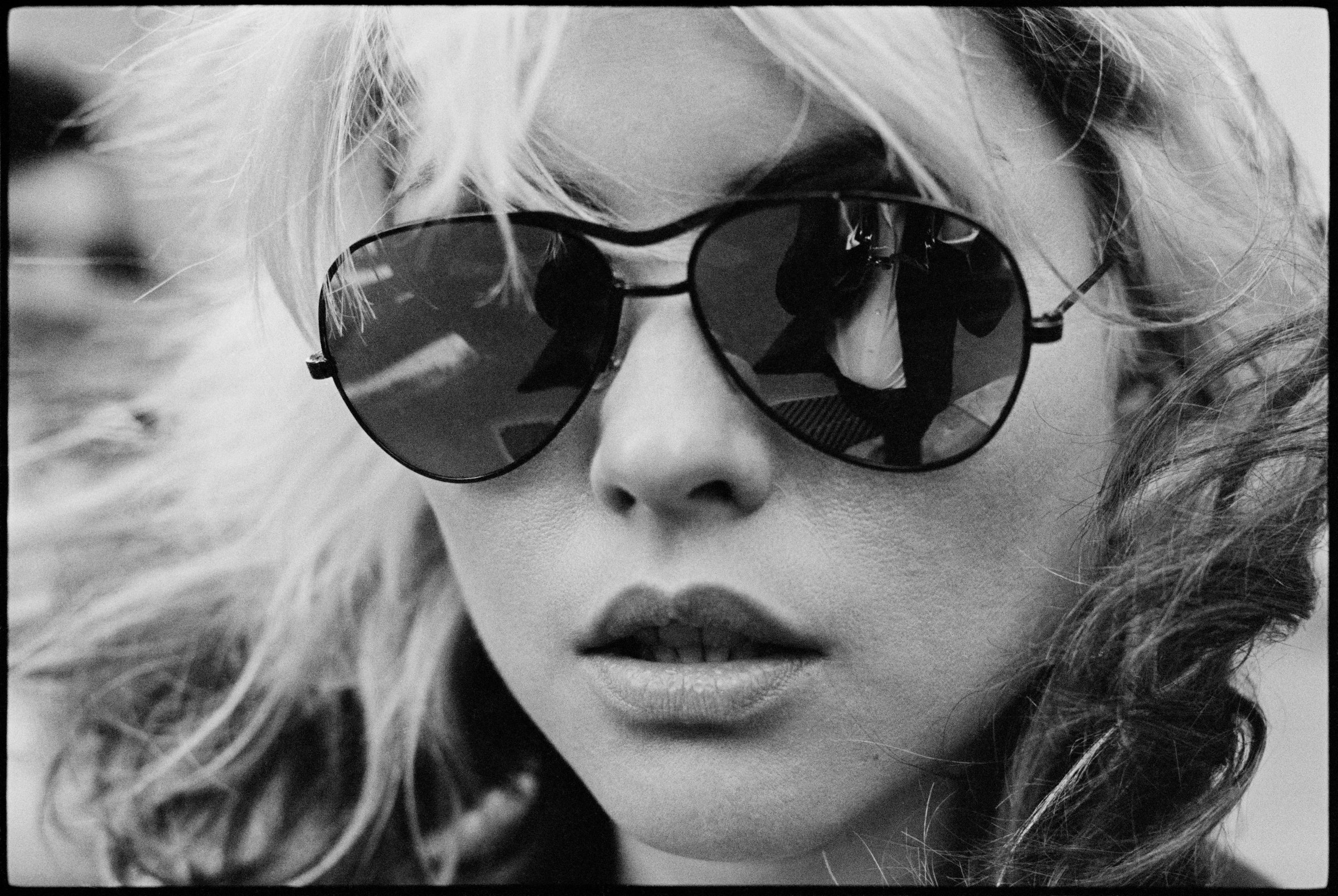

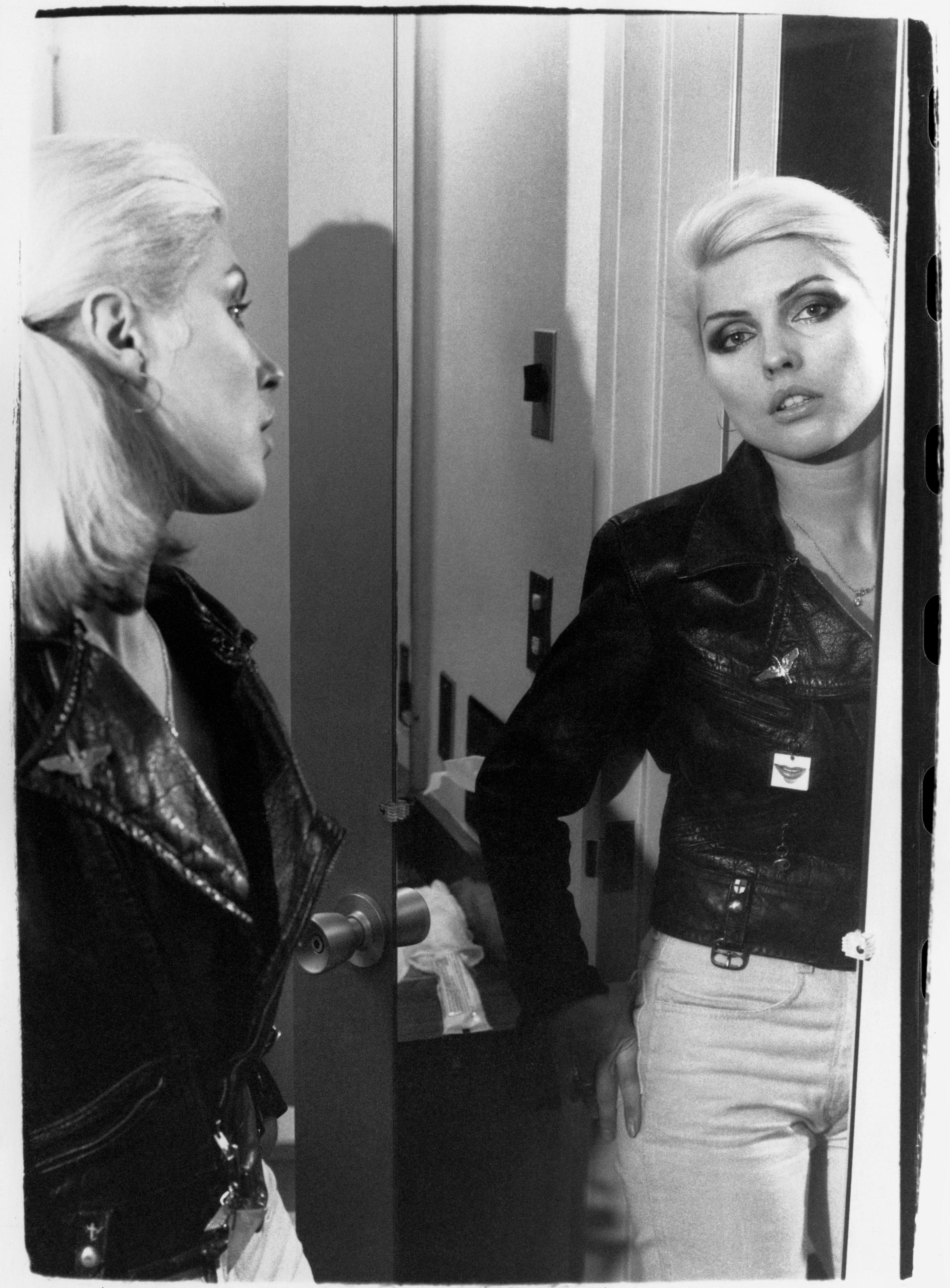

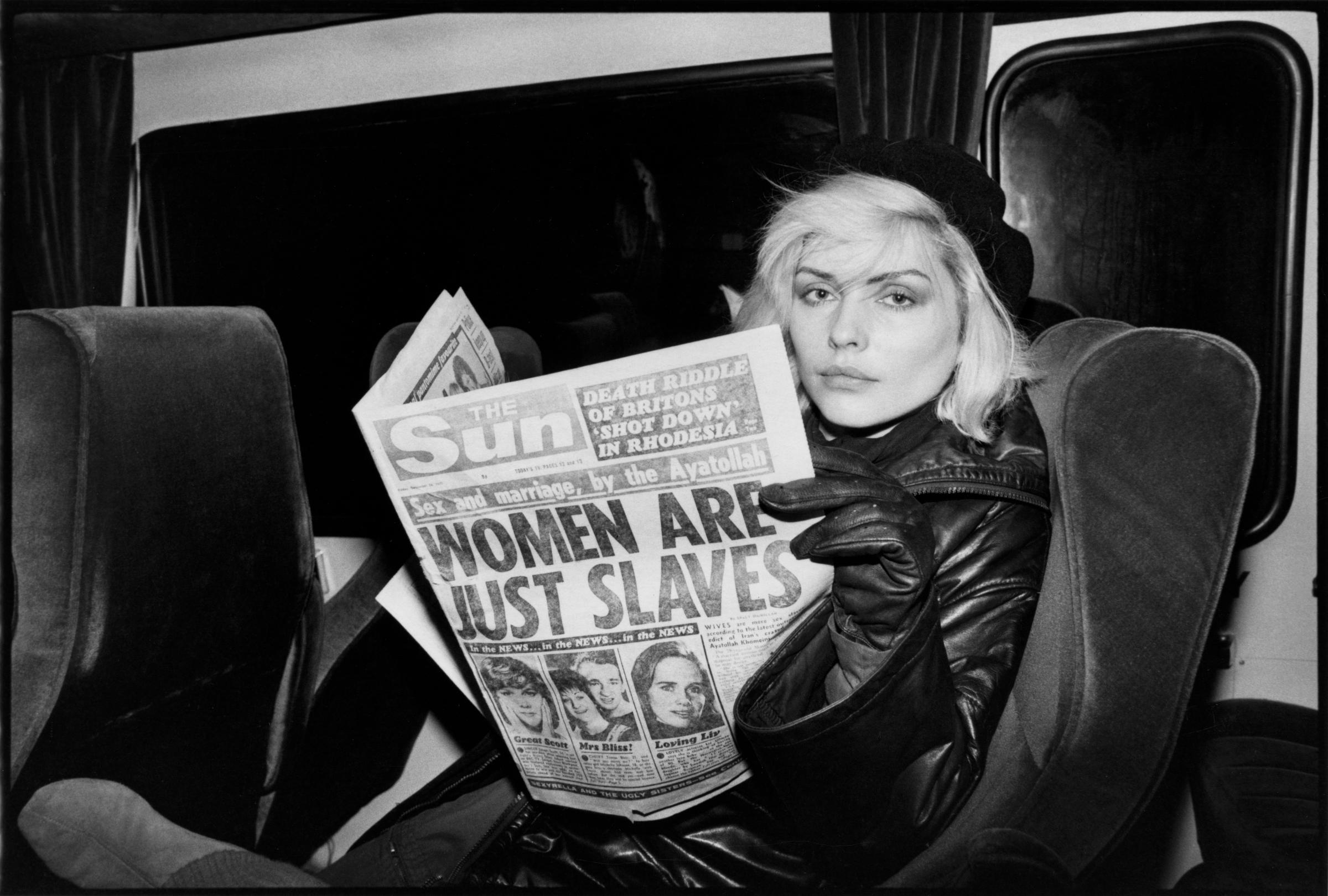

In 1974, New York City was the home to a potent burgeoning punk and new wave scene. Blondie’s Chris Stein was there for all of it: his guitar in one hand, his camera in the other.

Since their 1978 breakthrough album Parallel Lines, and its ethereal disco-tinged hit “Heart of Glass,” Blondie has been a genre-defying musical force, easily blending disco, punk, pop and new wave through the ‘80s, ’90s and aughts — and even today, with their most recent album, Ghosts of Download. As Blondie celebrates its 40th anniversary, Stein is releasing his first book of photographs, Chris Stein/Negative: Me, Blondie, and the Advent of Punk, which documents his life on stage, on the road and at home, including portraits of his friends who made the downtown scene: Iggy Pop, David Bowie, Andy Warhol, Joan Jett, Jean Michael Basquiat and many more.

