You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

Four days before Oscar Pistorius shot her in the elbow, hip and head through the bathroom door at his home in Pretoria, Reeva Steenkamp tweeted a message about violence against women in South Africa. “I woke up in a happy safe home this morning,” the 29-year-old wrote. “Not everyone did. Speak out against the rape of individuals.” As Valentine’s Day broke with the news that the 26-year-old who became a global icon in 2012 by running in both the Paralympics and the Olympics had killed his girlfriend, Steenkamp’s words–repeated around the world–only added to the sense of improbability. I checked Steenkamp’s words on Twitter. Then I found myself scrolling back through her life in 140-character snippets.

Steenkamp–who described herself on Twitter as “SA Model, Cover Girl, Tropika Island of Treasure Celeb Contestant, Law Graduate, Child of God”–tweeted a lot. She loved her friends! She loved red-carpet events and award ceremonies and sponsored parties! She loved her modeling agency and new skin creams and the people who fixed her hair!

Above all, Steenkamp really loved her favorite people. And from New Year’s Day to Jan. 7 she posted regularly from a vacation she was taking in and around the city where she was born, Cape Town, with a few friends and the man she called “my boo,” who on Twitter goes by @OscarPistorius. On Jan. 3 she posted a picture of the sunrise taken from the balcony of the $680-a-night presidential suite at a spa hotel in Hermanus, 90 minutes southeast of Cape Town. Later that day she tweeted, “The chauffeurs in Cape Town hey. Nice!” and attached a picture of Pistorius driving an Aston Martin. On Jan. 4, name-checking Pistorius, her best friend, a private banker and a luxury-car importer who was sourcing a McLaren sports car for Pistorius, she tweeted about a lunch the five were sharing at Cape Town’s newest hip hangout. “Shimmy Beach Club!” she wrote. “Tooooo much food!!! Amazing holiday :)”

Steenkamp had been dating Pistorius only since November. However brief their life together, her tweets reveal the glamorous life of the white South African elite. In many ways, the end of apartheid 19 years ago, and the crippling sanctions that died with it, made their lives better. Incomes rose, guilt fell. But beyond the painful irony of a woman killed by gunshots having tweeted about violence against women, there was also the killer’s defense: that Steenkamp was the tragic victim of a racially splintered society in which fear and distrust are so pervasive that citizens shoot first and ask questions later. And then there was the murder scene itself, a locked bathroom within a fortified mansion in an elite enclave surrounded by barbed wire, in a country where more than half the population earns less than $65 a month and killings are now so common that they reach the highest echelons of society and celebrity. Why is gun violence so prevalent in South Africa? Why is violence against women so common?

Was this homicide?

Why did Oscar kill Reeva?

To understand pistorius and Steenkamp, to understand South Africa, it helps to know the place where the couple chose to spend their holiday. Cape Town has arguably the most beautiful geographical feature of any city in the world: Table Mountain, a kilometer-high, almost perfectly flat block of 300 million-year-old sandstone and granite that changes from gray to blue to black in the golden light that bathes the bottom of the world. From Table Mountain, the city radiates out in easy scatterings across the olive, woody slopes as they plunge into the sea. Its central neighborhoods are a sybarite’s paradise of open-fronted cafés and pioneering gastronomy, forest walks and vineyards. Commuters strap surfboards to their cars to catch a wave on the way home. The business of the place is media: fashion magazines, art studios, p.r., advertising, movies and TV. Charlize Theron and Tom Hardy just wrapped the new Mad Max movie. Action-movie director Michael Bay is shooting Black Sails, a TV prequel to Treasure Island.

But while Cape Town’s center accounts for half its footprint, it is home to only a fraction of its population. About 2 million of Cape Town’s 3.5 million people live to the east in tin and wood shacks and social housing built on the collection of estuary dunes and baking sand flats called the Cape Flats. Most of those Capetonians are black. Class in Cape Town is demarcated by altitude: the farther you are from the mountain, the lower, poorer and blacker you are. Cape Town’s beautiful, affluent center is merely the salubrious end of the wide spectrum that describes South Africa’s culture and its defining national trait: aside from the Seychelles, the Comoros Islands and Namibia, South Africa is the most inequitable country on earth.

