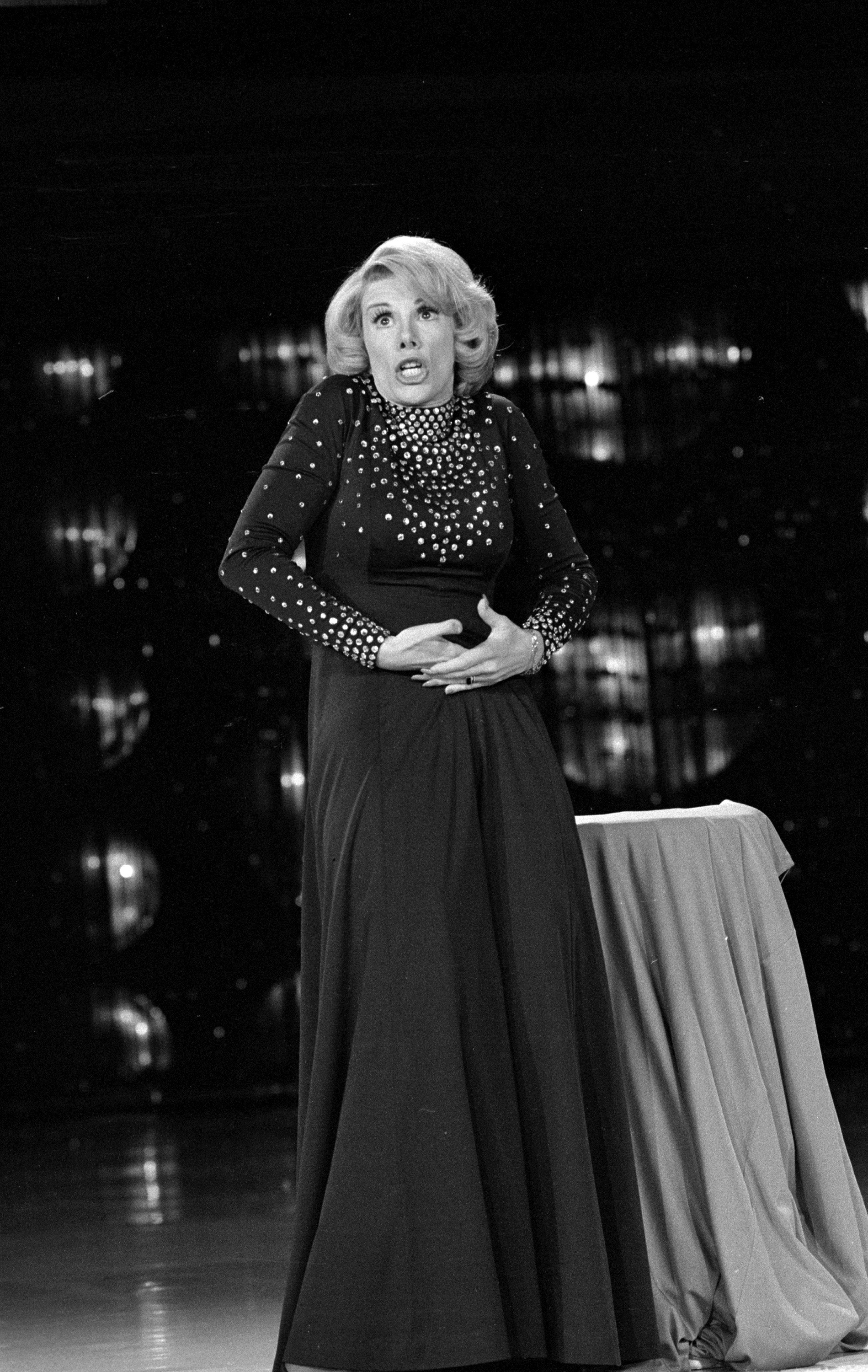

“Can we talk?” Joan Rivers always asked audiences, and by this she meant: Can I talk about life’s biases and prejudices — mine? For more than a half-century, first as a pioneering standup comedienne, then as a defiant survivor, she spoke skewed truth to power, and in doing so became her own potentate and garishly fossilized icon. She could be a ranting bag lady, if the lady were as funny as she was rude, and the bag from Gucci.

Rivers, who died Sept. 4 at 81 in New York City after complications from throat surgery, created her look and legend as much as did Santa Monica plastic surgeon Steven Hoefflin (who also was Michael Jackson’s nose-whittler). She made fun of herself — her homeliness as a child, her flat chest, those layers of cosmetic archaeology (“When I die they will donate my body to Tupperware”) — and everyone else from Bo Derek to Tom Cruise. “I succeeded,” she said, “by saying what everyone else is thinking.” Everyone else, that is, with a wicked mind and an agile tongue.