To help mark the occasion of the anniversary and the book release, TIME talked to Stein and the band’s unforgettable lead singer, Debbie Harry, about being Blondie, nostalgia, hanging with Grandmaster Flash, and the evolution of New York City.

TIME: How do you guys keep that going after 40 years?

Debbie Harry: Lots of vitamins. I’m just kidding.

Chris Stein: I take lots of vitamins every day. I take tons of vitamins. You take some vitamins.

DH: I take lots of vitamins too, but I don’t think that’s what keeps us going. Do you?

CS: No. There’s some willpower involved, I suppose, too.

There are very few bands who have managed to last as long as you.

CS: Big question is: who’s going to be around to listen to us now or in 30-40 years, you know?

Right. Who do you think has a good shot at it?

DH: It’s hard to tell.

CS: I don’t know. I think longevity has to do with biology, almost. Everything moves so slowly, it has to, I think. There’s so much turnover now, there’s no time for longevity.

DH: Yeah, definitely. I think there [are] musicians, like different guys from Muse and Arcade Fire and stuff like that.

Did you say Muse?

DH: Muse.

I hadn’t really thought of Muse lasting for 40 years. But I guess they could.

DH: I don’t mean as a unit — I mean different people from different groups.

CS: Like Zach [Condon] from Beirut. I mean that guy’s going to be a musician his whole life. No matter what he does, I’m sure that he’ll be doing stuff.

Given that you started out with the Talking Heads, who aren’t really talking anymore, and then we just lost the last of the Ramones, it’s pretty impressive that you guys are now celebrating your 40th anniversary.

CS: The Ramones’ first album just went gold recently after 35 years. It’s ironic to all of us.

DH: Yeah, it is.

Was losing the last of the Ramones kind of hard for you?

CS: They’re all such nice guys. They’re all such sweet guys. They were weird, but they were all really nice, genuine people.

Thinking back to when Blondie first started, are there other bands that you’re surprised didn’t make it bigger?

DH: I think that in today’s world, Alan Vega’s Suicide would have made a much bigger impression had they come out in the ’80s. They had a really modern approach.

CS: By the ’80s, there were other people testing the waters that those guys were doing. Those guys, they were just completely unique.

DH: That’s what I meant. If they had became famous at the very beginning of that, they would’ve gone a lot further.

What do you think it is that makes your songs so appealing to so many generations?

CS: They’re cheerful. You know, I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. We tap into a lot of things from musical history when making the songs. They’re based on a lot of stuff that’s come before us so maybe that’s… You know, we got one review recently from one of those Canadian festivals. It [was] a really great glowing review, and she said that the band almost sounds psychedelic in its presentation, which I thought was great because I always think that, but I never really see it in print. There’s a lot of influences from the ’60s, ’70s, [and] later music in there, so I think maybe that clicks with people.

Your most recent album had a lot of different influences, from heavily electronic stuff to some Latin flairs.

CS: I’ve been deep into this Latin stuff for the last four years or so. I really like what goes on in the modern Latin scene. I hear that the official figures are that one-sixth of the population of the U.S. is Latino now, and it’s probably closer to a fifth, but maybe even a quarter. But it doesn’t cross over because it’s all Spanish-language. More and more, I’m hearing those influences coming into the mainstream now.

Speaking of incorporating influences, every time I hear “Rapture,” I’m really struck by the fact that you basically incorporated rap into a song, before people really knew what rap was. How did that song come about?

CS: Just from getting really excited by seeing our first glimpses of the rap movement in New York, uptown. It was already really up and running by 1977 when we first started playing stuff. It hadn’t gotten out of uptown New York at that time. It was still a very closed thing.

DH: I think there was a little sort of pocket of it somewhere in New Jersey, perhaps Newark.

CS: It was probably all over the country even, too, probably other cities had their own scenes, but it just hadn’t crossed over. There hadn’t been anything on the radio at that point.

DH: No, there definitely was nothing in the open market. It was all sort of ghetto.

CS: Guys were passing out singles and stuff.