This stark gradation helps explain South Africa’s raging violent crime (and why, contrary to legend, Cape Town actually has a higher murder rate than Johannesburg). In 2011 the U.N. Office for Drugs and Crime found that South Africa had the 10th highest murder rate in the world. Rape is endemic. Two separate surveys of the rural Eastern Cape found that 27.6% of men admitted to being rapists and 46.3% of victims were under 16, 22.9% under 11 and 9.4% under 6–figures that accorded with the high proportion of attacks that occurred within families.

But what really distinguishes South Africa from its peers in this league of violence is not how the violence rises with inequality nor its sexual nature–both typical of places with high crime–but its pervasiveness and persistence. With the exception of Venezuela, all the other top 10 violent countries are small African, Central American or Caribbean states whose populations tend to be bound together in close physical proximity, creating tight knots of violence. South Africa, on the other hand, knows crime as a vast stretch of lawlessness covering an area twice the size of France or Texas. And it has been that way almost as long as anyone can remember.

In 1976, first Soweto, then all of South Africa’s poor black townships, rose up against apartheid in a tide of insurrection and protest. To this day, large areas of the country remain no-go areas for the police. In his 2008 book Thin Blue, for which he spent 350 hours on patrol with South Africa’s police, Jonny Steinberg describes the relationship between police and criminals as part “negotiated settlement,” part “tightly choreographed” street theater in which criminals make a show of running away and officers halfheartedly pursue them. His thesis is that “the consent of citizens to be policed is a precondition of policing.” And in South Africa for two generations now, that consent has been lacking.

Why does no one trust the state? FOR blacks, it’s partly because of South Africa’s historical legacy. And for all South Africans, but particularly for whites, it’s partly because the ruling African National Congress (ANC) is tarred by corruption and criminality. Scandals involving government ministers seem like a weekly occurrence. About a tenth of South Africa’s annual GDP–as much as $50 billion–is estimated to be lost to graft and crime. The past two national police chiefs were sacked for corruption. In the southeastern city of Durban last year, all 30 members of an elite police organized-crime unit were suspended, accused of more than 116 offenses, including theft, racketeering and 28 murders. The initial lead investigator in Pistorius’ case, Detective Warrant Officer Hilton Botha, was removed after it emerged that he faced trial on seven counts of attempted murder. Most damning of all, the ANC’s self-enrichment has helped widen the inequality that first propelled it to power. The result of this dismal record is that while murder rates are down from their peak, the resentment and violence continue.

Unable to rely on the state, South Africans are forced to cope with crime essentially on their own–and over time, that has shaped the nation. Policing is largely a private concern. In 2011, South Africa’s private security industry employed 411,000 people, more than double the number of police officers. In the townships, vigilante beatings and killings are the norm.

The ultimate example of this private crime control is the security estate. The ancestors of the white Afrikaners, 19th century Dutch settlers, had their own response to overwhelming danger: circling their wagons in an impenetrable laager. The most celebrated laager was at the Battle of Blood River in 1838, in which 470 Dutchmen killed 3,000 Zulu warriors while sustaining light wounds to just three of their own. The security estate–a walled-off cluster of houses protected by razor wire, electric fences, motion detectors and guards–is the 21st century laager. Its purpose is the same: separation from what Afrikaners call the swart gevaar or “black threat.” The security estate is a private, individual, exclusive solution to that fear. And Silver Woods in Pretoria, where Pistorius lives behind electrified 8-ft.-high (2.5 m) security walls watched over by the estate’s dedicated security force, is one of the most exclusive guarded communities in the country.

For all its defenses, it failed to keep violence at bay. By Pistorius’ account, his fear of an intruder, the fear that keeps the people of South Africa apart still, caused the man so many saw as a unifying figure to shoot his girlfriend dead.

If South Africa reveals its reality through crime, it articulates its dreams through sports. When in 1995–a jittery year after the end of apartheid–South Africa’s first black President, Nelson Mandela, adopted the Afrikaner game, rugby, and cheered the national team on to a World Cup win, he was judged to have held the country together. In 2010 his successors in the ANC delivered the message that Africa was the world’s newest emerging market and open for business through the faultless staging of a soccer World Cup.