Born Joan Alexandra Molinsky in Brooklyn, she graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Barnard College in 1954. (“I spit on education. No man will ever put his hand up your dress looking for a library card.”) In 1959 she acted in the off-Broadway play Driftwood opposite another budding, brassy dominatrix, the 16-year-old Barbra Streisand. But nobody could write for Joan better than she, or manufacture a comedic personality so etched in acid and agita. Transporting the bold delivery of such earlier standup femmes as Sally Marr (Lenny Bruce’s mother) and Belle Barth to the same night clubs that nurtured the young Woody Allen, Molinsky changed her name on the advice of her then-manager, whose name was Tony Rivers.

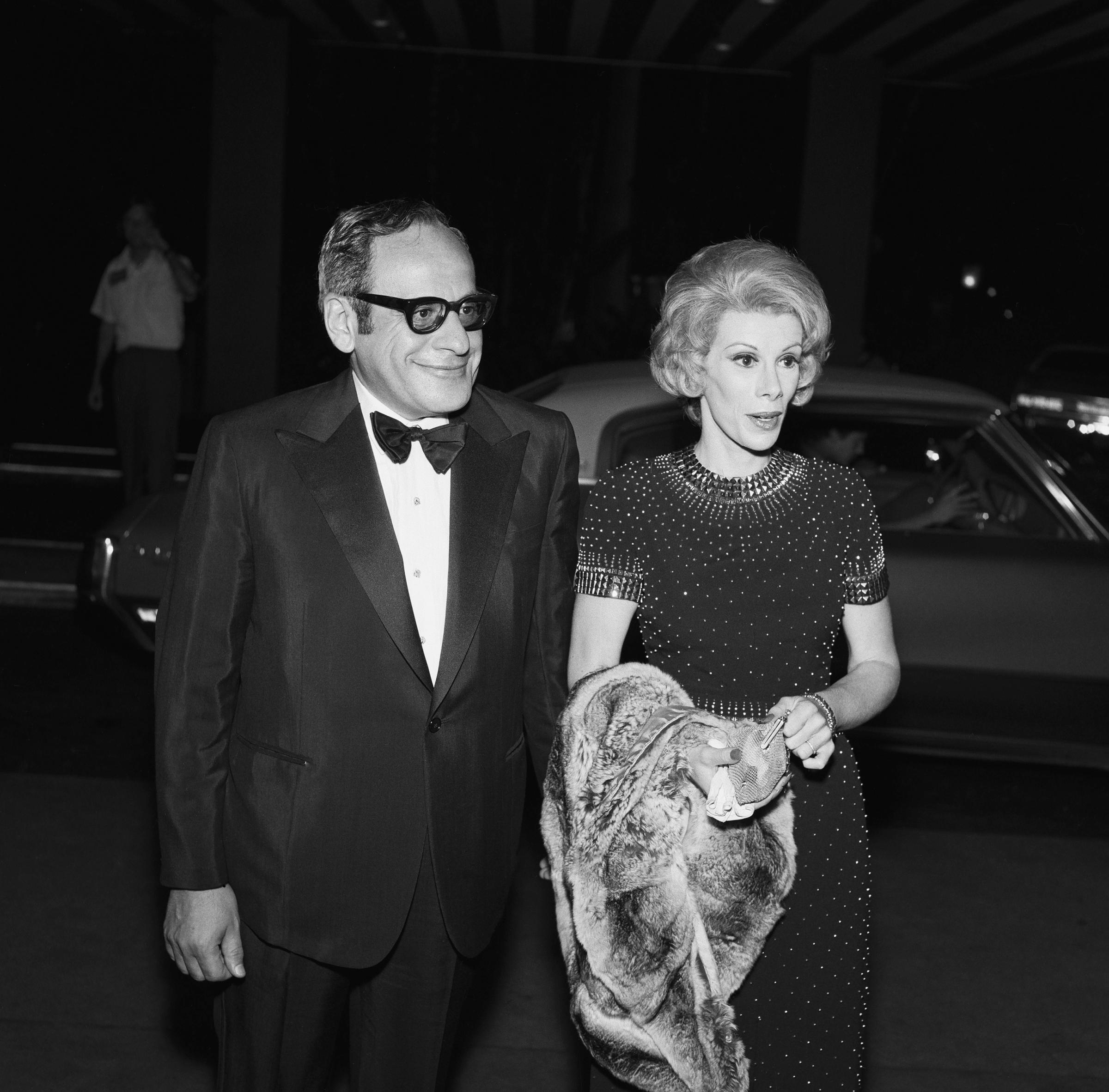

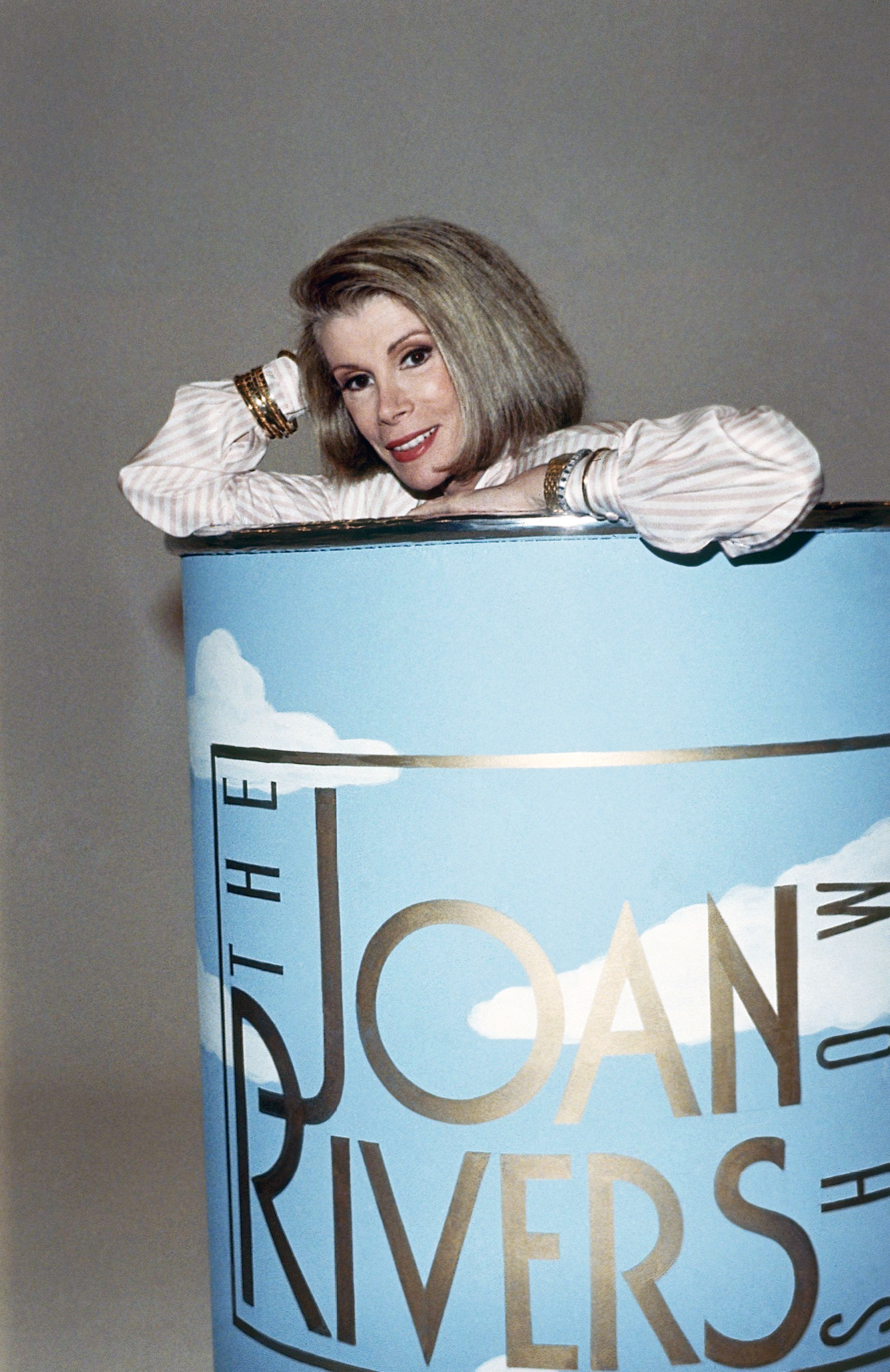

She got her big break on Feb. 17, 1965, when she first appeared with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. In 1983 Carson named Rivers his “permanent guest host”; but permanent proved ephemeral, as she fled to the newborn Fox network in 1986 for a late-night show opposite his. She didn’t tell Carson in advance, and he never spoke to her again. A year later, Rivers’ husband and longtime manager Edgar Rosenbaum killed himself by taking an overdose of prescription drugs. Even this tragedy became fodder for her act. “I was the one who really caused Edgar’s suicide,” she would say, “because, while we were making love, I took the bag off my head.”

