It was 225 years ago today that the still-nascent United States finally decided to get its financial house in order. The Department of the Treasury was established on Sept. 2, 1789, during an early session of the 1st United States Congress. The Department’s duties, according to the founding law, are:

“…to digest and prepare plans for the improvement and management of the revenue…to prepare and report estimates of the public revenue, and the public expenditures; to superintend the collection of revenue; to decide on the forms of keeping and stating accounts and making returns, and to grant under the limitations herein established, or to be hereafter provided, all warrants for monies to be issued from the Treasury, in pursuance of appropriations by law.”

Or, in layman’s terms, the Treasury Department issues savings bonds, prints cash, mints coins, collects taxes through the IRS and enforces laws related to alcohol and tobacco. People often conflate the duties of the Treasury with those of the Federal Reserve, but the two are actually separate organizations. The Treasury is a department of the executive branch and is generally concerned with properly maintaining the day-to-day activities of the government. The Federal Reserve is an independent body that sets long-term fiscal policy in an effort to control borrowing and inflation rates.

Our first Secretary of the Treasury was Alexander Hamilton, a key figure in the development of early American fiscal policy who advocated heavily for a central banking system and the federal assumption of state debts following the Revolutionary War (and no, he didn’t put himself on the $10 bill — he wasn’t added to the currency until the 1920s). The current secretary is Jack Lew, appointed by President Obama in 2013.

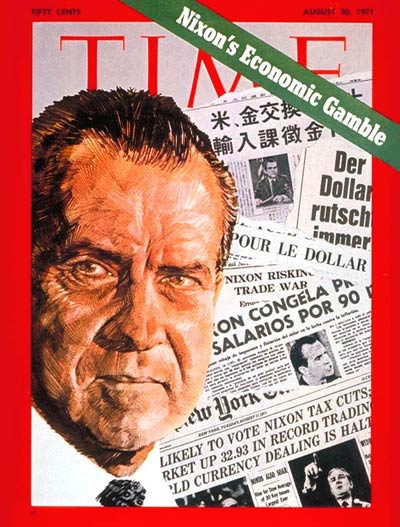

In addition to the Treasury’s birthday, we also just passed another significant fiscal anniversary. In August 1971, the U.S. stopped converting dollars held by foreign governments to gold at a value of $35 per ounce. The policy, called the Bretton Woods system, had been put in place following World War II to convince rebuilding countries like Germany and Japan to invest in American dollars. But by the 1960s, the system was placing strain on the U.S. economy as the number of dollars held by foreign countries outpaced the amount of gold the U.S. had on hand. Following a secret meeting at Camp David with this top advisers, President Richard Nixon announced on August 15 a suspension of the policy, transforming the dollar into a floating currency not pegged to any particular exchange rate. Nixon also announced a 90-day freeze on prices and wages in the U.S. and an additional 10% tariff on imports.

Collectively known as the “Nixon Shock,” the measures surprised people both at home and abroad. Reporting in the days following the announcement, TIME wrote of foreign leaders abandoning their summer vacations to react to the announcement amid worries that the dollar, no longer tied to a fixed rate, would plummet in value. In the years that followed, countries in Europe and Asia also allowed their currencies to float, making exchange rates more volatile than they had been in the past.

Read TIME’s original 1971 report on Nixon’s controversial decision to abandon gold: The Dollar: A Power Play Unfolds

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com