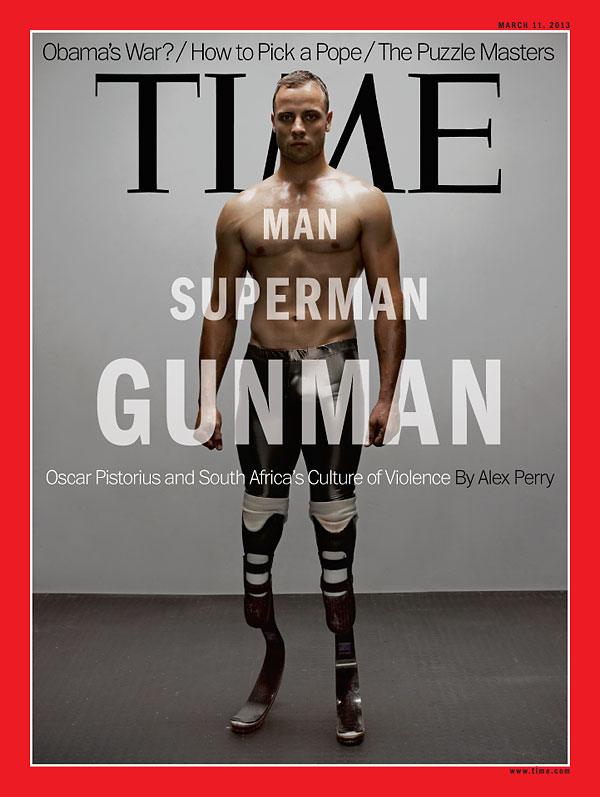

Pistorius was the latest incarnation of South African hope. He was born without a fibula in either leg, and both were amputated below the knee before he reached his first birthday. Using prosthetics, Pistorius went on to play able-bodied sports at Pretoria Boys High School, one of the country’s most prestigious private schools, before a knee injury left him on the sidelines. Advised to run for his recovery, he began clocking astonishing times using carbon-fiber blades that copied the action of a cheetah. In 2012 in London, he took two Paralympic gold medals and one silver and ran in an Olympic final and semifinal.

Pistorius credits his drive to his mother, who died at 42 when he was 15. He has the dates of her life tattooed in Roman numerals on his right arm, and by his account Sheila Pistorius did much to stamp the Afrikaner spirit of the devout, stubborn pioneer on her son. Just before the 11-month-old Pistorius underwent the operation to remove his lower legs, she wrote a letter for him to read when he was older. “The real loser is never the person who crosses the finishing line last,” she wrote. “The real loser is the person who sits on the side. The person who does not even try to compete.”

Pistorius has said he remembers Sheila, a working single mother who had divorced his father, shouting to her children as they got ready to leave the house, “Get your shoes! And Oscar, get your legs!” By giving him no special treatment or pity but showing no hint of underestimating him either, Sheila gave her son a belief not just that he was normal but also that he was special–divinely destined for the extraordinary. After he became an athlete, Pistorius chose a second tattoo for his left shoulder, the words of 1 Corinthians 9:26–27: “I do not run like a man running aimlessly.”

In a long battle with other athletes and sporting authorities, who argued that his prosthetics gave him an unfair advantage, he demanded to be treated like any other athlete–and succeeded as few ever had. Cool, handsome and impeccably dressed in appearances on magazine covers and billboards the world over, he forever altered perceptions of the disabled and even altered the word’s meaning–an ambition Pistorius encapsulated in his mantra: “You’re not disabled by the disabilities you have, you are able by the abilities you have.”

In South Africa, Pistorius’ achievements resonated deepest of all. In a nation obsessed by disadvantage, he was the ultimate meritocrat, a runner with no legs who ignored the accidents of his birth to compete against the best. Many South Africans no doubt would have seen his color before anything else. But for some, he existed, like Mandela, above and beyond South Africa’s divisions. He had outraced the past and symbolized a hoped-for future. “We adored him,” wrote the black commentator Justice Malala in Britain’s Guardian. “For us South Africans … it is impossible to watch Oscar Pistorius run without … wanting to break down and cry and shout with joy.”

With Pistorius’ arrest for Steenkamp’s murder, South Africa’s dreams collided with its reality. Pistorius doesn’t dispute that he killed Steenkamp. Rather he contends his action was reasonable in the circumstances.