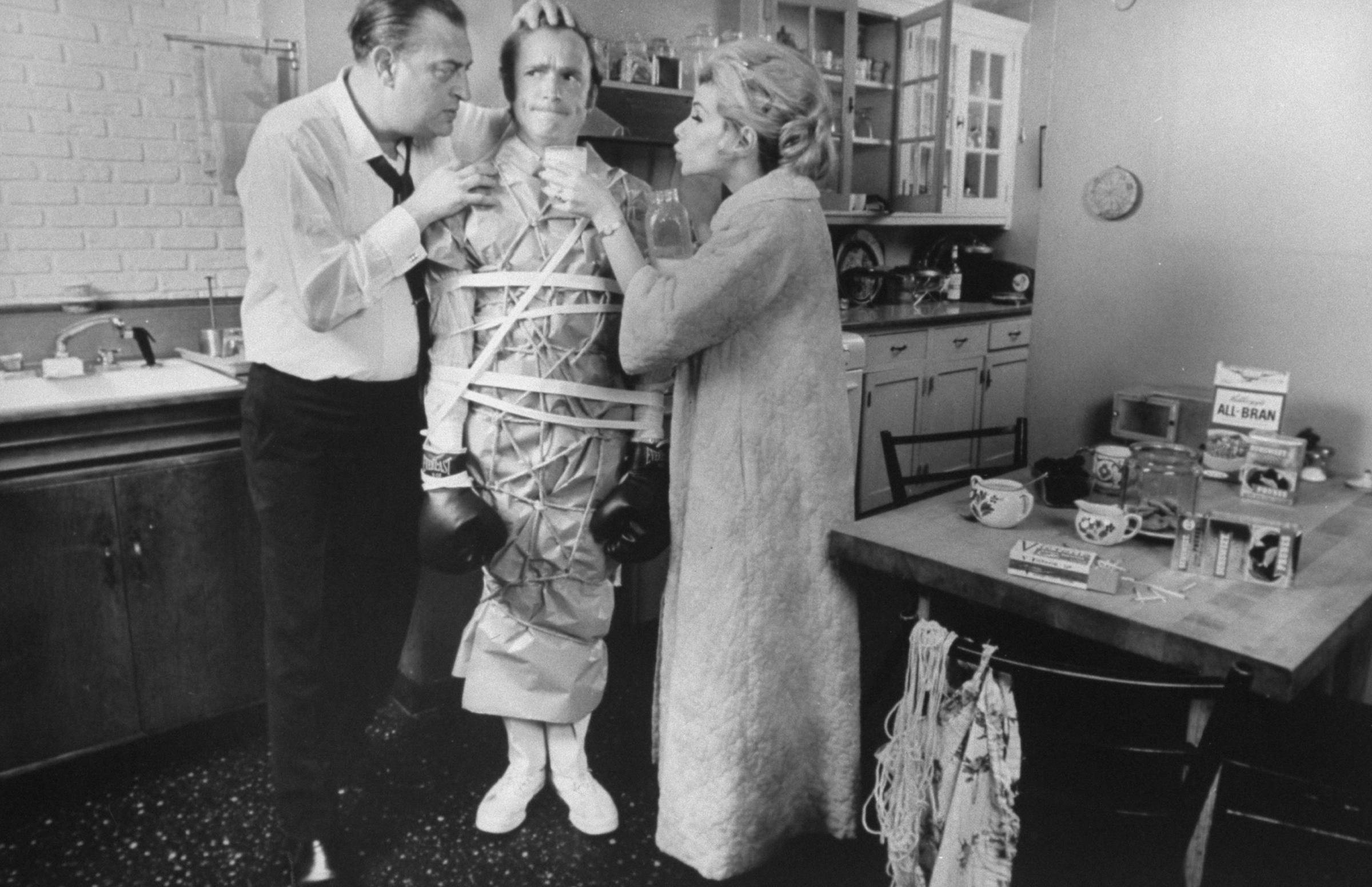

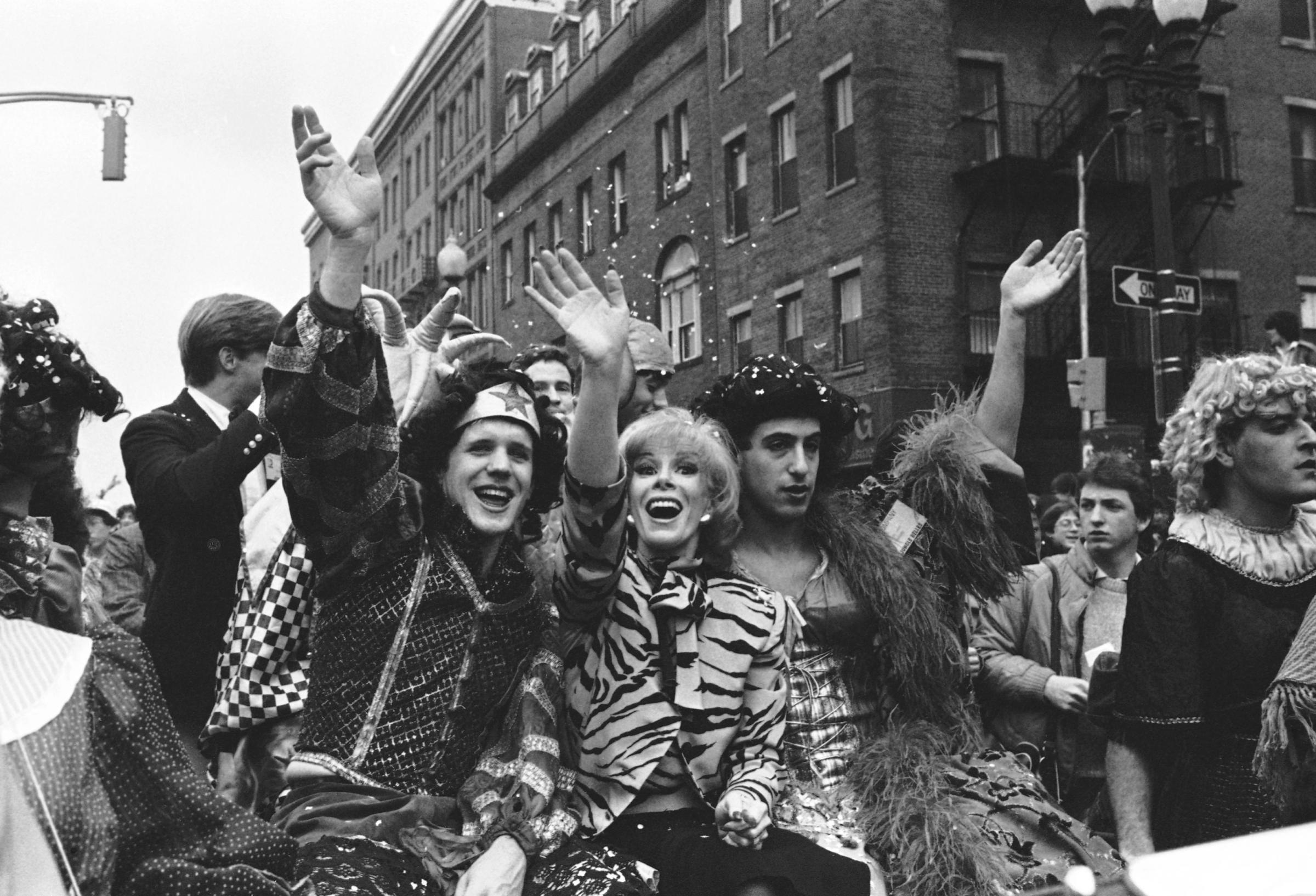

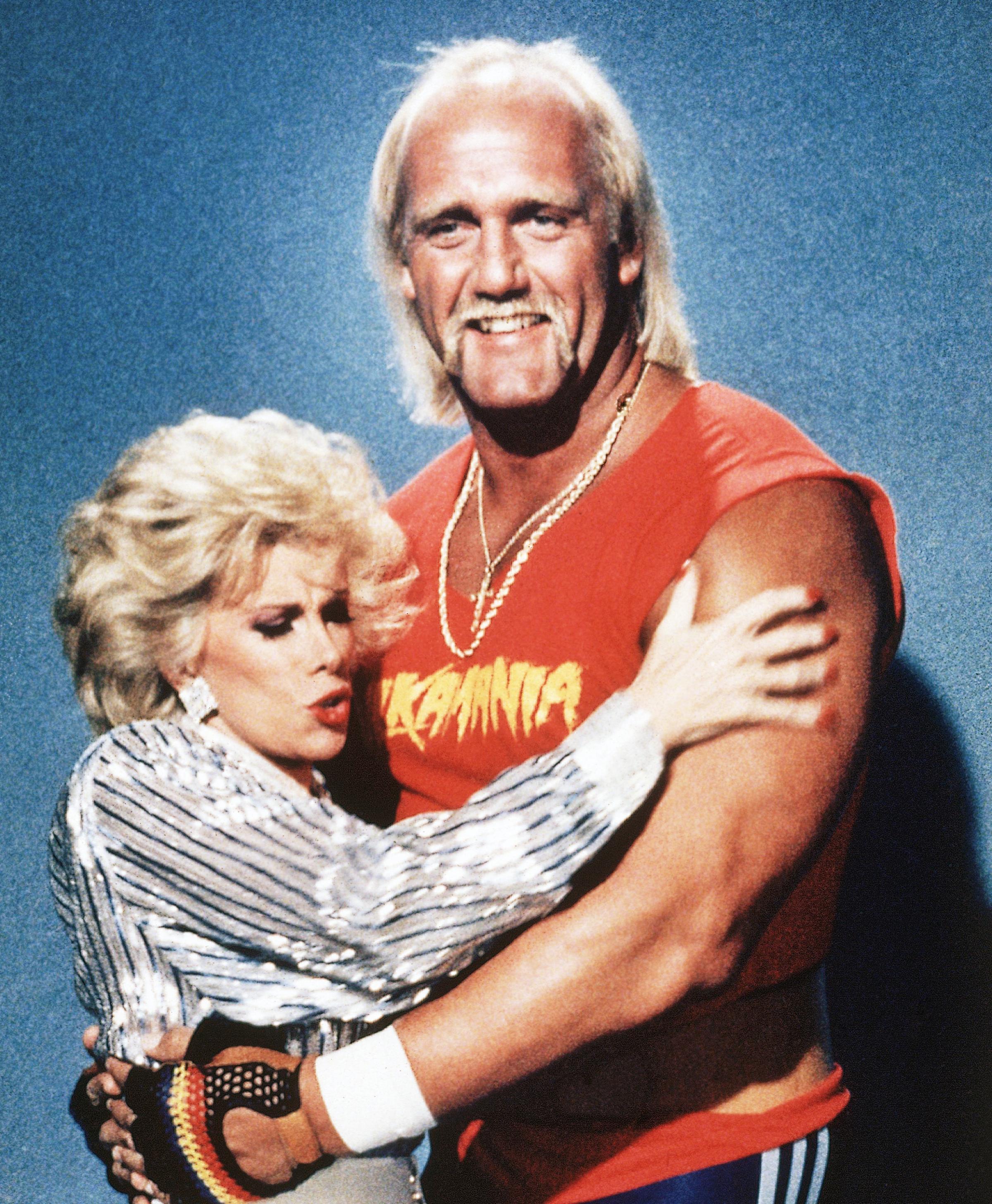

Rivers starred in and cowrote two Broadway plays: Fun City, which expired after a week in 1972, and Sally Marr…and Her Escorts, which ran for 50 performances in 1994 and earned her a Best-Actress Tony nomination. She also directed and cowrote the 1978 movie Rabbit Test, with Billy Crystal as the world’s first pregnant man. But narrative fiction was not her forte, unless it was the tragicomic saga of her own life — and of her randy alter-ego Heidi Abramowitz— which she alchemized out as a talk-show stalwart, a QVC pitchwoman (“The only time a woman has a true orgasm is when she is shopping”), an indefatigable diva on the road and a red-carpet scourge on showbiz awards nights with her daughter Melissa.

