On November 5, 1990, an Arab gunman assassinated Rabbi Meir Kahane during a speech at Marriot Hotel in New York City. My mother woke me up the minute she saw the breaking news on TV, and we fled the house in a terrified daze. I was 7 years old at the time—a shy, chubby New Jersey kid in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle pajamas. The gunman was my father.

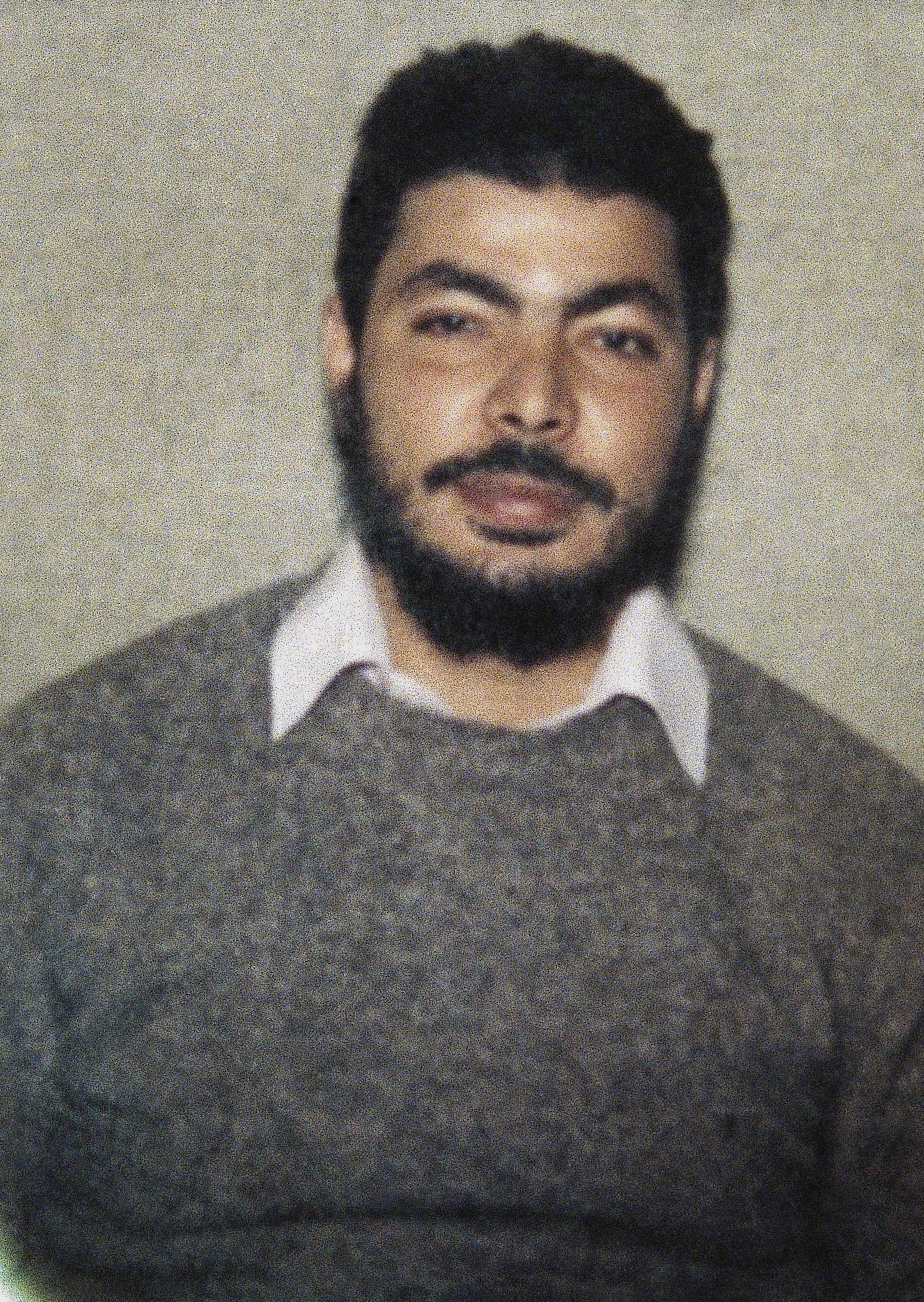

My father’s despicable act decimated my family. It tipped us into a life of death threats and media harassment, nomadic living and constant poverty. Kahane had been a pro-Israel militant and the founder of the Jewish Defense League. When he killed him, my father, El-Sayyid Nosair, became the first known Islamic jihadist to take a life on American soil. He worked with the support of a terror cell overseas that would ultimately call itself al-Qaeda. And his career as a terrorist was not yet over.