The essence of Pistorius’ argument is unyielding defense of his laager. In an affidavit read in court by his lawyer, Barry Roux, Pistorius recalled how the couple spent Valentine’s eve quietly at his two-story home. “She was doing her yoga exercises and I was in bed watching television. My prosthetic legs were off.” Despite having dated only a few months, “we were deeply in love and I could not be happier.” After Steenkamp finished her exercises, she gave him a Valentine’s present that he promised not to open until the next day. Then the couple fell asleep in his second-floor bedroom.

Pistorius used to tell journalists that he never slept easy. In his affidavit, he said he was “acutely aware” of South Africa’s violent crime. “I have received death threats before. I have also been a victim of violence and of burglaries before. For that reason I kept my firearm, a 9-mm Parabellum, underneath my bed when I went to bed at night.”

Pistorius awoke in the early hours of Feb. 14. He remembered a fan he had left on his balcony and fetched it by hobbling on his stumps. Closing the sliding doors behind him, he “heard a noise in the bathroom … I felt a sense of terror rushing over me. There are no burglar bars across the bathroom window and I knew that contractors who worked at my house had left the ladders outside.”

“I grabbed my 9-mm pistol. I screamed for him/them to get out of my house … I knew I had to protect Reeva and myself … I fired shots at the toilet door and shouted to Reeva to phone the police. She did not respond and I moved backwards out of the bathroom, keeping my eyes on the bathroom entrance. Everything was pitch dark … When I reached the bed, I realized Reeva was not in bed. That is when it dawned on me that it could have been Reeva who was in the toilet.”

Pistorius says he put on his legs, beat down the locked door with a cricket bat, called an ambulance and carried Steenkamp downstairs to his front door, where he laid her on the floor. “She died in my arms,” he wrote.

Apartheid literally means separation. Nineteen years after Mandela and the ANC overthrew apartheid, South Africa still struggles with its divisions. What race divided, crime and distrust have now atomized. In a reverse of the U.S. experience, segregation has reached its logical end point: disintegration.

The dissolution is everywhere. Rival ANC leaders tear their party apart. Local politicians shoot each other in the street–40 assassinations in the past two years in President Jacob Zuma’s home state of KwaZulu-Natal alone. The wave of labor unrest that saw police shoot dead 34 miners at a Marikana platinum mine last August–and has held South Africa’s economy hostage ever since–has its origins in a power struggle between two unions. In the townships, South African blacks beat and kill Zimbabweans, Somalis and Congolese. In white areas, Afrikaner whites separate themselves from English whites, nursing a distrust that dates from the 1899–1902 Boer War.

In the first years after apartheid, Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke about a “rainbow nation.” The new South Africa has turned out to be no harmonious band of colors. Behind the latest in intruder deterrents for the elite, or flimsy barriers pulled together from tin sheets and driftwood for the poor, South Africans live apart and, ultimately, alone.

Despite the adulation he received, that isolation seemed to have touched Pistorius. He sometimes seemed out of step. At his bail hearing, Steenkamp’s best friend, Samantha Greyvenstein, said Steenkamp told her “sometimes … Oscar was moving a little fast.” Likewise, Steenkamp’s housemate has told journalists that Pistorius was a persistent suitor to the point of harassment. In his summation, prosecutor Gerrie Nel noted that Pistorius once persuaded a friend to take the blame for firing a gun in a restaurant. “‘Always me,'” said Nel. “‘Protect me.'”

It takes a collective effort to stop a country from falling apart. Fragmented and behind their barricades, individual South Africans just get to watch. just another south african story was the weary headline over a picture of Pistorius and Steenkamp in the iMaverick, a South African online magazine. Indeed, the media attention directed at the Pistorius case unearthed so many similar South African stories, it began to seem that almost no one connected to it was untouched by violent death. On Feb. 21 came news of Detective Warrant Officer Botha’s seven attempted-murder charges. On Feb. 24, reports emerged that Pistorius’ brother Carl faces trial for culpable homicide over a 2008 road accident in which a woman motorcyclist died. That same day a first cousin of Magistrate Desmond Nair, who is presiding in the case, killed herself and her sons, ages 17 and 12, with poison at their home in Johannesburg.

There is a moral to these South African stories. A nation whose racial reconciliation is even today hailed as an example to the world is, in reality, ever more dangerously splintered by crime. And inside this national disintegration, however small and well-defended South Africans make their laagers, it’s never enough. Father rapes daughter. Mother poisons sons. Icon shoots cover girl.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com