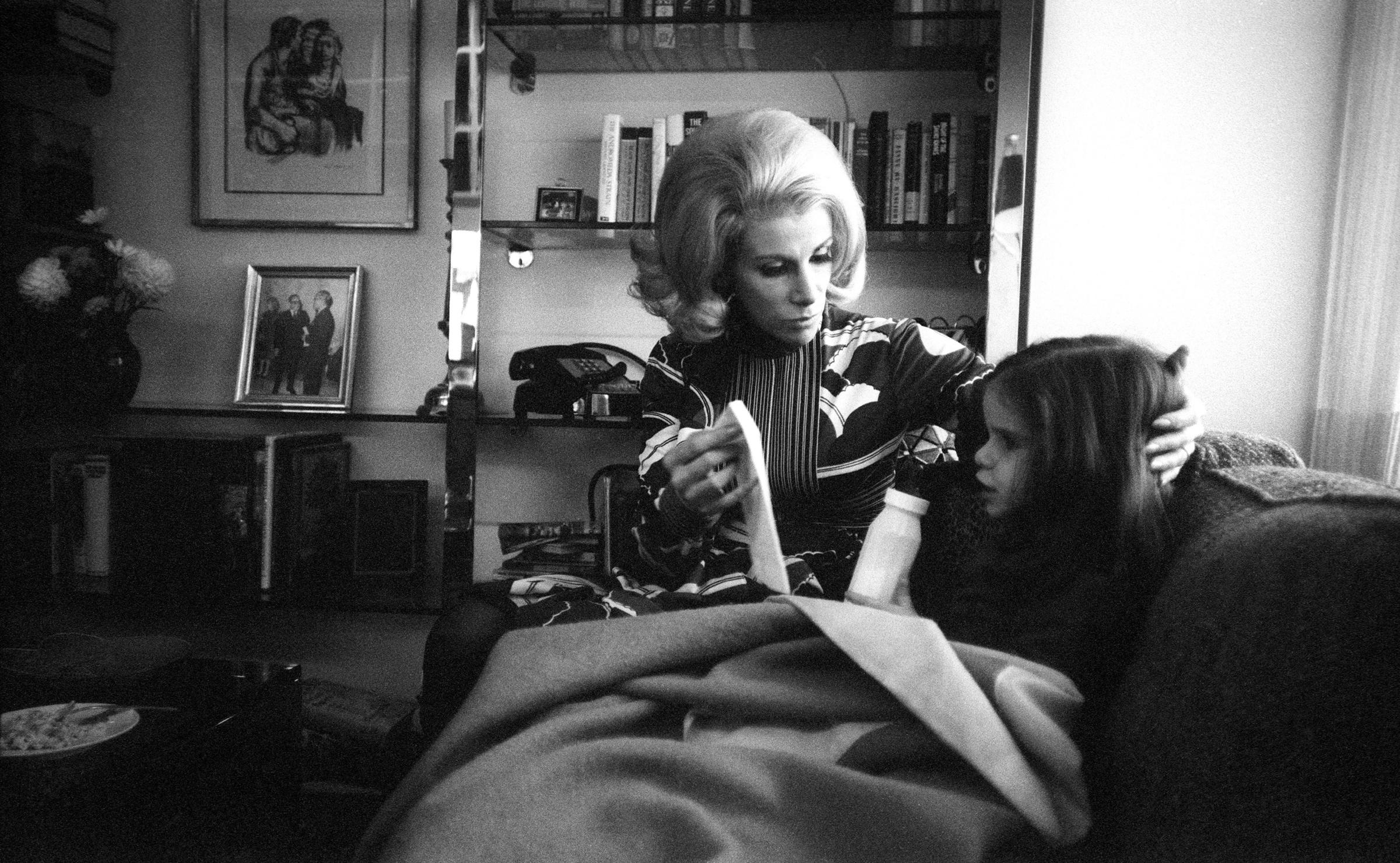

In the 2010 documentary Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work, Melissa says that her mother’s career “was like me having a sister.” Having Joan for a mother meant being the butt of her jokes (“She doesn’t want me to be lonely; isn’t that nice? She’s trying to fix me up with Robert Blake”), competing with her on Donald Trump’s Celebrity Apprentice (Joan won, Melissa was fired early) and sharing the screen with Mom in a 2010 Bravo caper called Joan Rivers: Before Melissa Pulls the Plug. A perpetual commotion machine, Joan had to keep working. In A Piece of Work, her assistant says, “Joan turns down nothing.” For Rivers, fear was an engagement calendar with no gigs. The woman who turned hate and self-hatred into comedy needed the loving validation of an audience — any audience.

As she careered into her Golden Girls years, she mocked the Grim Reaper by saying that “age-appropriate” clothing “would be a shroud” and that, “At my age, an affair of the heart is a bypass.” Rather less amusingly, she discounted the deaths of several thousand Palestinians in this year’s war with Israel by fuming, “They started it. We now don’t count who’s dead. You’re dead. You deserve to be dead.” She added: “They were told to get out. They didn’t get out. You don’t get out, you are an idiot. At least the ones that were killed were the ones with low IQs.” She later said her remarks were taken out of context.

Then again, life and career were dead-serious to Rivers, for whom every challenger, including the younger female comics, deserved to be whupped in a cage match. “They all come up to me and say, ‘Without you, I couldn’t be here, the barriers you broke down.’ I say, ‘Get the f— away from me. I still could take every one of you with one hand behind my back. Outta here. Talk like that at my funeral, but not till then.’”

Let the eulogies from her admirers and victims begin now. Let them speak of her caustic wit, her acute timing and her understanding that comedy at its sharpest is not an anesthetic but a defibrillator. If Joan Rivers can no longer talk, she deserves to be talked about forever.

