Police psychologist Georg Sieber imagined 26 ways the 1972 Summer Olympics could go terribly wrong. Commissioned by organizers to predict worst-case scenarios for the Munich games, Sieber came up with a range of possibilities, from explosions to plane crashes, for which security teams should be prepared.

Situation Number 21 was eerily prescient, as TIME would describe many years later. Sieber envisioned that “a dozen armed Palestinians would scale the perimeter fence of the [Olympic] Village. They would invade the building that housed the Israeli delegation, kill a hostage or two (“To enforce discipline,” Sieber says today), then demand the release of prisoners held in Israeli jails and a plane to fly to some Arab capital.” The West German organizers balked, asking Sieber to downsize his projections from cataclysmic to merely disorderly — from worst-case to simply bad-case scenarios. Situations such as Number 21 could only be prevented by scrapping the Olympics entirely, they argued. Instead of beefing up security, they scaled back their expectations of threat.

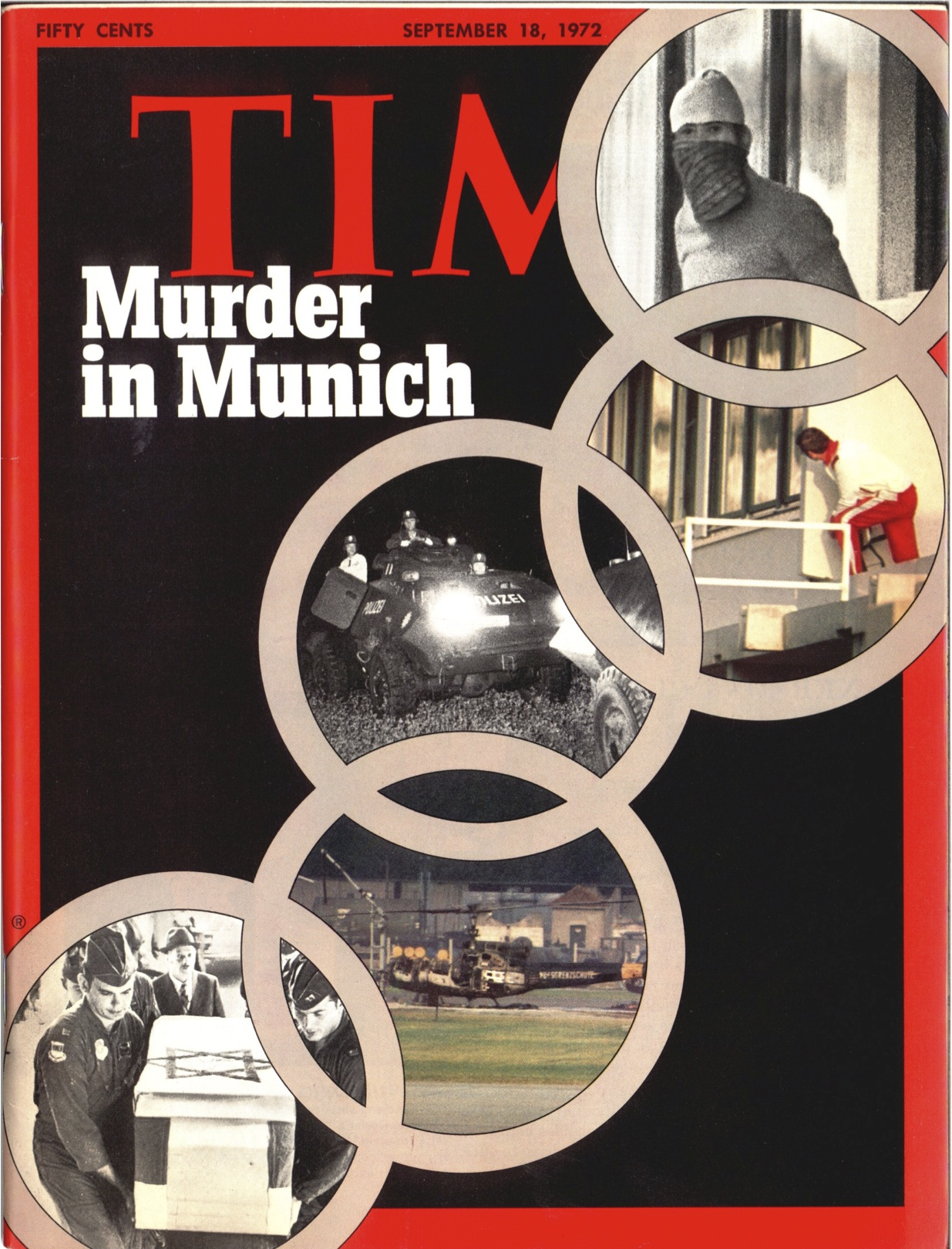

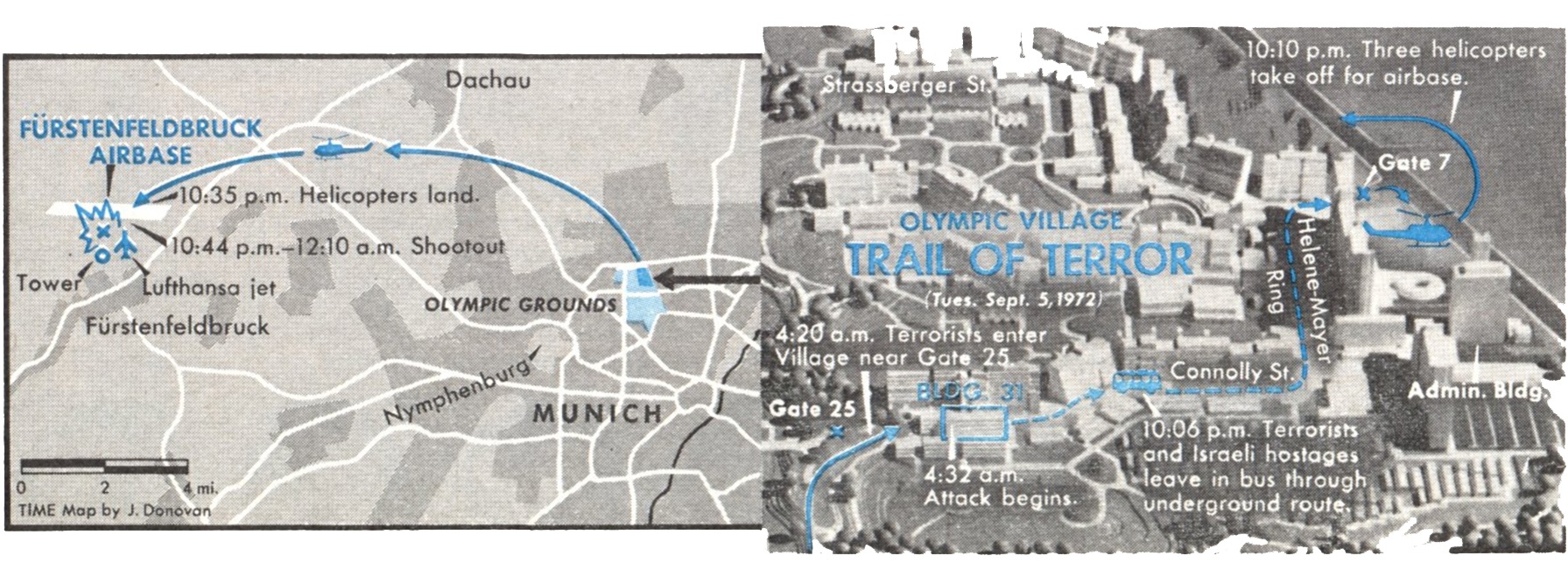

So they were unprepared when, early this morning in 1972, an attack unfolded almost exactly according to Sieber’s hypothetical specifications. Eight men affiliated with the Palestinian terrorist group Black September broke into the Israeli apartment before dawn and took 11 athletes and coaches hostage.

Thanks to lax security — exposed decades later when a classified report was made public in 2005 — it was a relatively easy task for the terrorists. They were seen scaling the fence, but, wearing tracksuits, were taken for athletes and ignored. Getting into the Israelis’ housing was even easier: Among other departures from Sieber’s recommendations, the team had been assigned rooms on the ground floor. Once inside, the terrorists killed two hostages almost immediately and demanded the release of 234 prisoners from Israeli jails in exchange for the rest. While the world watched, West German officials launched into poorly planned, ineffectual action. First, they dismissed Sieber, telling him his services were no longer needed. Then they botched a rescue mission that culminated in the deaths of all the remaining hostages, a German officer and five of the eight commandos. The three who survived were captured but later released in exchange for a hijacked Lufthansa plane.

The tragedy was also devastating to the Germans, who had hoped that being gracious Olympic hosts would distract from the memory of Nazi propaganda at their last games, the Berlin Olympics in 1936. They had given the 1972 Olympics the official motto Die Heiteren Spiele, which translates variously as the happy games, the cheerful games or the carefree games. That phrase presented a stark contrast to reality — and a grim reminder that merely hoping for the best will not prevent the worst.

Read TIME’s Sept. 18, 1972, cover story about the attack: Horror and Death at the Olympics

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com