DH: Yeah, I mean, Sugar Hill was doing a lot of singles then.

Did you see rap shows back in the day? Did you hang out with any of the early rappers?

CS: We met Flash a bunch of times. Yeah, he was great. I sometimes see Rodney C from the Funky Four, a few people. I got involved with WildStyle, which Charlie Ahearn did — that movie in the early ’80s.

You’ve been playing some of your songs, like “Heart of Glass,” for 40 years. How do you make it fresh, and how do you still make it fun for yourselves to play?

CS: Well, the live arrangement of that is quite different than the record, and that took a couple of years to develop to where it is now. It’s all different things. The audience reaction has a lot to do with the emotional content.

DH: That’s what I was going to say. When that little drum machine thing comes on in the beginning, the audience hears the first few bars of that, there’s the response, and I think that sort of cheers us on, you know?

CS: I always say there’s a tribal element in a rock concert. There’s a real back-and-forth thing that goes on between the audience and the performers.

When you started this band, did you expect to still be doing it in 40 years? Did you expect to be doing it in 10 years?

DH: No. I don’t think that we had any criteria for that.

CS: Everybody was pretty much in the moment, then, and I don’t think anyone thought much about the future. I don’t think people in their 20s and early 30s think much about the future, anyway.

DH: The vagaries of the industry and show business itself would not lead one to conclude a lengthy career — because things change. It’s just one of those things. Popularities come and go. The tragedy of it is that somebody like Robin Williams should suffer from that, and be driven to commit suicide. If ever there was an untimely, unfair death, it was him. I mean he entertained people so well for so many years, and then to have a TV show not make it and to have financial problems and to be so affected by it — it’s a real tragedy.

It is. Have you guys felt affected by fame in that way?

DH: We go through ups and downs. Getting the band back together was Chris’ idea. Fortunately we got hooked up with a really smart businessman and manager, and we were able to do it. But in many cases bands have a lot to overcome, business being what it is.

Having been in the industry for so long, what are some of the biggest changes that you’ve seen from when you started to now?

CS: It’s just the obvious stuff. The record sales and touring have reversed their position. Whereas the tour, the show used to be advertising for the record, and now that’s reversed. The record is just a collectible at this point. It’s a piece of merchandise. It doesn’t mean what it used to.

DH: Well, it doesn’t for the majority of bands or artists. There’s a relatively small percentage of working bands [for whom] record sales or CD sales, or whatever it is, is of major importance.

CS: Now downloads.

DH: Only the top 5%.

CS: It’s not even 5%. It’s a fraction of 1%. It’s the same as the actors who make X millions of dollars a year compared to all the other actors. It’s the same deal.

DH: Yeah.

Just listening to you two talk is so funny, because you’ve obviously known each other for so long and you have no qualms about talking over each other. How has your relationship changed over the years?

CS: I don’t know. [laughs] I know aspects of it. We don’t live in the same place — that aspect has changed.

DH: We’re not a couple anymore, so we have separate lives.

CS: We don’t live in the same house.

DH: We still have an easy language for working together. We like each other… I think.

CS: Yeah, she’s great. She’s one of my best friends. That’s the way it is.

Chris, you had obviously had your camera with you a lot back in the day. Were you trying to document a scene, or were you just a big fan of photography?

CS: I just like photography. I don’t know if I consciously thought about documenting what was going on. I just liked capturing the images and the time travel involved in photography.

What do you mean by time travel?

CS: When you see a photograph of something, a historic moment or something in the past, it clearly puts you there, in a way. Same with films. I don’t know how conscious my efforts were, but I worked on this book all year, and we’ll see what happens with that.

DH: I know from all these years of being with Chris that he does have a real appreciation… He’s always been — the guy who’s in the museum who’s documenting all the things…

CS: A curator?

DH: Yeah, Chris has always had the mentality of a curator. That’s part of his personality. I don’t think of it as being conscious or unconscious. It’s automatic.

Marking the band’s 40th anniversary and having worked on this book all year, are you guys feeling nostalgic about the past?