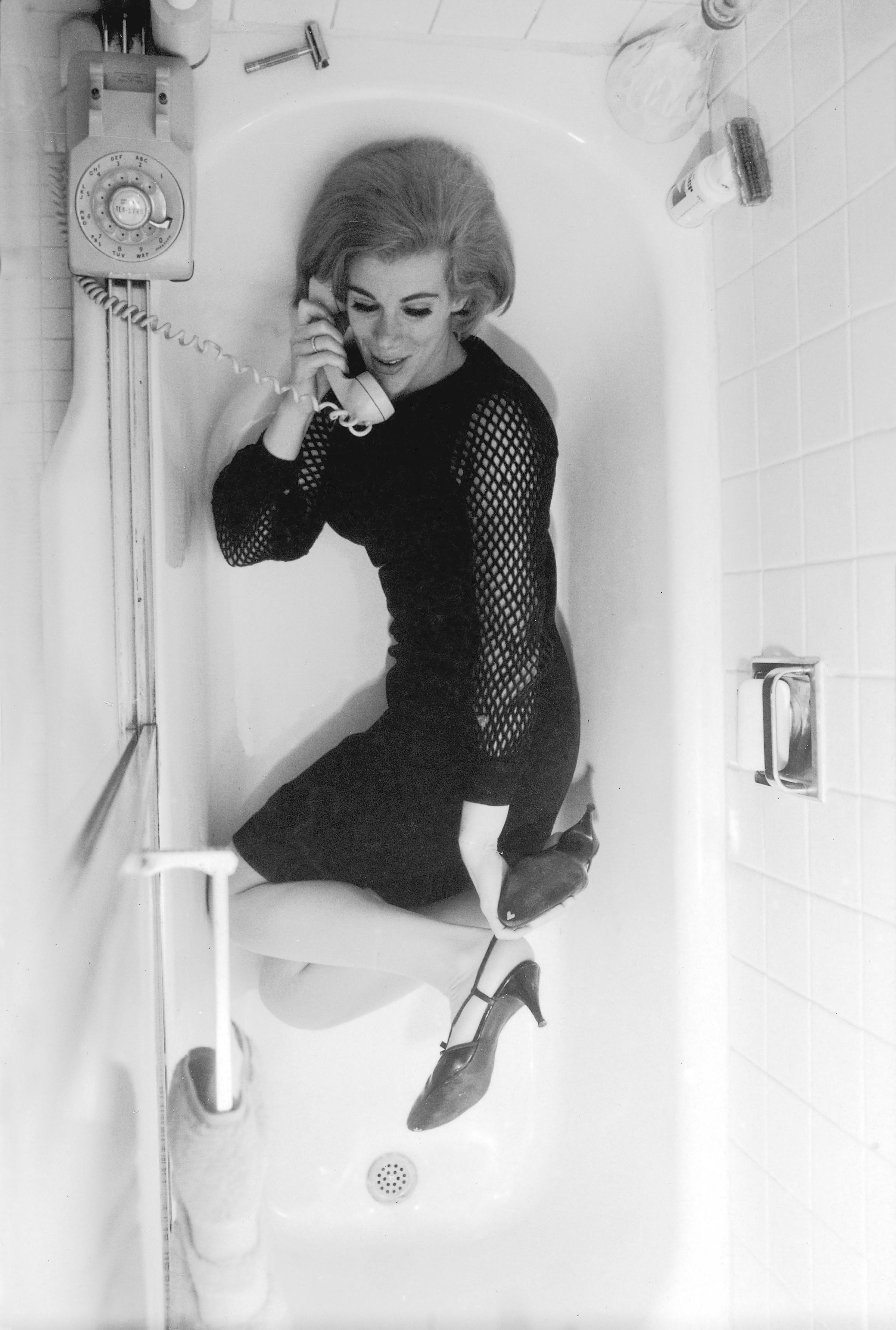

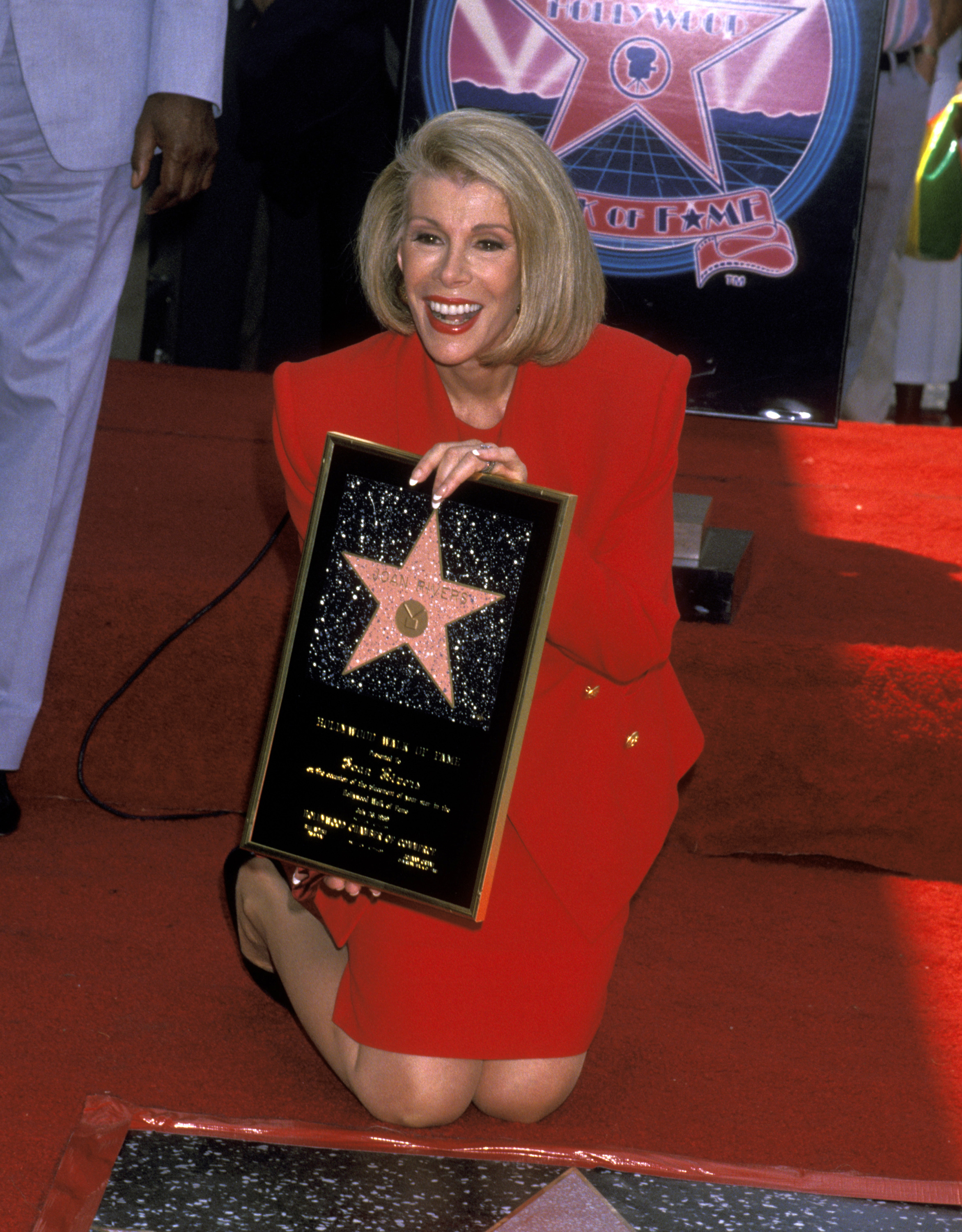

Joan Rivers: A Life of Laughter in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com