In 1993, from his prison cell at Attica, my father helped plan the first bombing of the World Trade Center with some old associates from a Jersey City mosque, including Omar Abdel-Rahman, whom the media dubbed “the Blind Sheikh.” Their horrible hope was that one tower would knock over the other and the death toll would be stratospheric. They had to settle for a blast that tore a hole 100 feet wide through four levels of concrete, the injury of more than a thousand innocents, and the deaths of six people, one of them a woman seven months pregnant.

The fact that my father went to prison when I was 7 just about ruined my life. But it also my made my life possible. He could not fill me with hate from jail. And, more than that, he could not stop me from coming into contact with the sorts of people he demonized and discovering that they were human beings—people I could care about and who could care about me. Bigotry cannot survive experience. My body rejected it.

When I was 18 and had finally seen a little bit of the world, I told my mom I could no longer judge people based on what they were—Muslim, Jewish, Christian, gay, straight—and that starting right then and there I was only going to judge them based on who they were. She listened, she nodded and she had the wisdom to speak the six most empowering words I have ever heard: “I’m so tired of hating people.”

She had good reason to be tired. Our journey had been harder on her than anyone else. For a time, she took to wearing not only the hijab that hid her hair, but also the veil called the niqab that cloaked everything but her eyes: She was a devout Muslim and she was afraid she’d be recognized.

My father is now in the United States penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, having been sentenced to life plus 15. I have not visited him in 20 years. Every so often, I’ll get an e-mail from the prison saying that he would like to initiate correspondence. But I’ve learned that even that leads nowhere good. He lied to us for so many years about what he’d done that one time I e-mailed him and asked, flat-out, whether he murdered the rabbi and plotted to attack the World Trade Center. I told him, I’m your son and I need to hear it from you. He answered me with an indecipherable, high-flown metaphor. It made him seem desperate, grasping—and guilty.

One of the many upsides to not speaking to my father anymore is that I’ve never had to listen to him pontificate about the vile events that took place on September 11th. He must have regarded the destruction of the Twin Towers as a great victory for Islam—maybe even as the culmination of the work he and the Blind Sheikh began years earlier.

For what it’s worth—and I’m not sure what it is worth at this point–my father now claims to support a peaceful solution in the Middle East. He also claims to abhor the killing of innocents, and he admonishes jihadists to think of their families. He said all this in an interview with the Los Angeles Times last year. I hope his change of heart is genuine, though it comes too late for the innocents that he himself helped murder. I don’t pretend to know what my father believes anymore. I just know that I spent too many years caring.

As for me, I’m no longer a Muslim and I no longer believe in God. It broke my mother’s heart when I told her, which, in turn, broke mine. My mother’s world is held together by her faith in Allah. What defines my world is love for my family and friends, the moral conviction that we must all be better to one another and to the generations that will come after us, and the desire to undo some of the damage my father has done in whatever small ways I can. I am convinced that empathy is stronger than hate, and that our lives should be dedicated to making it go viral.

Zak Ebrahim was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on March 24, 1983, the son of an Egyptian industrial engineer and an American schoolteacher. He dedicates his life to speaking out against terrorism and spreading his message of peace and nonviolence. Jeff Giles has written for The New York Times Book Review, Rolling Stone, and Newsweek, and has been a top editor at Entertainment Weekly. His first novel for young adults will be published by Bloomsbury in 2016. From The Terrorist’s Son: A Story of Choice by Zak Ebrahim and Jeff Giles. Copyright © 2014 by Zak Ebrahim and Jeff Giles. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com