CS: With everybody dying and with the big change in the culture when we went through, this rough-edged situation to this fucking crazy rampant consumerism that we’re in now, you know — I was walking around in the Lower East Side, and there used to be freaks and weirdos just wandering around all over the place, and now it’s like, all the hipsters look like they just bought their outfits at the Gap. There’s a kind of uniformity there that I didn’t used to see. But there’s also a lot of great stuff that’s happening now. I think that human nature being what it is, the connectivity that everyone is experiencing — maybe it hit the human race too quickly. Maybe if it had happened in 10 years or whatever, it might have been preferable. Because everybody is connected to each other, but it seems to be making for more isolation. Because when you see a subway car full of people all staring at their phones, there’s a lack of connection.

And Debbie?

DH: It’s one of those situations where, in music, we always say that the pendulum swings back and forth, and I definitely feel that there’s going to be a reversal in this regard. The pendulum will swing back another way. And I’d be very curious to see whether it’s a direct arc, or whether it veers off to one side, or perhaps just several different angles, but I do think that there’s going to be some kind of — I wouldn’t say a backlash, but I would just say it’s going to be an alternative expression or reaction.

CS: I’ve been seeing that for the last couple of days, Gene Simmons is all over the Internet saying, “Rock is finally dead.” But then at the same time, we were friends with this band called The Stripes from the UK — they’re from Ireland actually, right?

DH: I don’t know about that for sure.

CS: They’re from the UK, anyway. They’re these little kids, and they are just awesome, and they’re doing old school blues-rock and pub rock. And if that’s any image of a trend that’s coming up, like Debbie says, it may go swinging the other way. Minimalism.

I spoke with him when Kiss was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and he was very vocal about the fact that he didn’t think Blondie belonged in there.

CS: Whatever. What about Bob Marley?

DH: Oh dear. That’s so strange. He didn’t think Blondie should be there?

No, he thought you guys were “disco.”

DH: I mean, what about Madonna, for God’s sake?

CS: I can sum this up. I’m sure Gene Simmons thinks the only one who should be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame is guess who? Okay.

Did you guys ever have backup plans if your band didn’t work out?

CS: I watch so many cop shows now on TV. I really love True Detective. I keep thinking, I wish I’d been in the police. When I was 20 years old, it never would’ve dawned on me as a reality, really.

DH: I don’t really have a backup plan, but I was always attracted to being an actor of some sort, or a performer. God knows, maybe I would’ve joined the circus. I probably would have had to clean up after the elephants or something. Just kidding. At first coming out of school, I thought I wanted to be a painter. So I did gravitate towards that world for a while.

How do you feel walking down Bowery now and seeing that CBGB — a venue you were closely affiliated with — is now a John Varvatos store?

CS: Better that than a bank is all I’ve ever said.

DH: When we found ourselves going on the road for months at a time, we would come back, and it always seemed like something was gone and had become something else. And I think that kind of quick changeover really happens in New York City, probably in other major cities as well, but especially in New York. Things really do change quickly, and it’s always a shock. You say, “Oh my God, that place used to be here, and that was such a great place,’ and it’s become a laundromat or something. It’s inevitable that that stuff changes, but it just seems now that the overall complexion of the city is so middle-class and upwardly mobile. It’s dull.

CS: What I always say is, all the conversations I have now with people in New York turn to real estate, and that just never happened in the ’70s. Nobody was talking about how much it costs to live wherever it was in the ’70s.

Can you see yourselves doing this in another 40 years? 20 years? 10 years?

CS: 50, yeah, I hope so. I’m going to get my hormones injected or something.

In celebration of Blondie’s 40th Anniversary and Chris Stein’s photo book, Chris Stein/Negative: Me, Blondie, and the Advent of Punk, gallerist Jeffrey Deitch curated an exhibition of works by Bob Gruen, Annie Leibovitz, Roberta Bayley, Mick Rock, Robert Mapplethorpe, Bobby Grossman, David Godlis, and Stein. The exhibit is free and open to the public from Tuesday, September 23rd through Monday, September 29th, 1-8pm daily at the Chelsea Hotel Storefront Gallery (222 West 23rd Street).

MORE: One Direction Announces New Album Four, Out November 17

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com